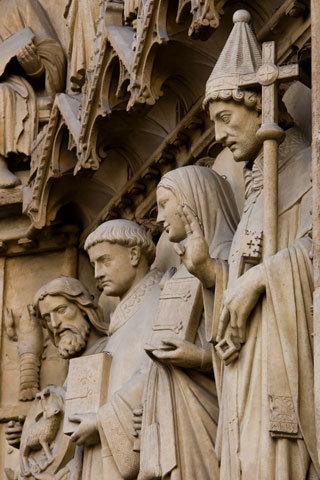

Saints adorn the Portal of the Virgin at Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris. (Dreamstime)

On Sunday, two popes, John XXIII and John Paul II, will join the ranks of formally canonized saints of the Catholic church. In doing so, they will bring the number of popes who have been officially recognized as saints to 80 (out of some 263 popes who have been in office, according to traditional lists).

At first glance, this seems like a very high number, but it's worth remembering that the vast majority of these individuals date from the earliest centuries of the church. The first 35 bishops of Rome are all regarded as saints, as are 52 out of the first 54. In the case of many of these early popes, little historically reliable information is available for their lives. (How many have heard of the second-century pope Telesphorus, for instance? Or his successor, Hyginus?)

What is clear is that many of these early popes lived in an age of martyrs, and their sainthood was closely associated with their martyrdom. Also, for much of the first millennium of the church's history, canonizations were not made by popes. Rather, saints were recognized by popular acclamation at a local level and (when things ran smoothly) under the supervision of the local bishop.

The first evidence we have for a pope canonizing an individual dates from as late as 993. By 1234, Pope Gregory IX had declared that no person could legitimately be canonized without the authority of the pope. Over time, there evolved a complex legal process of assessing the merits of candidates for sainthood, the requirement of a set number of miracles (up to four at one stage), and an intense scrutiny of the person's life. This scrutiny was carried out by an official called the "promoter of the faith" (better known as the "devil's advocate"), and it was up to those championing an individual's cause to prove that their candidate was not a charlatan or a scoundrel.

One might have expected that in the wake of an age of increasing papal centralization of power, many more papal canonizations would follow -- especially since a curious document from 1075 purportedly compiled by Pope Gregory VII (1073-85) rather audaciously declared that every pope, legitimately ordained, is made a saint through the merits of St. Peter. But this has not been the case. The irony is that since Gregory VII's pontificate, there have been only four: Gregory VII himself (canonized in 1606), Celestine V (canonized in 1313), Pius V (canonized in 1712), and Pius X (canonized in 1954). This makes the double canonization of John XXIII and John Paul II quite a rare event.

But what does it mean to be declared a saint in any case? Undoubtedly, models of sainthood have evolved and developed over the centuries. In the New Testament, Paul uses the term hagios ("holy one") quite liberally to refer to the members of the Christian community at large who are "called to be saints" (Romans 1:7). The earliest veneration of saints centered on the tombs of martyrs over which the Eucharist was celebrated. The bones and other remains became important relics that possessed miraculous properties owing to their merits.

By the fourth century, when the Roman Empire's persecution of Christians ceased, opportunities for martyrdom evaporated and new forms of imitating Christ began to emerge. Individuals such as St. Antony of the Desert renounced everything and fled to remote regions to pursue lives of asceticism (literally "training" or "discipline"), which involved long hours of prayer, penance and fasting. They came to be regarded as "daily martyrs." A fourth-century biography of Antony by Bishop Athanasius of Alexandria was hugely influential in creating an enduring model of sanctity. Other works followed, such as Sulpicius Severus' Life of Martin of Tours, which became a "best-seller" in the West.

The ideal of asceticism would continue to play a major role in many of the lives of saints up to the modern period (for example, Sts. John Vianney and Padre Pio of Pietrelcina). It is noteworthy, for instance, that in his 2010 book Why He Is a Saint, Msgr. Slawomir Oder, promoter of John Paul II's cause for canonization, included the pope's practice of mortification by self-flagellation and lying prostrate through the night on a bare floor as further proof of his sanctity.

It would be misleading, however, to claim that the early saints were merely regarded as great practitioners of penance and workers of miracles. They were also models of Christian charity. The story of how Martin of Tours divided his cloak in two to give half to a beggar (later identified as Christ) is a case in point. One of the primary functions of written lives of saints, in fact, was to instil virtue in those who heard them. (The very word legenda, or "legend," a term used for these lives, implies that these stories were to be read -- often, aloud -- to the faithful.)

For centuries, it would be the lives of saints, as recorded in written works and on the stained glass windows of parish churches, that would instruct generations of Catholics in the art of imitatio Christi, how to imitate Christ. The example of their virtuous lives and, sometimes, heroic sacrifices would often have a greater catechetical impact on lay men and women than many volumes of more formal Christian doctrine. Little wonder then that Irish Jesuit theologian George Tyrrell (1861-1909), regarded the saints and not the theologians as the real teachers of the church.

Despite their impact on popular Catholicism over the centuries, the pool from which formally canonized saints have been drawn has until recently been quite small. Scholars estimate that men outnumbered women by four to one, and that most of these were members of religious orders. Laypeople were largely underrepresented and those that were canonized almost exclusively came from aristocratic or otherwise wealthy backgrounds. A rare exception was Isidore the Farmer (died 1130), whose cause was successfully promoted by King Philip III in the 17th century. There were also huge geographical disparities, with some lands having no local saint recognized by the universal church. But this situation would change dramatically with the pontificate of John Paul II.

In many respects, both John XXIII and John Paul II have a share in this widening of the categories of sainthood. The former will always be remembered as the pope -- and now "saint" -- of the Second Vatican Council. When John XXIII was beatified in the year 2000, John Paul II fittingly assigned Oct. 11 (the date of the opening of the Second Vatican Council) as his feast day. This was the council at which "all the faithful of Christ, of whatever rank or status" were called to universal holiness (Lumen Gentium). In St. Paul's words once again, they were "called to be saints."

John XXIII did not live long enough to canonize many saints (there were eight in all, including, most famously, St. Martin de Porres), but John Paul II would more than make up for this. From the years 1000 to 1978, fewer than 1,000 individuals were canonized. In John Paul's 26 years in office, he canonized 482 saints, almost 250 of whom were laypeople. In his saint-making, John Paul cast a wide net, both vocationally and geographically. Here was a man who took the words of Lumen Gentium seriously. More than one commentator has since noted the significance of the fact that John Paul II was ordained, as a young man, on the feast of All Saints.

The creation of saints can also be a powerful statement of a pope's priorities. As a former diplomat in Bulgaria, Greece and Turkey, John XXIII, in his canonizations, clearly appreciated St. Gregory Barbarigo (1625-97) and his work for the unity of the Latin and Orthodox churches, something that was close to this pope's heart; likewise St. Vincent Pallotti's call in 1836 for the octave of the Epiphany to be observed for the reunion of the Eastern and Western churches.

John Paul II also highlighted what he regarded as special virtues in his saints. Gianna Beretta Molla, who died in 1962 while carrying a difficult pregnancy to term rather than opting for an abortion, is one such case. She was canonized in 2004. In 1990, John Paul would beatify Pier Giorgio Frassati (1901-25) a young lay activist who lived out Catholic social teaching in an "explosion of joy." A saint for the modern world, he enjoyed hiking, mountain climbing, skiing, and attending the theater and art galleries. In beatifying individuals such as Frassati, John Paul II clearly wished to highlight the ordinariness of extraordinary sanctity. This trend continued under Pope Benedict XVI in his 2010 beatification of Chiara Badano, a keen tennis player, hiker and swimmer.

There can be little doubt that the call to sanctity has been released from the confines of the cloister for good. It is fitting that two of the architects of this development will now be counted among those holy men and women who have gone before them.

[Salvador Ryan is a professor of ecclesiastical history at St. Patrick's College, Maynooth, in County Kildare, Ireland.]