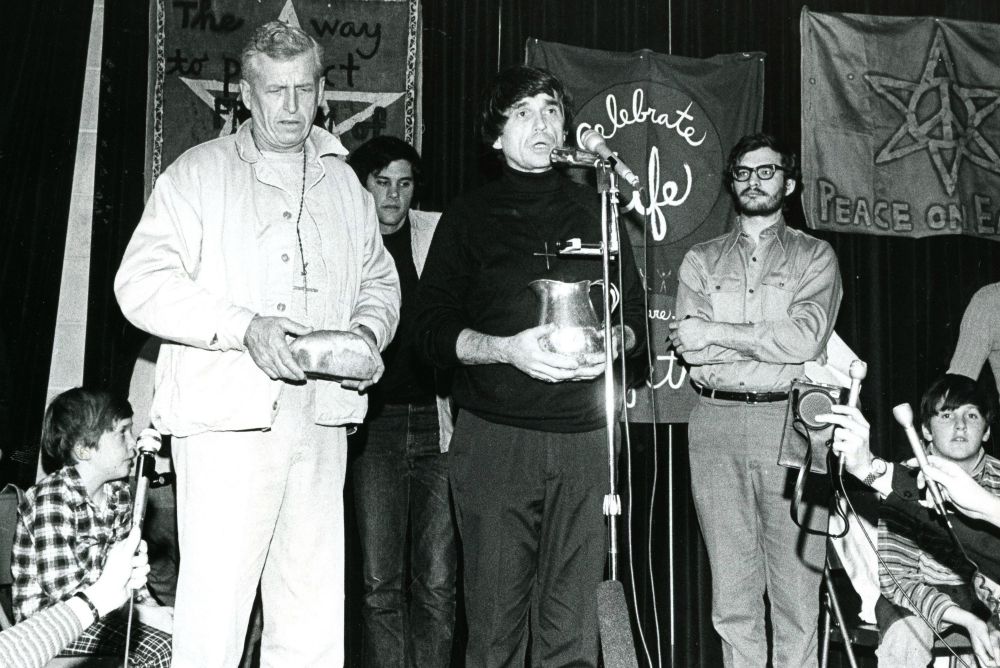

Then-Josephite Fr. Phil Berrigan, left, and his brother Jesuit Fr. Daniel Berrigan, center, participated in numerous anti-war activities beginning in the 1960s. They were part of the Catonsville 9, a group of Catholics who burned draft files outside of a draft board in Catonsville, Maryland on May 17, 1968. (CNS file photo)

Three years after his death, Daniel Berrigan, activist, priest and poet among many other things, still casts a long shadow, both on those who knew him personally and on those influenced by his steadfast opposition to military might, particularly nuclear weapons.

At a presentation that included remarks by biographer Jim Forest and author James Carroll, the late Jesuit was celebrated by a gathering that included former colleagues in the anti-war movement, friends, a few young admirers and those curious to learn more about his life and work.

Jointly sponsored by Orbis Books, publisher of Forest's Berrigan biography At Play in the Lion's Den and Villanova University's Office for Peace and Justice Education, the event, which also featured the unveiling of a new portrait of Berrigan by artist Ruane Manning, attracted more 50 participants June 9.

Berrigan was a gifted "patron saint of the nay-sayers," said Forest in a brief conversation before his talk. "Many people can say 'no.' But can you pick the right times and the right places to say no? And if there was a time when we needed to learn how to say no again, it's now."

At a certain point in the mid-1960s, Berrigan decided, said Forest, that his work as a priest and as a human being would be defined by the ways he found to oppose the Vietnam War and nuclear weapons.

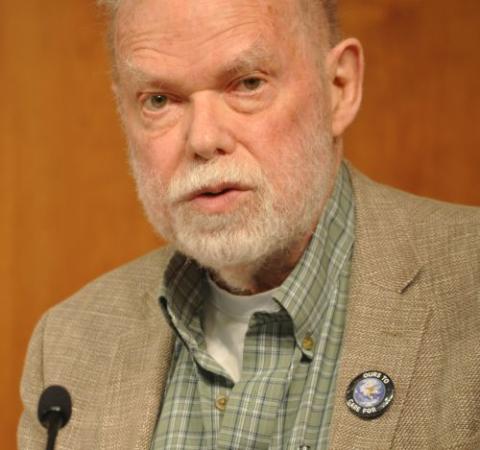

Jim Forest, Daniel Berrigan biographer, speaks at the celebration of Berrigan's life on June 9 at Driscoll Hall, Villanova University, in Pennsylvania. (Lance Woodruff)

Almost 45 years after the last troops left Vietnam, said Forest: "We still look back and see the consequences of that conflict reverberating. So many unnecessary wars, so much more militarization of society. Learning to say 'no' is real."

Now is the "time to learn to say not only 'no' to the government, but 'no' to those people around us who want to define, consciously or unconsciously, the direction we're going with our lives. That's the only thing we have to give," he added.

In a controversial article in the June edition of the Atlantic , bestselling writer James Carroll, himself a former priest, called for the church to do away with the priesthood. But it was Berrigan the priest who had had a profound effect on him as a young man. "No one had a more positive influence on my life than Daniel Berrigan. His witness on matters of war and peace and the Catholic faith was absolutely decisive."

In his speech at Villanova, Carroll traced a broad historical path, one that covered a thousand years of church history. Since the time of the Crusades, he said, Catholics had been identified as the just-war church. Then came the dawn of the nuclear age, the 1963 papal encyclical Pacem in Terris, and Pope Paul VI's heartfelt cry in a 1965 visit to the United Nations: "No more war, war never again."

Without the work and words of Daniel Berrigan (as well as that of Dorothy Day, Thomas Merton and people like Forest), said Carroll, "the change in Catholic attitudes wouldn't have taken hold the way it did on the public imagination. All of those people needed the elegance and clarity Daniel Berrigan brought to these new Catholic attitudes to war, and his personal witness." By the time of Berrigan's death, said Carroll, "the Catholic Church had become a full-fledged peace church, and Berrigan was crucial to that."

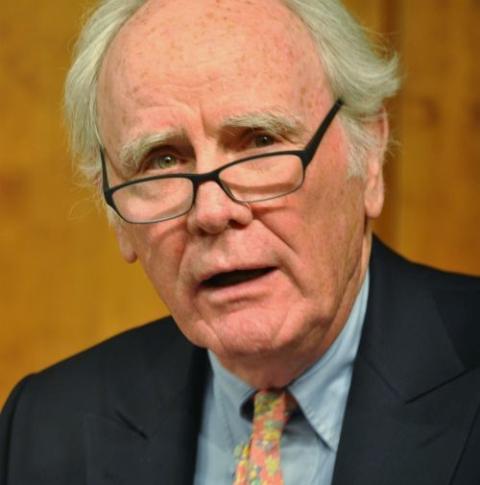

Author James Carroll June 9 at Driscoll Hall, Villanova University in Pennsylvania. (Lance Woodruff)

While Berrigan was a man of action and of words, said Carroll, "both his actions and his words were rooted in a deeply contemplative faith."

In his talk, Forest also underlined Berrigan's spiritual influence:

"I have known many people who lived what one might call Jesus-shaped lives, Dorothy Day and Thomas Merton among them. Dan was another," he said. "Such people remind those who encounter them of the Gospels. These are people who, in ways large and small, lay down their lives for their neighbor, including the hostile neighbor, the enemy. One can make no sense of the pivotal choices Dan made in his long life apart from the New Testament."

He continued, "His greatest gift may have been the path he opened (or in many cases re-opened) to eucharistic life and faith for people who had been estranged from almost everything."

Sitting in the audience was 25-year-old Nicholas Sooy, who works for the Orthodox Peace Fellowship in North America, and a friend of the Forests. As a peace studies major at Messiah College, Sooy had learned about Berrigan and his brother in a course on the history of peace, he said.

Advertisement

"I think the biggest takeaway for me is that you can't simply sit on the sidelines, stand and just pray for peace. But he [Berrigan] actually, whatever he had with his life — his life, his time, his freedom — he gave for the cause," said Sooy. "And unless people, especially young people like myself, really make it a priority that this is something we care about and we can't forget, then the threat's going to continue to grow and continue to be there."

Fellow poet and retired pastor of Philadelphia's St. Malachy Parish, Fr. John McNamee, who attended the Villanova gathering, hosted Berrigan when he was in the city and saw another side of the priest. While Berrigan would be remembered for his pacifism, he was also "extremely humorous," said his old friend. "Yeah, I guess his strategy would have been taken from the great Oscar Wilde." Then he shared the quip Wilde is attributed with: "Life is too important to be taken seriously."

Berrigan's legacy was deeply rooted in his devotion to Jesus Christ, said Carroll. "His spirituality defined his politics. There was a still center in Dan Berrigan that everyone who met him experienced. … He left a mark that can't be erased."

[Elizabeth Eisenstadt Evans is a freelance writer on the religion beat in the Philadelphia area.]