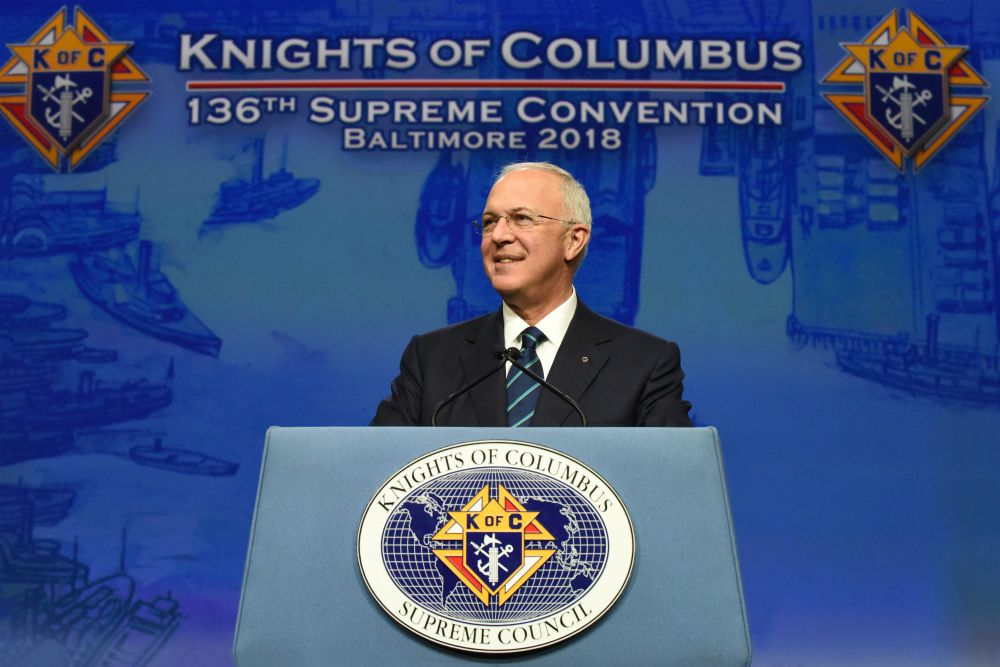

Carl Anderson, CEO of the Knights of Columbus, addresses attendees Aug. 7 at the 136th annual Knights convention in Baltimore. (CNS/Courtesy Knights of Columbus)

A small Colorado web design company that has filed a $100 million suit against the Knights of Columbus, alleging that the organization breached a verbal agreement and that it engages in fraudulent practices in its insurance business, will get its day in federal court.

UKnight, the design firm managed by plaintiff Leonard Labriola, claims that the Knights broke a verbal contract when the organization failed to honor a promise to make the firm the sole vendor for its life insurance business. Labriola also argues that the Knights systematically overstate the number of members in the organization, affecting the rating of its business by the insurance industry.

The Knights, in response, dismissed Labriola's claim as "a garden-variety business dispute brought by a website vendor that failed to close a business deal."

In their separate filings, both sides demanded a jury trial, and U.S. District Judge R. Brooke Jackson, in a July 25 order, scheduled an eight- to nine-day jury trial to begin Aug. 26, 2019, in Denver.

A core issue in the case is Labriola's claim that the Knights inflate the potential of the pool for their insurance business by failing to remove the names of individuals who no longer are dues-paying members of the Knights' local councils or who have died. On that issue, the court, in an order filed in March, ordered Knights of Columbus officials to turn over to Labriola a limited amount of data that would demonstrate whether, in a given month, the actual number of paid members matches the numbers claimed by the organization.

Several people familiar with the process of tracking membership rolls told NCR that inconsistencies in the numbers of members kept on the rolls at the national level and the number actually paying dues at the local level were common, but the reasons they gave for the discrepancies varied, from failure of local councils to cull the rolls to deliberate tactics at the national level making it difficult, if not impossible, to remove members from the rolls.

Advertisement

Jackson has already ruled on a variety of claims and counterclaims filed by the litigants, denying UKnights' motion that the court sanction the Knights for witness tampering during the discovery process and granting the Knights' motions to dismiss UKnights' claims that the organization violated the RICO (Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organization) Act. It also rejected UKnights' motion that the court order the IRS to revoke the Knights' tax-exempt status.

The Knights argued that the plaintiff had no right to the membership information because the material was irrelevant; that the plaintiff had "no standing to complain about" the organization's membership practices; and that "the First Amendment protects" the Knights from such an inquiry on religious freedom grounds.

Jackson wrote that the information is relevant because the plaintiff "theorizes that the Knights of Columbus was eager to contract with UKnight until the Knights of Columbus realized that the UKnight web platform would expose its fraudulent scheme." [italics in original]

Further, he wrote in his March order, "I am persuaded by UKnight's argument that at least a narrow subset … of membership information is relevant to UKnight's breach of contract and business tort claims."

Members of the Knights of Columbus pray during Mass Oct. 22, 2017, at St. Rafael the Archangel Church in Quebradillas, Puerto Rico. (CNS/Bob Roller)

Consequently, he ordered that UKnight "is entitled to the July 1, 2017 'Council Statement – Summary and Payment Coupon' " that was issued to each council. Currently, according to the Knights, more than 15,000 local councils, with a membership of 1.9 million, exist in the United States, Canada, the Philippines, Mexico, Poland, Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Panama, Bahamas, Virgin Islands, Cuba, Guatemala, Guam, Saipan, Lithuania, Ukraine and South Korea. Insurance is sold in the United States, Canada, Puerto Rico and Guam.

The coupon would show the number of members that the Knights of Columbus claims for each council "and thus the number of members for which each council is charged," according to the court document.

"UKnight is also entitled to obtain from each local membership secretary the number of membership cards that the membership secretary has issued," Jackson wrote. The cards provided by the secretaries will establish "how many members are indeed active in each council because the cards are only issued if a member pays his dues."

"In sum," Jackson wrote toward the conclusion of his order, "I find no merit in the hodge-podge of arguments the Knights of Columbus have put forth in what appears to be an almost desperate attempt to preclude any discovery concerning membership information." While he sees the relevance of the information to UKnight's claims of contract breach and misappropriation of trade secrets, Jackson wrote, "I disagree with plaintiffs' effort to turn alleged membership shenanigans into a RICO case."

In complying with the order, the Knights have produced more than 10,000 payment coupons that were sent to local councils on July 6, according to Kathleen Blomquist, senior director of corporate communications for the organization. "Knights of Columbus counsel and plaintiff's counsel worked together so that plaintiff's counsel could acquire the second portion of membership information requested by the plaintiff," she said in an email response to a question. "As a result, the plaintiff currently is in the process of collecting the information it is authorized to seek."

Business deal gone bad

In court documents, the small Boulder, Colorado, firm said it "designed a complex interactive system underlying easy-to-use website templates that link together and serve the specific needs" of the Knights of Columbus. The system, it said, enhanced the organization's "ability to attract new members, to keep members connected "and increase sales of KC's financial products."

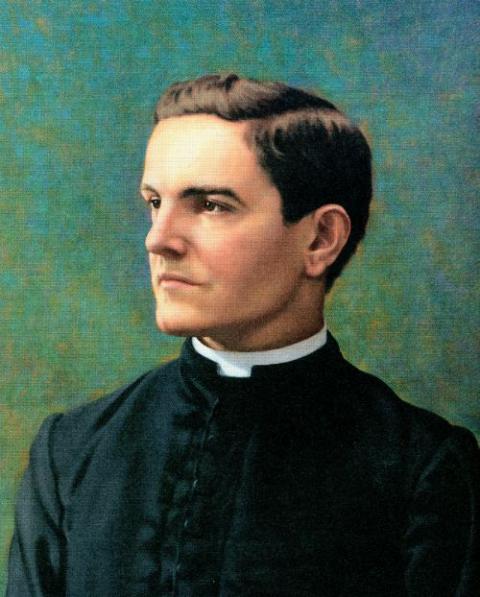

The Knights, based in New Haven, Connecticut, was founded in 1882 to provide benefits for newly arrived Irish immigrants, especially widows and children. It is a non-profit organization providing millions in charitable donations and donated volunteer hours, but it also funds conservative news outlets and conservative political organizations. As an insurance company licensed to sell to Knights of Columbus members only, it boasted more than $8 billion in insurance policy sales in 2016 with more than $105 billion in life insurance policies in force.

In its suit, UKnight claims that it began creating websites for Knights of Columbus councils, the local form of the organization, in 2009 and that the firm, on the basis of that success, was encouraged to propose a system designed for use by the entire Knights of Columbus organization. Beyond the council level in the United States are districts, comprising a number of councils, and state level organizations. The "supreme" level, headquartered in Hartford, Connecticut, and in charge of the Knights worldwide, is overseen by Supreme Knight Carl Anderson.

Labriola said he sent a proposal to the Knights in August 2011 and was invited to New Haven for three days of high-level meetings the following month. Those meetings went so well, said Labriola, that officials said his firm was "their choice as designated vendor for the entire Knights of Columbus fraternity." He said his firm agreed to several requests and modifications suggested by the Knights of Columbus legal department, and he was told that the order wished to see his program operating by February 2012.

Fr. Michael McGivney, founder of the Knights of Columbus and a native of Waterbury, Connecticut, is pictured in an undated photo. (CNS)

According to the suit, all the modifications and a new graphic design "and rollout plan" were finally approved by the Knights in August 2012. However, because of "internal issues" and the resignation in February 2013 of Pope Benedict XVI, the rollout was delayed and a formal contract was never executed.

Labriola, in a court filing, contends that the Knights provided his firm "with their standard vendor contract template to structure plans" for the website it would produce. By mid-August 2013, claims UKnight, the document had been approved by the legal department. It was sent for signature to Anderson, who "then promised that he would make the much-anticipated designated vendor announcement personally, and that he wanted to make sure his announcement made a 'big splash.' "

In response, the Knights, referring to the organization as "the Order," described UKnight in a court document as "a disappointed prospective vendor that offered the Order inferior and outdated website services that the Order refused to endorse. UKnight is now trying to accomplish through this lawsuit what it could not get through product development and sales negotiations."

According to the Knights' attorneys, Labriola "raised preposterous legal claims in an attempt to force the other side to pay money that is neither owed nor deserved." Among such claims, say the Knights, "is that the order supposedly gave UKnight an oral contract in which it would, on a single day, endorse UKnight's service and thereby confer on UKnight a $100 million value."

Another issue, which Jackson has permitted to go to litigation, is the Knights' claim that six years prior to filing suit, UKnight "began secretly and illegally recording phone calls" with Knights of Columbus employees and that those calls consequently "reveal that UKnight knew it never had a contract with the Order." The Knights further allege that UKnight has "relied on litigation funding from anonymous sources … in its attempt to shake down a windfall."

Keeping or dropping members is not simplified process

How relevant the membership question is to the rest of the suit remains to be seen, but if accounts of Knights at the local level are any indication, no simple formula exists — given the rules governing membership retention — for determining just how many legitimate members are on the rolls at a given moment.

Gregory A. Schuring, past district deputy of the Rockport Region in Illinois from 2015 to 2017, explained that the Knights of Columbus constitution "covers what you can do to get rid of a member, but it's a very complicated process." Dropping someone from the rolls, according to Schuring and others, can only be done after a series of steps have been taken to contact members and to see them personally.

Other incentives also may make district deputies and state leaders reluctant to drop members. First, councils and their corresponding districts aim for "star" status by keeping a certain membership level. Maintaining such a status is financially beneficial to the local council. Each council must pay a fee to the state and supreme levels for each member on the rolls.

Labriola contends that the supreme level is making significant revenue from councils that pay for members who shouldn't be counted because they don't pay dues, and he and others contend that councils must use funds from their own treasuries and from fund raisers that might go toward charitable work in order to pay for the non-existent members.

Blomquist, however, provided a table showing that during the past five years, membership dues constituted an average of only .16 percent of the supreme level's total revenue. In 2017, for example, membership dues totaling $3.2 million amounted to .14 percent of more than $2.2 billion in total revenue.

As a member of his council's retention committee in 2012, Jim Goode of Plano, Texas, said members of the committee were required to "physically or verbally make contact with every member who was in arrears and try to explain to them the benefits of the council and why it was important for them to be an active member, why it was important for them to pay their dues." He said he agrees with the requirement and that committee members "did what we could to have them become active in the council and also catch up on their dues because we had to pay both state and supreme per capita, which is like a head tax, for every member on our rolls."

Goode, who was grand knight of the St. Elizabeth Anne Seton Council last year and deputy grand knight for the previous two years, said the council's members pay a share of local dues to the state and the supreme levels, the latter receiving both a per capita amount for supreme's pro-life activity as well as Catholic advertising.

He said if the per capita charge is not paid to the state level, officials there have ways of shunning the offending council members at state conventions.

He and Schuring both said that non-paying members could range from 10 percent to 30 percent of a council.

"Now when you have 400 members and you have somewhere near 100 members, and sometimes over, who aren't paying their dues, then that means that you have to take the per capita money out of what other people are paying as dues or from some of your fund raisers," Goode said.

That level of discrepancy is not unusual, said Jerry Mishork, a member of a local council in Allen, Texas, and an IT professional who has volunteered his expertise in working with his council and others throughout the country.

Mishork has worked with UKnight, and has "come up with some ideas on improving their site — their features — make it more accessible with website responsive design, kind of push it to the limit and add more features." He and others interviewed by NCR vouch for the effectiveness of the UKnight system in connecting members and deciphering paying member from those who are inactive. The firm reports that more than 1,042 councils use the system.

Screenshot of UKnight website showing features that Knights of Columbus councils who are clients can use to manage membership.

As part of the legal process, Mishork has handed over email correspondence and has also been scheduled for deposition.

In a June phone interview, he said he works with councils around the country that use the UKnight system. "Pretty near everyone I've dealt with from other councils says when it comes time to do the UKnight membership thing and you look at the numbers — it comes down to what comes down from supreme is not reality."

According to Mishork and others, the UKnight system, which is accessed by active members using a password, shows the discrepancy between paid up membership at the council level and the rolls kept in New Haven.

There is a significant discrepancy between what several of those interviewed claim was the amount — around $12 — paid in total to supreme in per capita dues and fees and what the national office lists in its publications says is the actual amount charged. Blomquist produced a 2015 newsletter showing that the per capita charge for dues is $3.50 per year. She said the Knights also assess a $2 per person "culture of life" payment and "Catholic advertising fee" of $1 per member, bringing the total annual per capita cost to $6.50.

Annual dues at the council and state levels vary. Councils and districts can also earn discounts on member dues by achieving "star" status through a variety of membership and other incentives.

Ray Gentilini said he's held just about every position there is to hold at the local Knights level, including financial secretary — "the main guy involved in the retention program" — and his current position of retention chairman.

"I know that people think it is really a cumbersome process, and I thought that too when I was financial secretary and trying to do everything by myself," said Gentilini, a member of St. Paul's Council in Colorado Springs. "The secret to this is you have to do this on a collective, fraternal basis." If someone has been on the books for years without paying dues "that's the fault of the council."

The process is set up, he said, for tracking the occasional member who drops out or joins another church or decides that the Knights of Columbus is just not for him.

If there are huge numbers unaccounted for, that is a situation, he said, that takes a long time to develop and it will take a long time to correct.

In his circumstance at the moment, there were 15 members out of 142 who were not paying dues. Four of them showed up at a recent breakfast and decided on the spot to pay up. The other 11, he said, owe only one year in back dues, and members of the retention committee will contact each of them to see if they want to remain active members.

As he described the approach outlined in the organization's by-laws, the financial secretary sends out a bill each year no earlier than Dec. 15 and before Jan. 1. If there is no response, a second bill goes out about Feb. 1. If there is no response to that, two more letters described as "Knight alerts" go out, and if they are unanswered, then a notice is sent to supreme to drop the member.

At that point, other Knight officials at higher levels — district and state — may try to be in touch with the individual and members of the retention committee will try to make personal contact.

What about the claim that members are kept on the rolls even if they don't pay to increase the number of possible insurance prospects?

"Well I don't know anything about that. I never knew that there was a membership base important to the insurance business," said Gentilini.

[Tom Roberts retired in 2018 as NCR editor-at-large. He is the author of The Emerging Catholic Church: A Community's Search for Itself (2011) and Joan Chittister: Her Journey from Certainty to Faith (2015), both published by Orbis Books.]