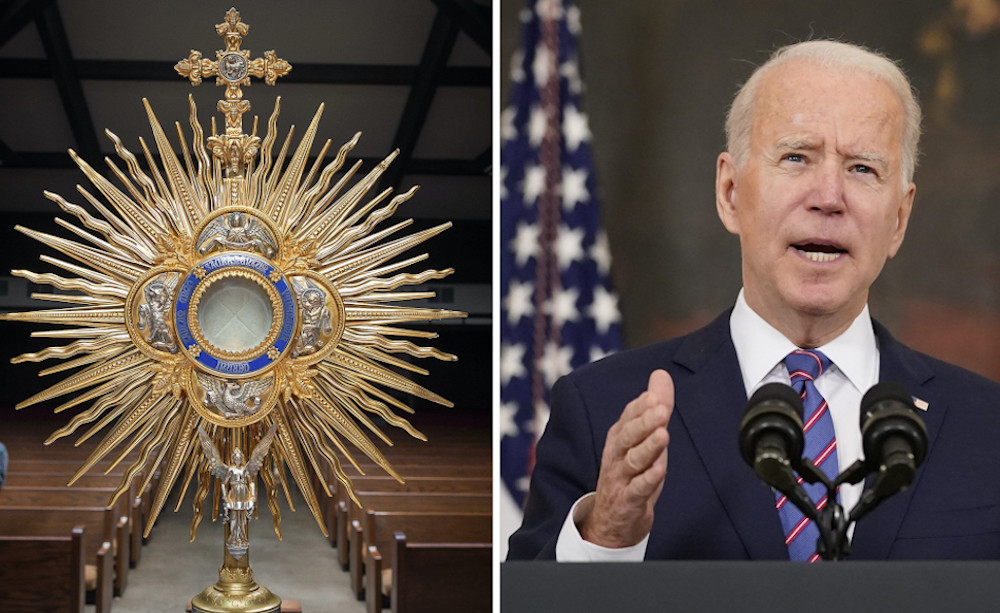

Holy Communion, left, and President Joe Biden have been a regular issue during Biden’s presidency. (Unsplash/Creative Commons; AP/Andrew Harnik)

When U.S. Catholic bishops huddle for their (virtual) annual spring meeting June 16-18, the prelates will debate a thorny theological issue: Should the sacrament of Communion be denied to Catholic politicians who back the right to an abortion, a practice the church condemns?

The bishops' debate won't decide that question directly — technically they'll discuss whether to draft a document related to the issue. Even then, a statement would not be binding: Each individual bishop retains the right to make decisions for their own diocese regarding the distribution of Communion.

And of the bishops who responded to a recent Religion News Service survey asking more than 180 members of the U.S. Catholic bishops' conference their position on such a Communion ban, few offered a firm yes-or-no answer.

Advertisement

"I think the Catholic faithful in general are in need of instruction as to what the meaning of the Eucharist is," said Colorado Springs Bishop Michael Sheridan, who has argued since at least 2012 that Joe Biden should not receive the Eucharist. He was also one of a small number of bishops who called for denying Communion to John Kerry during the then-senator's 2004 presidential campaign.

Nor do all the bishops see the politics of life issues in the same light. Many have mimicked the posture of Pope Francis and greeted Biden's presidential election as a welcome shift in immigration and environmental policy and other concerns. Some bishops have invoked Francis' inclusive description of Communion in his Evangelii Gaudium exhortation, which states the Eucharist is "not a prize for the perfect but a powerful medicine and nourishment for the weak."

But while not new or a matter of consensus, the threat of denying Communion over abortion has gained currency among a cadre of clerics since the November election, which put a Catholic in the White House for the second time — and the first since the landmark Roe v. Wade Supreme Court ruling on abortion — while chasing from office the most committed anti-abortion administration in recent memory.

Seemingly wishing to keep abortion at the center of the American Catholic conversation, a group of conservative bishops has driven the debate with uncharacteristically public pronouncements. Chief among them is San Francisco Archbishop Salvatore Cordileone, who released a letter in early May in which he told Catholic politicians to "please stop pretending that advocating for or practicing a grave moral evil ... is somehow compatible with the Catholic faith."

Cardinal Daniel DiNardo, left, of the Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston, and Archbishop José Gomez, of Los Angeles, speak during a news conference at the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops spring meetings on June 11, 2019, in Baltimore. (AP/Jose Luis Magana)

Many of the conservative bishops who replied to RNS' questions echoed Cordileone's implication that Biden and other Democratic Party Catholics led Catholics astray by example. In Sheridan's words, they "can lead others of the faithful to thinking, well, this must be all right."

This situation has a formal name in Catholicism: "scandal" — when "people who are representatives of the church engage in activities that mislead other people ... as to what the church believes," explained William Mattison, who teaches theology at the University of Notre Dame.

Several prominent Catholic politicians, including Biden and former New York Gov. Mario Cuomo, have largely avoided the charge of scandal by seeking to separate their personal opposition to abortion from public policy, arguing they have no right to impose their beliefs on all Americans.

"I really wish Mr. Biden and others were trying to find some restrictions on abortion policy," said Fr. John Beal, a canon law professor at Catholic University of America. "But they have, most of them, said very clearly they agree with the church's teaching but that they take a different tack on the public policy."

There is a pragmatic side of the question as well: "Here in the United States we have to be conscious of what can be done," Beal said in a nod to continued support for abortion rights among American voters, a dynamic that often shows up in public polling.

But these distinctions leave Bishop Thomas John Paprocki of Springfield, Illinois, unmoved. In a statement, Paprocki argued that politicians who promote or vote for "permissive" abortion laws not only give scandal but "manifest grave sin."

"It communicates to others that they, too, can vote for pro-abortion laws with impunity and with no adverse consequences to their reception of Holy Communion," Paprocki said.

"I think the Catholic faithful in general are in need of instruction as to what the meaning of the Eucharist is."

— Colorado Springs Bishop Michael Sheridan

This was also the concern of Bishop Liam Cary of Baker, Oregon, who made clear his support for denying Communion to politicians who back abortion rights. "Is it a political leader who professes himself to be Catholic? Will he set the terms for Communion for himself and, by implication, for others who share his view?" Cary said. "Or will the bishops, who have been charged with that responsibility?"

Threats of Communion bans are not exclusively a conservative tool. In 2018, Bishop Edward Weisenburger of Tucson, Arizona, suggested "canonical penalties" — which can include denying Communion — for Catholics who participated in the Trump administration policy of separating immigrant families along the U.S.-Mexico border. However, that overture failed to gain traction with other bishops.

As for the fight over Communion, liberal bishops have been reticent even in their opposition to a ban. In a May 13 letter to U.S. bishops' conference president Los Angeles Archbishop José Gomez, 47 diocesan bishops requested that the conversation about the Eucharist be postponed "until the full body of bishops is able to meet in person," and noted the Vatican's recent caution to the bishops to move slowly on the issue. Most of the signers have been reluctant to discuss the issue with the press: One of the bishops who signed the letter — Bishop Richard Pates, apostolic administrator for the Diocese of Crookston — responded to RNS, but only to say he is "working with my fellow bishops in the USCCB to arrive at a serene outcome to this question as (Vatican officials) so graciously advised us."

Alberto Rojas of the Diocese of San Bernardino, California, was the only cleric to respond to RNS with a definitive no, saying through a representative that he believes Catholic leaders should instead make an effort to speak privately with politicians who are in this category about the gravity of their support for abortion rights and how it conflicts with the values of their Catholic faith.

Rojas joins liberal-leaning clerics who have signaled willingness to allow politicians such as Biden to receive Communion — namely, Cardinal Wilton Gregory in Washington, D.C., who was part of the president's inaugural festivities, and San Diego Bishop Robert McElroy, who recently argued bishops shouldn't "weaponize" the Eucharist.

Members of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops gather for the annual fall meeting, on Nov. 12, 2018, in Baltimore. (AP/Patrick Semansky)

Conservative or liberal, however, there was a sense of general ambivalence regarding the issue.

New York Cardinal Timothy Dolan told RNS in May that he "probably" still supports a 2019 statement in which he suggested he would not deny Communion to Biden. After signing the bishops' letter of protest to Gomez last month, Dolan reportedly asked that his name be removed.

A representative for Bishop Michael Burbidge of Arlington, Virginia, pointed to recent comments in which he called the dialogue important but acknowledged concerns about the timing and virtual discussion format.

Bishop Felipe Estévez of St. Augustine, Florida, did not close the door on denying Communion to politicians who back abortion rights but framed the approach as a "pastoral process."

"I need to be in the process with the lawmakers, because the Holy Spirit is in the process — bringing light, wisdom, knowledge," Estévez said.

But a pastoral approach does not take a Communion ban off the table. Denver Bishop Samuel Aquila specified that clerics should have a private conversation with a lawmaker, followed by a separate dialogue with other witnesses present.

If the lawmaker still supports abortion rights, he said, then bishops should "ask the person to refrain from Communion."