A half-barefooted homeless man walks up the steps April 14, 2022, in Los Angeles. (AP photo/Jae C. Hong)

I was drawn to Tracy Kidder's latest book, an investigation of homelessness, with three questions in mind:

- What's it like to be homeless?

- What can those of us with homes do to help?

- What can we learn from Dr. Jim O'Connell, the Boston physician who has devoted his life to caring for people on the streets? (The book held particular interest since O'Connell and I went to college together and we've remained friends since.)

Kidder has found a technique that works: Explore a complex topic that's baffling to most readers through the eyes of a main character the audience can relate to. Among his most notable works in this genre is Mountains Beyond Mountains, his 2003 book about the late Dr. Paul Farmer and his work in global public health.

In Rough Sleepers: Dr. Jim O'Connell's Urgent Mission to Bring Healing to Homeless People, Kidder wastes no time addressing my first two concerns (the title is derived from the British term for people living without a roof over their heads). On the page following the book's dedication, he shares a poem written by U.S. Army veteran Michael Frada, who for many years was homeless and a patient of O'Connell. It is titled, "I Am," and concludes:

So if we should meet for a moment on my life's journey

Smile at me, talk to me, or simply be still

And know that I am.

Cover art for the book Rough Sleepers (Courtesy of the publisher)

Frada underlines an approach that O'Connell learned the hard way. Kidder recounts O'Connell's first day on the job in 1985, a transition from a prestigious role as senior medical resident in the intensive care unit of Massachusetts General Hospital to showing up for work at a homeless shelter.

Learning to listen

After three years of residency and four years at Harvard Medical School, O'Connell was taken aback when a nurse informed him: "You've been trained all wrong."

The nurse was Barbara McInnis, who was also a lay Franciscan.

"You have to let us retrain you," she told O'Connell. "If you come in with your doctor questions, you won't learn anything. You have to learn to listen to these patients."

And the best way for O'Connell to learn that, she insisted, was soaking the feet of the clinic's homeless patients. For more than a month.

Kidder reports:

Foot soaking in a homeless shelter — the biblical connotations were obvious. But for Jim, what counted most were the practical lessons, the way this simple therapy reversed the usual order — placing the doctor at the feet of the people he was trying to serve.

Nearly 40 years later, O'Connell and his colleagues have built an innovative model for homeless medicine. Among the services they provide is a 24/7 respite center for patients "too sick to return to the streets or a shelter but not sick enough for an acute hospital stay." The center is called the Barbara McInnis House.

Among the cities O'Connell has worked with on the problem is Los Angeles, where an estimated 50,000 people are homeless; the number is about 6,000 on any given night in Boston. Another difference: Only about 5% of Boston's homeless population stays on the streets and the rest are in shelters. He says the opposite is true in L.A., with 80-90% living on the streets and the remainder in shelters. Nationwide, the federal government put the homeless population at 582,462 in 2022, a slight increase over 2020.

Dr. Jim O'Connell (Courtesy of Jim O'Connell)

In L.A., O'Connell has become friends with Jesuit Fr. Greg Boyle, founder of Homeboy Industries and pastor to L.A. gang members past and present. The two share a commitment to listening as Job One of their respective ministries.

Kidder first encountered O'Connell in 2014 when he tagged along on a van ride with the Street Team of the Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program, or BHCHP, the organization O'Connell co-founded in 1985 and has worked for ever since.

Kidder and O'Connell make clear that the book is not a collaboration — it's Kidder's book — but they've appeared together in a number of settings to discuss it.

The story of 'Tony'

Kidder didn't spend all of his time following around O'Connell. A strength of the book is the time the author invested in getting to know people whose daily lives on the streets are almost unimaginable to the rest of us.

He focuses on someone he assigns the pseudonym "Tony," and traces his story from a troubled childhood to his later life as a rough sleeper with a range of medical issues addressed by O'Connell and colleagues. In between was an 18-year prison term for "assault with intent to commit rape."

At 6'4" and nearly 300 pounds, Tony was known in prison as "Big Man." After his release, he served as a protector of more vulnerable men and women with whom he shared doorways and heating grates. Among the book's poignant moments is Kidder's account of Tony encountering O'Connell and his wife, Jill, and daughter, Gabriella, at Boston's main train station. From his coat, Kidder reports, Tony "produced a gift-wrapped package, a brand new Cabbage Patch doll for Gabriella."

Kidder adds:

Later, Tony told Jim, "A lot of people steal for their kids. I'm like, Come on, stop smoking your crack for a day and buy the kid something legit, don't give the kid stolen stuff." This by way of assuring Jim that the doll wasn't stolen.

In describing a brutally abusive childhood, Tony initially disputed claims by his friends that the priest in their parish in Boston's north end had abused them — and he said the priest never abused him. But he later told Kidder that he had been abused by the priest and provided his name, Alan E. Caparella. That prompted Kidder to do more research. BishopAccountability.org reports that a settlement (not brought by Tony) was reached against Caparella in 2013, after his death.

"I never told on him," Tony told Kidder. "He raped me with candles and stuff."

Tony also told him: "So between my family and everything else, OK, I knew back then when I was a little kid, there's no such thing as God."

O'Connell said he'd encountered some but not many cases of homeless people abused by priests, noting:

The number of homeless people who have suffered abuse — either sexual, physical or emotional — as children is truly extraordinary. It's way over 70 or 80 percent. I almost didn't believe it at first. I wouldn't say many [homeless people allege clergy sexual abuse], but one man in particular has a history of being arrested for destroying the doors of churches — his way of acting out what was pretty horrible abuse.

A winding path to med school

A 1970 graduate of the University of Notre Dame, O'Connell moved in several directions before deciding on medicine. After college, he earned a master's degree in divinity from Cambridge University in the U.K., taught and coached at St. Louis School in Hawaii, briefly served as a teaching assistant to philosopher Hannah Arendt in Manhattan, managed a restaurant in Rhode Island and pooled resources with a friend to buy an old dairy barn in Vermont.

Cover art for Jim O'Connell's book Stories from the Shadows: Reflections of a Street Doctor (Courtesy of the publisher)

He said his decision to enter medical school at age 30 was prompted by the experience of sitting, helplessly, with the victim of a motorcycle accident until help arrived, not all that quickly.

"He was this tough, tough guy with a leg broken in half, which I couldn't even look at," O'Connell recalled.

Perhaps uncertain whether he would survive, the man shared with O'Connell intimate details of his life like his recent divorce and the sexual abuse he suffered as a child.

The encounter left O'Connell realizing how much he valued such conversations — but also how determined he was "to learn how to fix that leg."

He also credits his upbringing: "I realized I was in search of something that I think probably comes from Notre Dame. It certainly comes from growing up in a parish in an Irish Catholic part of town where you wanted to do something that would make your life meaningful and be sure you're giving back. I was really looking to be able to have some skill where I could give back."

What people of faith can do

Given Catholic social teaching, statements by the U.S. bishops' conference and what Pope Francis has said and done about homelessness, there's good reason for Catholics to want to do something about it. In a recent interview, I asked O'Connell for examples of Catholic organizations that have been especially helpful — and what more they might do.

"It's been remarkable, at least in Boston, how much Catholic and other religious organizations have done for the homeless problem," he responded. He listed some local examples:

The Franciscans at St. Anthony Shrine have basically opened their building to whatever might be needed. We cherish them. Their Lazarus program for people who die with no family and no friends provides a dignified service [and burial] for people who otherwise would have been left in a morgue or buried in a pauper's field. They also have a clinic at the shrine dedicated solely to homeless women.

St. Francis House, started by the late Fr. Louis Canino, has evolved from a bread line and a soup kitchen into Boston's largest day shelter. They have showers, they have meals and BHCHP has a clinic there that is as busy as you can imagine. Even though their funding has become quite secular, their spirit is still very much a social justice one.

O'Connell said a group of downtown churches had gotten together years ago and decided to provide meals on various nights "so homeless people had a safe place to go every night for a meal and a lot of accompaniment."

Advertisement

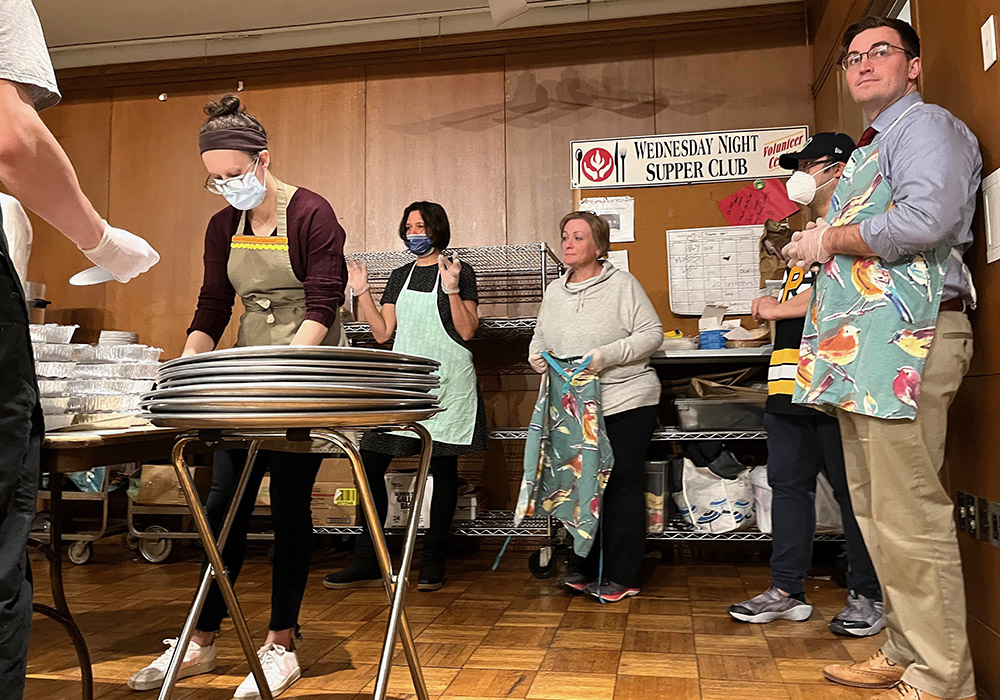

Among those dinners is the Wednesday Night Supper Club that the Paulist Center started more than 50 years ago. My wife and I are center members and before the pandemic were occasional Wednesday night volunteers. I returned a couple of weeks after reading Rough Sleepers, in part to get a more personal feel for the issues discussed in the book.

By 6 p.m., several dozen men and one woman had arrived at the center, which borders the 50 acres some of them call home — the oldest public park in the United States, the Boston Common, established in 1634.

After a dinner of chicken nuggets, beans and cornbread, several of the guests lingered to talk with the volunteers. One of the guests stroked his long white beard as he spoke with Anna Costello Duran, the center's young adult minister and someone he'd spoken with during a previous dinner at the center.

His eyes lit up when Costello Duran reminded him of their earlier conversation about the Muir Woods, the Bay Area park they had visited — decades apart — when each lived in California.

Another guest approached volunteer Margaret MacNeil as she was heading out the door, asking if he could have another cup of tea. MacNeil gladly obliged, telling me later: "We might have been the only person they've spoken with all day, at least the only person who spoke to them without a grimace or a scowl."

Volunteers at the Paulist Center's Wednesday Night Supper Club on March 1 in Boston (NCR photo/Bill Mitchell)

Systemic causes and solutions

Addressing the root causes of homelessness is more challenging than providing a decent meal at the end of the day, a blanket in the park or even a shelter bed for the night.

Kidder points out:

It was obvious that [O'Connell] and his colleagues weren't addressing the many root causes of their patients' misery. … How do you treat physical illnesses in mentally ill patients and patients whose days and nights are ruled by the consumption of alcohol, the search for narcotics?

Asked what can be done, O'Connell told me:

I have struggled a lot with this. [As much as] we try to ease whatever suffering we can, to make their lives less onerous, to minimize suffering, the problem has become more complicated than any of us tend to realize. I look at homelessness as a prism you can hold up to society and what you see refracted are the weaknesses in our educational system, our welfare system, our foster care system, God knows our corrections system, all the poverty and racial issues that need to be addressed.

O'Connell credits Boston Cardinal Sean O'Malley with doing his best to be helpful on the homeless issue.

"Public opinion is very influenced by what the cardinal says," O'Connell said. "He has expressed interest in homelessness and has got some pretty amazing people together to see what can be done. The archdiocese has land and rectories that could be converted into housing but that's tricky because so many dioceses are under financial stress. So selling property becomes very important."

The church in Boston has considerable property that could be rehabbed for homeless people, but the archdiocese has relied on property sales to help cover the tens of millions of dollars it has paid out in settlements to victims of clergy sexual abuse.

While affordable and subsidized housing has been considered an obvious solution to homelessness, O'Connell says experience shows it to be a necessary but insufficient step.

Fifty years ago, court rulings resulted in the release of tens of thousands of mental patients from institutions around the country. Without supportive services to help them adjust, many of them floundered and ended up on the streets. More recently, homeless people provided with housing are discovering the pitfalls of a similar lack of services as they struggle to manage their newly sheltered lives.

O'Connell's team worked with homeless people who have experienced the phenomenon in creating a video aimed at addressing it: "New Place, New Problems: Unanticipated Struggles with Being Newly Housed."

What can church groups and individuals do?

"Befriending people newly in housing, inviting them to dinner, making sure they know where your parish is and that they feel welcome — all those things would be absolutely fabulous and very doable."

What about panhandling — and extreme cold?

At one point, O'Connell got in trouble with the board of the organization he runs for occasionally handing out cash to rough sleepers — five or 10 or 20 dollar bills. When staff reported that patients insisted on seeing only him as a result, he agreed to stop the practice.

When I asked him for advice about how the rest of us might respond to panhandling, he recalled advice he got from the late Barbara McInnis, the nurse and lay Franciscan who introduced him to foot soaking:

I remember asking (her): "I come to the clinic and 45 people are asking me for money. What do I do?" Her take was: "You don't have to give them money. You can if you want. But please look them in the eye and say, 'No, I don't have any money today. But how are you?' Her point was that most people are just looking not to be invisible, which is how they feel most of the time."

What to do when you encounter a homeless person, sometimes asleep or otherwise unconscious, who is exposed to the kind of extreme cold some of the country has experienced this winter?

I did a Q&A with O'Connell on the question back in 2014, when Boston was hit with an especially brutal cold snap. He acknowledged how little he learned in medical school about frostbite, hypothermia and a dreadful phenomenon known as "autoamputation." He was clear about what to do: Don't hesitate. Call 911.

Author's note: In addition to Rough Sleepers, material for this article was drawn from a conversation with O'Connell last month and from his memoir, Stories from the Shadows: Reflections of a Street Doctor, published in 2015.

[This article was made possible by a grant from the Hilton Foundation.]