(Unsplash/neONBRAND)

University of Chicago Divinity School student Rebecca MacMaster entered seminary out of a desire to make the Catholic Church "the best it can be" and to answer a calling to teach and work in college or parish ministry.

"My Catholic identity is so important to me, and it informs so much of how I interact with the world," said MacMaster, who is a candidate for a master's in divinity. "I know the Church can be a force for good and instrumental change in the world, and it became very important to me to help affect that change."

MacMaster wouldn't pursue ordination if it were available to women and has not felt excluded from any forms of lay ministry by her gender, she said in an email interview. Even so, she has often felt that other Catholics expect her to pursue children's ministry, or that her gender and age have caused her to be "talked over or pigeonholed into certain affinity ministries" in her work in the church.

In her multifaith seminary, she has experienced misogyny and anti-Catholic sentiment. Despite these experiences, MacMaster remains committed to her calling: "If I have to carve out a niche for myself, I will."

"Everything I've experienced has only made me stronger in my conviction to help all feel at home in their faith — to see themselves in this beautiful community," she wrote.

MacMaster's experiences and feelings about women's work in the church aren't uncommon, according to a recent survey conducted by the Women's Ordination Conference (WOC).

Titled "Mainstreaming Women's Ministries in the Roman Catholic Church," the survey found that 82% of those surveyed felt that women's ministries were not valued equally to men's. Of the 224 young Catholic women in formation and ministry in the U.S. who responded, 80% were dissatisfied with the ministry opportunities available to them in the global church, and 73% said the same about local opportunities.

Although the survey respondents overwhelmingly described their Catholic identity as "extremely important," they also described a lack of women's leadership opportunities, financial insecurity and clericalism as barriers to fulfillment of their ministerial paths.

"What this survey affirms is that women of the church are overwhelmingly educated and trained and thoughtful Catholic leaders, and they will persist," said Kate McElwee, executive director of the Women's Ordination Conference.

But they will "persist to a point," McElwee said, referring to young Catholics who choose to disaffiliate with the institutional church.

"It's a loss that's happened for many generations before this one, and our hope is that we can work to support these women to stall their exit," she said.

McElwee said the survey was a response to the resurgence of her organization's Young Feminist Network and Women's Ordination Conference members struggling with ministerial discernment after completing pastoral degrees.

Many respondents signaled that Catholic identity is "fundamental" to them, and 82% attend Mass at least once a week. The report cites women's inclusion and ordination as the most common changes respondents wished to see in the church, with 30% saying they would pursue ordination in the diaconate or priesthood if they could.

Although many respondents identified vocations that did not fit within the existing structure of the institutional church, 82% would not seek ordination through an independent Catholic movement, a statistic McElwee called "surprising."

"A lot of the members of the WOC really look to those movements as prophetic witnesses, living their vocation and modeling a new, renewed ministry," she said. "To see that that really didn't seem like an option to the survey respondents is interesting for our movement to consider."

For Madison Chastain, a recent graduate of the University of Chicago Divinity School, elements of the Women's Ordination Conference survey ring true. After a "transformative experience in Confirmation," Chastain pursued a variety of work in and around the church, including peer ministry at her Catholic college, volunteer teaching at a Catholic middle school, and youth ministry as a graduate student.

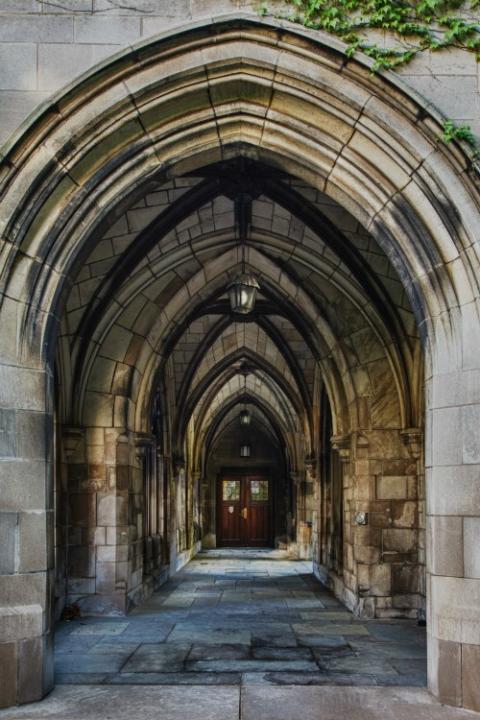

An archway that runs along Bond Chapel, adjacent to the University of Chicago Divinity School (Wikimedia Commons/Don Burkett)

She currently works with L'Arche, an organization that serves people with intellectual disabilities, and with another organization dedicated to helping students explore Catholic intellectual tradition.

"I know this is not a universal experience, but I firmly feel like I can sustainably do the work I want to do for the church within the church, and that work is not tangential to my primary vocational goals — it is my vocational goal," Chastain wrote in an email.

Chastain said although she doesn't want to give homilies, she does feel called to the diaconate and "would love to preside over baptisms, marriages, and funerals ... to proclaim the Gospel at Mass and assist with the consecration of the Eucharist."

But when she recently voiced this calling in a Facebook group for feminist Catholic women, Chastain got "dozens" of replies, some of which "implored [her] to reconsider the call" because she didn't want to preach.

"It was so discouraging," Chastain wrote. "This is where I really agree with the WOC study. It is clear that simply ordaining women is not the answer to the clericalism of the Church or the air of exclusion around the priesthood. Women participate in the assumption of the 'ideal type' of minister, priest, and deacon too."

Even so, Chastain said that while there are changes to the church's traditions and theology she would like to see, she remains committed to working within the church and its teachings. "I profess my loyalty to the Church's beliefs and tradition every Sunday at Mass, and as human and imperfect as the Church can be, I also firmly believe that I have a responsibility to abide it while I work towards change within it," Chastain wrote.

But an adviser to Catholic students at Harvard Divinity School said she has observed a "frustrated realism" about the career opportunities available to women in the church.

Catholic female Harvard Divinity graduates often pursue careers such as hospital chaplaincy or teaching "because there's only so much that they're allowed to choose from," said Patricia Simpson, an instructor in ministry studies, who distributed the Women's Ordination Conference survey to students.

Self-identified Catholics have been the largest denominational group at Harvard Divinity School for decades, and the majority of those Catholics have been women, Simpson said.

"The frustration is definitely palpable," Simpson said about women who see greater opportunities for male students, who can choose to be ordained.

The Master of Divinity degree is important to those female students, she said.

"I think it's because they want that professional degree, and they want the respect that should come with that," Simpson said. "I think they want to be able to state that they've prepared academically to the same level as ... the men being ordained."

Advertisement

While there is a certain optimism among younger students that women's opportunities will continue to expand, many older students who participate in Catholic student organizations have left the church to follow calls to ordained ministry in other denominations, she said.

At the Catholic University of America, where surveys were also distributed, younger undergraduate women generally accept and agree with church teachings on women's ordination and do not feel barred from the ministries they wish to pursue, such as teaching or faith-based social service, according to Susan Timoney, associate professor of practice pastoral studies.

However, the opinions of graduate students — who may come with work experience in ministry — and the broader population at Catholic University are more varied. "I think in some cases [graduate students] would hope to see themselves as being able to raise the profile of women and want to address some of the inequalities they see or that they themselves have experienced," Timoney said.

Yet the issue of women's roles in the church "isn't a defining issue," she said, especially for the younger students.

"Maybe it's because they are one of the first generations that have seen women in so many positions of leadership," Timoney said. "I also think that ... at the undergraduate level, they still feel like they see things opening up; they don't feel that there's more doors closed than might be open."

Ahead of National Vocations Awareness Week in early November, the Women's Ordination Conference will send its survey data and invitations to dialogue to various committees of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, including the Committee on Laity, Marriage, Family Life and Youth, and the Committee on Clergy, Consecrated Life and Vocations.

McElwee said the Women's Ordination Conference's primary goal beyond distribution is to "listen to the women who took the survey and to respond as a community" in the form of discussion groups and conversations among members of the Women's Ordination Conference and its Young Feminist Network.

The survey and the discussion it generates will show "women who are persisting in their faith and in their ministry and in their careers know that they're not alone," she said.

[Alexandra Greenwald is a freelance writer based in Chicago.]