A bomb sapper demonstrates how the team of specially trained demining experts does the initial search for antitank mines. If the metal detector identifies something, they mark it for hand excavation at a later time. (NCR photo/Melanie Lidman)

Fifty years after the monasteries around Jesus' baptism site on the Jordan River were an active war zone, bomb sappers from a British charity are making progress to remove 6,500 estimated landmines and booby traps lining the holy site. One of the first church buildings cleared of landmines belonged to the Catholic Church.

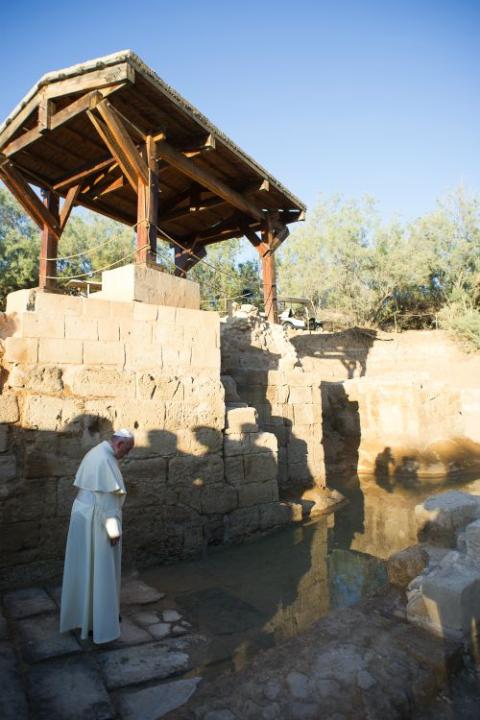

There are seven buildings in the "Land of the Monasteries," a cluster of churches, chapels, guesthouses, and monasteries nestled in the barren desert next to the Jordan River. Seven Christian denominations each maintained their own courtyard, serving the thousands of pilgrims who came to dip in "Bethany Beyond the Jordan," where John the Baptist is believed to have baptized Jesus. Both Jordan and Israel claim that Bethany Beyond the Jordan is on their side of the river, and religious buildings sprang up on both banks to serve the pilgrims. During his 2014 visit to the Holy Land, Pope Francis visited the Jordanian side.

Pope Francis visits Bethany Beyond the Jordan, the traditional site of Jesus' baptism, southwest of Amman, Jordan, May 24, 2014. (CNS/L'Osservatore Romano)

The Franciscan chapel, a squat, round building with curving staircases, was built in the 1920s during the British Mandate, on the Israeli side of the river. The white stones of the building melt into the reds and tans of the arid Jordan valley, just a few miles north of the Dead Sea. The chapel's monastery used to house about a dozen priests, who grew dates and grapevines in the courtyard's desert soil and made wine.

Today, the face of the chapel is pockmarked with bullet holes, a remnant of the fierce fighting between the Israeli army and Jordanian forces during and after the Six Day War in June 1967, when Israel expanded its territory. Here, the Jordan River is just a dozen feet wide and not very deep, making it a popular place to cross the border.

In 1968, the Israeli army declared the entire area a closed military zone. They seeded the land with thousands of antitank landmines, and booby-trapped the church buildings to make sure Jordanian militants weren't using the abandoned churches as staging grounds for attacks on Israeli settlements.

For 50 years, no one stepped foot in the church buildings. The monasteries were abandoned in the middle of daily life, with old winemaking equipment rusting in one corner and a shoe forgotten on a staircase in a hurry, now encrusted in half a century of dust. In the Ethiopian church, the bright yellow paint in the chapel is still visible beneath 50 years of bird droppings.

The Franciscan chapel was for a monastery that once housed about a dozen priests who grew grapes and dates in the courtyard. (NCR photo/Melanie Lidman)

Israel declared peace with Jordan in 1995, but the baptism site remained closed, strewn with landmines.

In 2000, Israeli authorities cleared the landmines along a narrow access road leading to the baptismal site for the visit of Pope John Paul II. In 2011, authorities opened the road to pilgrims for the first time, allowing access to the river but not to the monasteries.

About 800,000 people came to the site in 2018, especially around the feast of the Epiphany, celebrated by Orthodox Christians on Jan. 18 or 19 and marking Jesus' baptism. On their way, they passed the shuttered church buildings, yellow signs flapping in the wind bearing warnings about landmines.

Advertisement

Despite more than two decades of peace between Israel and Jordan, removing the landmines required negotiations between an ever-shifting body of stakeholders: the Israeli Defense Ministry, the Israeli army, the Israeli Civil Administration that oversees administrative issues in the Palestinian territories, the Nature and Parks Authority, the Tourism Ministry, the Palestinian Authority, and other Palestinian and Christian groups. But most importantly, anything done in the Land of the Monasteries required the cooperation of all seven denominations of Christianity present: Catholic and Syrian, Greek, Russian, Romanian, Coptic and Ethiopian Orthodox churches.

The region does not have a good record of cooperation between Christian sects. Fighting between Catholic and Orthodox groups over the keys to the main door of the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem was one of the main catalysts of the Crimean War in the 1850s, responsible for the deaths of three quarters of a million people.

Halo Trust, a U.K.-based de-mining group that operates in 27 countries and territories around the world, has led de-mining efforts in Israel and the Palestinian territories for the past eight years. According to the Wall Street Journal, there are approximately 35 square miles of land with mines in Israel and the West Bank, especially in the Golan Heights and along the borders. The Land of the Monasteries is about a third of a square mile.

Halo Trust spent years of negotiating with representatives from each Christian denomination, an effort that was also shared with Pope Francis. Although the landmines do not pose immediate risk to the public, like at other sites where Halo Trust is working, the organization believes the demining efforts send an important message of interfaith tolerance.

"The chance to clear this very historic place of the mines is going to have not only implications for the area because it will allow people of faith to return and worship in those churches," said James Cowan, the CEO of Halo Trust, when the project was first announced in 2016.

A sign warns of mines in the Land of the Monasteries. Bomb sappers still have about 5,000 booby traps and mines to remove from the area. (NCR photo/Melanie Lidman)

"But it will also have wider implications because it means that all three faiths are working together and all seven Christian denominations have been working together. And I think, in an age in which, elsewhere in the world, religious or historical sites are being damaged and pulled down, for humanity to be working together to restore something as huge as this has symbolic implications."

The project was initially slated to begin in 2016, but problems with funding from Israel's Defense Ministry delayed the start for two years. The demining efforts finally got underway this past spring. Halo Trust fundraised about $2.6 million, and the Defense Ministry is funding $2 million.

The prayer room in the Ethiopian Orthodox chapel has soaring ceilings and bright paint, but decades of bird droppings and dust. (NCR photo/Melanie Lidman)

A team of 22 specialized bomb sappers from the country of Georgia, along with dozens of Palestinian support staff have cleared 1,500 landmines from three of the seven church compounds, officials announced in mid-December 2018.

Marcel Aviv, the head of the Israel National Mine Action Authority, a branch of the Defense Ministry, said he hopes they will finish the work in December 2019. There are still about 5,000 landmines left to clear.

The Greek Orthodox monastery is one of the oldest buildings in the area, built around the fourth century. The Ethiopian monastery doubled as a guest house for pilgrims and is one of the largest.

"In 10 to 20 years, we will have all mines in Israel cleared, including Golan Heights and Syrian border," Aviv said. "It's our vision that there will be no land mines on the borders of Israel."

Clearing the mines requires bomb sappers to carefully scan the area with hand-held metal detectors, marking areas that require hand excavation of the old mines. The Israel army provided maps of some of the mined areas, but because the site is located on a flood plain that is inundated with water each winter, the mines have shifted over time. Additionally, the area is strewn with unexploded mortars and other detritus of years of fighting.

Bullet holes inside of the Ethiopian Orthodox church show the fierce fighting that took place in the area. (NCR photo/Melanie Lidman)

Excavated mines are brought to a safe area for a controlled explosion. Because of the historical buildings in the area, the sappers do not explode anything on the site.

This process can take weeks for each compound, as sappers go over every millimeter of the courtyard at least three times to make sure nothing has been left behind.

Many of the church courtyards had intricate agricultural irrigation systems that required dismantling.

After clearing the courtyards, the sappers move to the church buildings, which take a day or two to clear of booby traps.

"The booby traps are often near doors or windows, where they expected people to pass," explained Moshe Hilman, the National Mines Authority supervisor of the Qasr al-Yahud site. He said Halo Trust has exacting safety requirements, meaning workers plan ahead for how they will open every single door, window and drawer.

Dec. 9, 2018, view of Jordan River, showing site where Jesus is believed to have been baptized. The rope with the buoys marks the border between Jordan and Israel. (NCR photo/Melanie Lidman)

Christian pilgrims dip in the water April 10, 2018, at the baptismal site known as Qasr al-Yahud on the banks of the Jordan River near the West Bank city of Jericho. Israel is in control of the area and is working with Halo Trust to remove landmines in the area. (CNS/Debbie Hill)

After the site is deemed mine-free, each church community will be able to return to their sites. Aviv, head of the Mines Authority, believes the number of visitors will triple once the churches have unfettered access to their buildings.

The site also has economic importance for the region. Christian tourism is increasing at a steady rate, following general increases in tourism to Israel. Over 2 million Christian tourists came to Israel in 2017, accounting for 55 percent of all incoming tourists, according to the Israel Tourism Ministry.

The Qasr al-Yahud site is also holy to some Jews. Qasr al-Yahud is Arabic for "The Castle of the Jews," and some believe this was the spot where the Jewish people crossed into Israel for the first time after leaving Egypt. It is also believed to be the site of Elijah's ascent into heaven in a "chariot of fire" and the place where Elisha performed miracles.

"This is such a special place to be as a Christian," said Agneiszka Witek, a pilgrim from Warsaw, Poland, on her first trip to Israel, as she took in the baptismal site on the banks of the Jordan River in mid-December. Twenty feet away, a rope with plastic buoys marks the border with Jordan, and a Jordanian soldier waits, looking bored, on the Jordanian side, waving to tourists across the border.

"I'm happy for the peace between Israel and Jordan on this river," Witek added, when she heard about the mine clearing actions. "It's really important. I believe they can live together on the same river."

[Melanie Lidman is the Middle East and Africa correspondent for Global Sisters Report.]