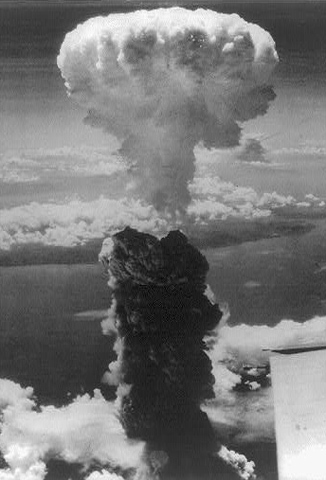

A column of smoke rises over Nagasaki, Japan, after an atomic bomb hit it Aug. 9, 1945. (Library of Congress)

After a typhoon chased us across the main island of Japan, my family and I found ourselves marching in the rain up a long hill in the middle of Nagasaki in search of the Urakami Cathedral. With the approaching 69th anniversary of the atomic bombing here in 1945, we felt a sense of awe and apprehension as we made our way with a stream of pilgrims and tourists through the grand Peace Park near the hypocenter. A sculpture trail, mostly donated by former Soviet-bloc countries, marks the path to a muscular 33-foot-tall peace statue at the center of the park. But a small sign directs visitors to the sidewalk that departs from the north end, through a middle-class neighborhood, up the hill to the Catholic cathedral that bombardiers used to verify their positioning over the city that was for nearly 400 years the home of Japanese Christianity.

The previous day, we had visited the city of Kagoshima, farther to the south on the Japanese island of Kyushu. It was there that St. Francis Xavier landed 465 years ago this week, in 1549, fashioning himself as an apostolic nuncio to the emperor of Japan. He had studied with Ignatius of Loyola in Paris, and as one of the founding Jesuits, elected to leave his academic career for the life of a missionary. The clan that welcomed St. Francis became suspicious of the colonizing ambitions of the Portuguese missionaries that followed him, and Christianity established a more secure foothold to the north in the more internationally facing port of Nagasaki.

The growth of Catholicism for 80 years was punctuated by resistance from local monks and the Shogun rulers. In 1597, three Japanese Jesuits, a group of Franciscan missionaries, three boys and 14 Japanese men in the Third Order of St. Francis (of Assisi) were crucified on a hillside in Nagasaki. The progressive persecution culminated in the Shimabara Rebellion by Christian peasants in 1637. They were defeated the following year by a force of more than 120,000 warriors. Christianity was outlawed and violently suppressed, and a period of national seclusion from European influence lasted nearly 250 years.

In the absence of priests, a secret system of worship unfolded that was not known publicly until the Europeans returned in the 1860s. About 30,000 Kakure Kirishitans ("hidden Christians") emerged from hiding as Japanese society liberalized under the Meiji Restoration. The Urakami Christians were widely exiled initially, but eventually, there was a restoration of religious freedom. In 1895, they began building a cathedral church looking across the city toward the Nishizaka hillside where the 26 martyrs had been crucified 300 years earlier.

Nagasaki was not on the early list of targets for the atomic bomb. The story is told of how Secretary of War Henry Stimson had taken his honeymoon decades earlier in the beautiful ancient Japanese capital of Kyoto, with its thousands of Buddhist and Shinto shrines. So he insistently removed Kyoto from the short list of targets, and Nagasaki was added to the list in its place. A fuel pump problem delayed the takeoff of the new, specially designed B-29 bomber that carried the world's first plutonium bomb toward southern Japan the morning of Aug. 9. The initially clear weather had clouded over the intended target of Kokura, 80 miles to the north. Nagasaki, too, was under cloud cover when the group of three B-29s arrived. Running low on fuel, the pilots considered turning back and dumping their payload in the sea. But a break in the clouds allowed visualization of the twin Romanesque towers of the cathedral, where a morning Mass had just begun. Completed only 20 years earlier, the largest church in East Asia and all the people inside were destroyed at 11:02 a.m. on Aug. 9, 1945.

As Fr. Emmanuel Charles McCarthy has said, one bomb did more damage in a matter of minutes to Japanese Christianity than had 400 years of intense persecution by the rulers of Japan. The event was very much in the news again this week, with the death of Theodore "Dutch" Van Kirk, the 93-year-old navigator and last surviving member of the Enola Gay crew that dropped the earlier uranium bomb on Hiroshima.

The reconstructed Urakami Church looks out across a densely populated neighborhood. Three statues damaged by the bombing sit in quiet testimony to the destruction there. The church has a quiet majesty, with large murals depicting the Stations of the Cross and colorful stained glass windows displaying scenes from the Gospels. When we inquired about the schedule of Masses, a sextant enthusiastically ushered me to a small chapel astride the main church, where two priests were saying Mass beneath an ornate altar that featured the charred remains of a statue of Mary, found in the rubble of the church the morning after the bombing.

It was the feast of St. Bonaventure, the famed theologian reportedly given his name (Italian for "good fortune") by St. Francis of Assisi after the boy survived a life-threatening illness. The two young priests, Fr. Kenichirou Nakano and Fr. Yukinori Kawabata, spoke the order of the Mass in solemn Japanese. But the familiar contours of the eucharistic prayer and the warm greeting following the Our Father served to emphasize how much we shared in common, across cultures and a history of old hostilities.

Afterward, Fr. Nakano met me outside the church to talk -- French was the language we shared. He gave me a prayer card that marked his ordination two years earlier, and we stood beside a statue of Pope John Paul II, who had come to this church in a show of solidarity during visits to Nagasaki and Hiroshima in 1981. We talked about the Gospel reading for that morning, the fearsome warning given by Jesus in Matthew 11:20 of a "day of judgment" upon the three Galilean towns of Bethsaida, Capernaum and Chorazin that Jesus loved so much.

Later, I found myself standing with my 14-year-old son in the Nagasaki Atom Bomb Museum, admiring an American photograph taken the day after the bombing. It depicted a barefooted boy of about the same age, carrying his infant brother on his back to a crematorium. The expression on his face is one of resoluteness, but also weariness of war and hope for the future. The message of Fr. Nakano was similarly one of hope that we saw projected by the many people we met and peaceful places we saw in Nagasaki. We found ourselves asking that eternal question: What does it take to learn the lessons of the past, and how can we as Catholics recognize our common humanity in a world so resistant to shedding its violent instincts?

[Dr. Patrick Whelan is a pediatric specialist in rheumatology at MassGeneral Hospital for Children and a lecturer in pediatrics at the University of Southern California and Harvard Medical School. He is a member of the National Catholic Reporter's board of directors.]