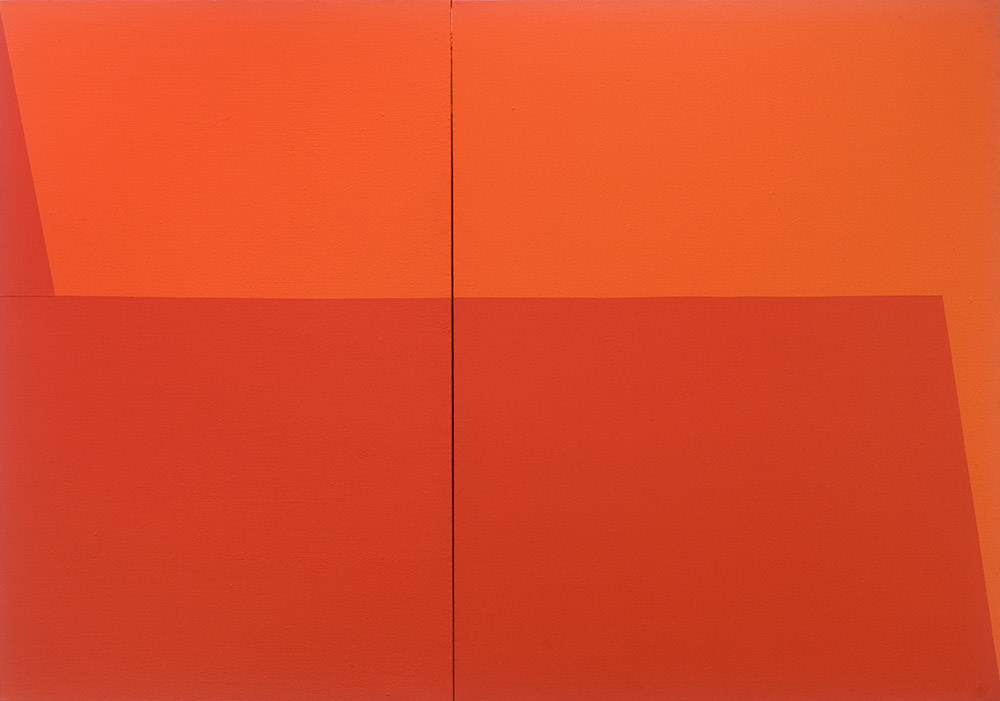

"Estructura Roja," by Carmen Herrera, 1966/2012, automobile paint on plywood (Courtesy of Carmen Herrera)

On May 30 this year (according to her Cuban passport) or May 31 (according to her American passport), the revered painter Carmen Herrera turned 105. To celebrate the birthday, El Museo del Barrio in East Harlem, New York, organized a Zoom celebration May 27 that Herrera had hoped to join — but finally decided to watch at home.

El Museo was a perfect host, with curator Susanna Temkin leading the conversation among Carolina Ponce de León, who had curated a major exhibition of Herrera's work at El Museo in 1998; Monica Espinel, who contributed the chronology to the catalogue of the Whitney Museum of American Art's landmark survey of her work in 2016; and Tony Bechara, an artist who has been a friend of Herrera's for decades.

Herrera was born in 1915 in Havana, the youngest of the seven children of Antonio and Carmela Herrera, who were both members of the city's intellectual elite. Although she studied architecture at the University of Havana for only one academic year in 1938, she was deeply influenced by the experience. ("I wouldn't paint the way I do if I hadn't gone to architecture school," she later said. "That's where I learned to think abstractly and to draw like an architect.")

But her previous study at the Lyceum, a cosmopolitan women's club in Havana, where she became close to the intrepid painter Amelia Peláez (her senior by almost 20 years), drew her back to painting and sculpture. In 1937, through her brother Addison, she met an American tourist, Jesse Loewenthal, whom she married in 1939 and with whom she moved to New York that year.

Loewenthal was a remarkably gifted and cultured man and with him Herrera became friendly with a wide range of New Yorkers, including Barnett Newman and his wife Annalee. She frequented the Whitney (where only Stuart Davis and Georgia O'Keeffe really appealed to her) and took classes at the Art Students League.

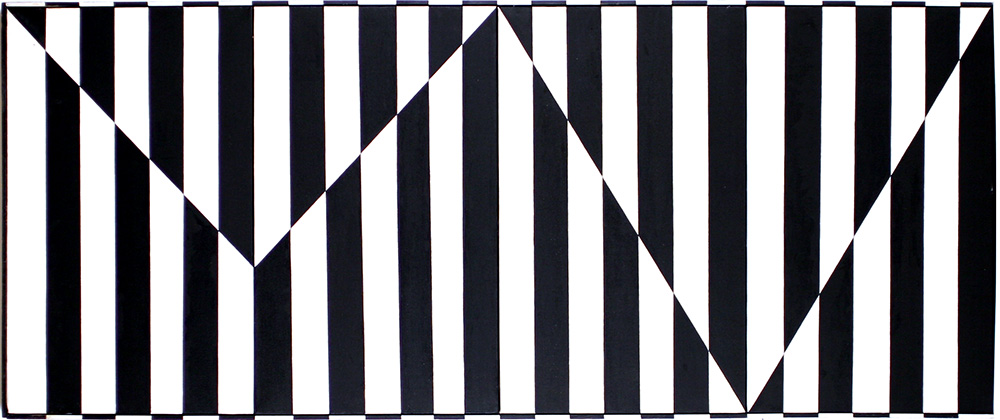

But she felt culturally adrift and was only too glad to move with Jesse to Paris in 1948, where she quickly set up a studio in their apartment. Socializing with the likes of Jean Genet and delighting in a city filled in the postwar years with other American artists, she happened on the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles, exhibited with it, and through it discovered the Bauhaus and Russian Suprematism. Thrilled, she began to move beyond experiments based on her academic training in Havana and New York and toward serious abstraction — at first organic or gestural but then increasingly geometric (a prominent example being "Black and White," from 1952). Finding acrylic more manageable than oil, she used it from then on.

"Untitled," by Carmen Herrera, 1952, acrylic on canvas (Courtesy of Carmen Herrera)

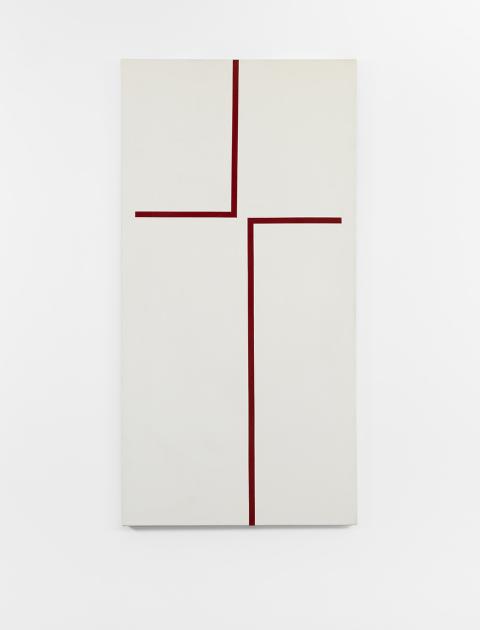

Returning to New York with Jesse in early 1954 for financial reasons, she continued the black and white paintings she had begun in 1952 — not so much a series as such but rather occasional step-backs from color to a purified simplicity she called "depuración" (purification). ("I had to forget about trimmings and go to the core of things," she said.) In the important exhibition many years later in 1998 at El Museo del Barrio, "The Black and White Paintings: 1951-1989," curator Carolina Ponce de León showed them in all their stunning originality. The earlier paintings were variations on a theme of primal tri-angular black forms emerging from (not in) a field of white that was inspired by the Neo-Plasticism of Piet Mondrian but risked unmooring his elegant harmonies with slashing diagonal lines. Later came formidable structures of black and white such as "Ávila" and "Escorial" (both 1974) inspired by the great Spanish painter Francisco de Zurbarán and the letters of Teresa of Ávila in the first case and by the architect of the Escorial, Juan de Herrera, in the second. (That show, she has said, was her favorite.)

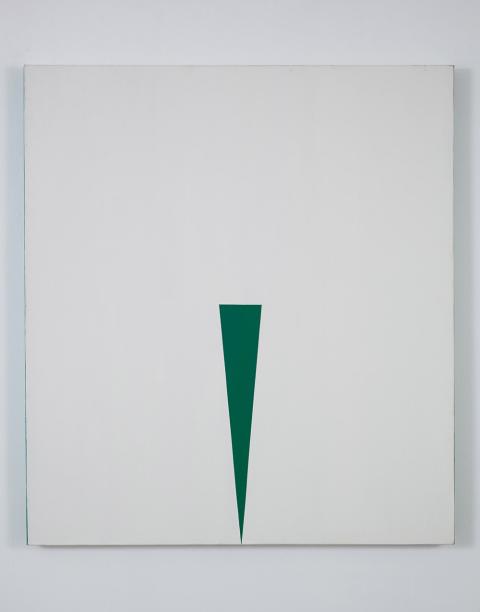

In the 1950s in New York Herrera had her first solo exhibition but due to the political turmoil in Cuba she did not exhibit between 1958 and 1962. Always politically conscious (though keeping politics out of her painting), she and Jesse became seriously committed to the cause of refugees fleeing Cuba. Nevertheless, she produced major works such as "Green and Orange" (1958), a large, angular interlocking of the two colors that looks more and more like a masterpiece, and "Equation" (1958), two large white triangles crowding four slender black ones almost out of the frame — one of her own personal favorites. Perhaps most important was her first painting in 1959 in the "Blanco y Verde" series that would continue for 12 years and for all their apparent minimalism reveal the sculptural instinct of her work. (The New York Times art critic Hilton Kramer called one work in the series, "Blanco y Verde" from 1967, "the best picture she has yet exhibited.")

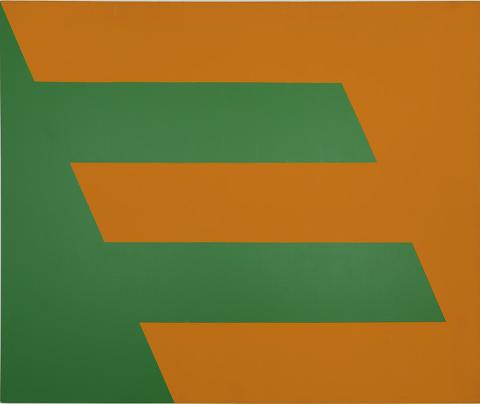

Supported by a fellowship from the CINTAS Foundation in 1968, Herrera began her series of "Estructuras," monumental structures — first made with fiberboard, Styrofoam and epoxy and later with wood — that included the biplanar, blue "Untitled" (1971) and the handsome, Chinese red "Estructura Roja" (1966/2012). (They were later shown in a solo exhibition in 1979.)

During the same period she continued to produce elegantly simple paintings such as "The Way" (1970), another masterwork of tensive, simplified precision in which two red-brown, thin angular forms attract and repel each other with seemingly boundless energy and balance. A final marvelous series on the days of the week — it would be the artist's last full series--was completed between 1975 and 1978, each painting with a large, irregular black form encroached on by vibrant dark blue, golden yellow, green, pale yellow, salmon and red forms, respectively.

In 1984 Herrera had her first retrospective at the Alternative Museum in New York. She was one of the artists responding to the AIDS crisis and painted "La Hora" and "Yesterday" in 1987 in honor of two friends who died of the disease. (Each is a black painting with a white line electrically zig-zagging through it.)

In 1988 one critic described her work in a solo exhibition at the Rastovski Gallery in New York as "a particularly sexy sort of geometric symmetry." (As with similar comments about her "Blanco y Verde" series, she was not impressed.) In the same year she was included in a survey exhibition on Latin American art, and a critic wrote in the journal "Contemporanea.": "Nothing can prepare one for the power and authority of Carmen Herrera's 'Green and Orange (1958).' …This spectacular work challenges one to imagine it in its proper context three decades ago."

With the 1998 exhibition at El Museo, the artist's slowly emerging reputation took a decided step forward. ("She occupies an honorable place in postwar geometric painting," wrote Holland Cotter in The New York Times, "and this fine show should help to secure it.")

In 2000, however, Jesse Loewenthal died at the age of 98, and Herrera was deeply stricken. Then in 2005 "Carmen Herrera: Five Decades of Painting" was held at LatinCollector in Tribeca and glowingly reviewed in the Times by Grace Glueck, whose appreciation for the architectural character of the work was, Herrera thought, the best she had read. She began to paint seriously again.

A video and a documentary had just been made about her, and her work began to enter the collections of major museums — the Tate in London, the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Museum of Fine Arts Boston and the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. In 2015 Alison Klayman directed a short, widely seen documentary about her, "The 100 Years Show," and in 2016 the Whitney presented the landmark "Carmen Herrera: Lines of Sight." Organized to explore the origins and development of her signature style of dichromatic, strictly geometric canvases between 1948 and 1978, it was brilliantly curated by Dana Miller, who also edited the handsome catalogue. (Included there is a fine chronology by Monica Espinel.) The exhibition placed Herrera, in Miller's words, "firmly in the pantheon of great postwar abstract painters alongside the likes of Ellsworth Kelly, Agnes Martin, Barnett Newman, Ad Reinhardt and Frank Stella."

And now, at 105, she continues to draw each morning in the apartment on East 19th Street where she has lived since 1967, not far from her beloved Church of the Epiphany. In 2019 the Public Art Fund presented her "Estructuras Monumentales," now rendered in aluminum, at City Hall Park in New York — outdoors and stunning. According to reporting by ARTnews, this year, working with the firm Publicolor, a not-for-profit that works with more disadvantaged public schools, she designed another outdoor artwork in East Harlem; more recently, again with Publicolor, she designed a 54-foot-wide mural entitled "Uno Dos Tres," based on her 1987 painting "Diagonal." As ARTnews reports, "The piece will go on view at Manhattan East School for Arts and Academics in New York, whose students helped complete the project."

"Red on Red (Rojo sobre Rojo)," by Carmen Herrera, 1959, oil and acrylic on canvas (Courtesy of Carmen Herrera)

For years the story was told that Herrera did not sell her first painting until she was 89. (In her chronology for the Whitney Show, Monica Espinel tells us that she actually sold three paintings to American tourists in Cuba when she was 20.) But at Sotheby's on March 1, 2019, her "Blanco y Verde" (1966-67) fetched $2.9 million.

Still, in her introduction to the catalogue for the Whitney show, Dana Miller quotes Herrera: "People keep saying, 'How do you work all these years without any reward, no money, and few exhibitions?' Because it was a vocation," she said. "Why would anyone go to a hospital to take care of the lepers if they do not have the vocation of being nuns? It's the same."

"Herrera has said that she did not choose to become an artist," Miller continued, "rather that she was chosen; she likened it to falling in love or being struck by lightning. And on more than one occasion she has even remarked, usually with a sly smile, that she herself should have been a nun."

The artist was marvelously independent from the start. When her friend Tony Bechara asked her how she had lived to be 100 and yet keep working, as we heard at the El Museo celebration, she told him: "For 100 years, you drink scotch and eat red meat. Then when you hit 100, you become a vegetarian and you drink champagne."

Felicidades, Sra. Herrera!

[Jesuit Fr. Leo O'Donovan is president emeritus of Georgetown University in Washington, and currently director of mission, Jesuit Refugee Service/USA. He is a frequent commentator on the arts for NCR.]

Advertisement