(Pixabay/StockSnap)

Early in The Body Artist by Don DeLillo, Lauren Hartke eats breakfast with her husband, Rey Robles, a Spanish-born film director. To say that they eat together would be imprecise; they exist in the same space — a rented home with the coastal sky in sight — but they speak past and around each other. Rey eats a fig, and the author describes the consumption as a performance: he bites off the stem, splits it open with his thumbnails and scoops "a measure of claret flesh out of the gaping fig skin. He dropped this stuff on his toast — the flesh, the mash, the pulp — and then spread it with the bottom of the spoon, blood-buttery swirls that popped with seedlife."

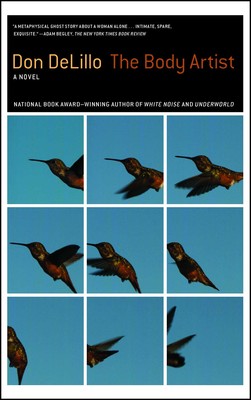

Published 20 years ago this February, the short novel is the type of work called "slim" by reviewers, a way to cast it aside from DeLillo's oeuvre. His first work following the sprawling Underworld, the book begins a sequence of mostly short texts, including The Silence, his most recent novel. Yet The Body Artist deserves to be more than a footnote to DeLillo's career; it is a moving, at times exquisite book about the strangeness of grief — a uniquely apt novel for our protracted moment of collective sadness.

DeLillo has said that he cares about "the construction of sentences and the juxtaposition of words — not just how they sound or what they mean, but even what they look like." A theology of typography, perhaps, for a Jesuit-schooled Bronx kid raised on Latin Mass, its grand performance a contrast with the Sicilian folk-belief in his immigrant home. No wonder he sees the sacral possibilities of syntax.

Elusive about most personal things, DeLillo has been famously coy when discussing his inspirations — except for his first novel, Americana. He was sailing in Maine and stopped at Mount Desert Island. There he "had a glimpse of a street maybe fifty yards away and a sense of beautiful old houses and rows of elms and maples and a stillness and wistfulness — the street seemed to carry its own built-in longing." Beneath his ironic and sometimes cynical sheen, DeLillo has a sentimental core — and that emotion comes through in his reverence for language: a Catholic liturgy without belief.

This absence permeates The Body Artist. After the initial breakfast scene, we learn that Rey dies by suicide. DeLillo has always had a discarnate style with his characters; in novels like End Zone and Point Omega, his people are spirits and specters. In the first scene after her husband's death, Lauren is driving on "a hazy white day" as the "highway lifts to a drained sky." DeLillo shifts to an almost disembodied second-person narration. At the top of the hill, "the cars begin to move unhurriedly now, seemingly self-propelled, coasting smoothly on the level surface. Everything is slow and hazy and drained and it all happens around the word seem. All the cars including yours seem to flow in a dissociated motion, giving the impression of or presenting the appearance of, and the highway runs in a white hum. Then the mood passes. The noise and rush and blur are back and you slide into your life again, feeling the painful weight in your chest."

"The plan was to organize time until she could live again," Lauren decides — a sentiment that feels so piercing now as we drift through a perpetual present.

The scene previews the fragmentation of Lauren's body and soul, a finely tuned representation of grief. "Now he was the smoke, Rey was," DeLillo writes, "the thing in the air, vaporous, drifting into every space sooner or later, unshaped, but with a face that was somehow part of the presence, specific to the prowling man." She senses him with her in the empty house. All attempts to distract herself fail. She talks on the phone to her friend Mariella, a writer in New York. Mariella asks: "But are you lonely?" Lauren answers: "There ought to be another word for it. Everyone's lonely. This is something else."

Then, she hears a noise, almost a kind of poltergeist. The next day she discovers a man: "He was smallish and fine-bodied and at first she thought he was a kid, sandy-haired and roused from deep sleep, or medicated maybe. He sat on the edge of the bed in his underwear." At first, he seems to be a spirit: "He moved uneasily in space, indoors or out, as if the air had bends and warps. She watched him sidle into the house, walking with a slight shuffle." Lauren feels more fascination than fear.

Is she hallucinating? DeLillo is not concerned with the psychology behind this; a mysterious man Lauren loved is gone, and the world must fill his absence. Lauren's performance artistry requires constant attention to her own body. She uses sand and pumice stone on her skin and passes the time through breathing and poses and stretches as if she wants to so fully exist in the flesh that she can contrast with Rey's memory and this ghost of a man who dwells in the house with her. She shares days and days with him, but he gives her no clear answers about death. Instead, she arrives at a strange transcendence: "If there is no sequential order except for what we engender to make us safe in the world, then maybe it is possible, what, to cross from one nameless state to another, except that it clearly isn't."

Advertisement

"The plan was to organize time until she could live again," Lauren decides — a sentiment that feels so piercing now as we drift through a perpetual present.

A year into the pandemic, there is no past and no future: There is a permanent now — a waiting. We don't need to call DeLillo a prophet; his prescience is for the human condition, not seeing into the future. Twenty years later, The Body Artist feels not merely relevant, but essential: a book about drifting with grief as if it were wind: a rush that "strips you of assurances, working into you, continuous, making you feel the hidden thinness of everything around you, all the solid stuff of a hundred undertakings — the barest makeshift flimsy."