People from the Campion Propaganda Commitee, a Catholic organization, protest religious persecution and the oppression of Jews in Germany in front of the German Consulate in New York in 1936. (Newscom/AKG-Image)

The recent Broadway production of "Network," starring acclaimed actor Bryan Cranston, seems like a perfect fit for our political moment. The play — based on the Oscar-winning 1976 movie — explores how rage has seeped into every crevice of our lives.

Yet more than four decades before Paddy Chayefsky's famed screenplay hit theaters, a 20-year-old from the waterfront slums of New Jersey was coping with his own political anger.

During the broiling summer of 1935, Bill Bailey was mad as hell. And he didn't want to take it anymore. "It was time now to do something to wake this goddamn United States up," Bailey once said.

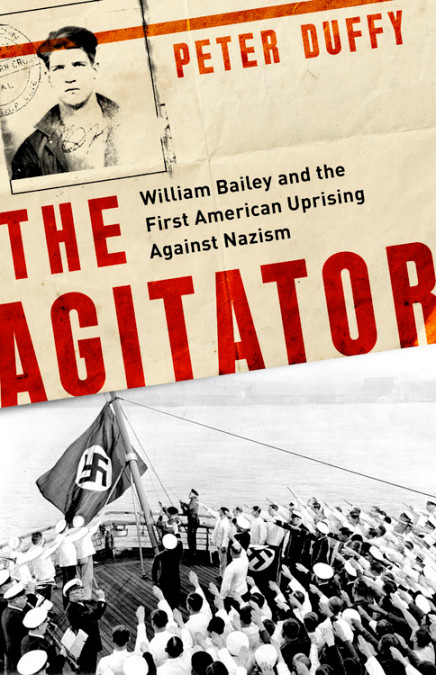

That "something" is at the center of Peter Duffy's absorbing history, a page-turner packed with colorful characters and events. But as a broader portrait of an angry, complex era — not unlike our own — The Agitator raises more questions than it answers.

On July 26, 1935, Bailey — the son of Irish immigrants — and a band of proud union- and communist-affiliated pals boarded the SS Bremen, docked on New York's West Side. The state-of-the-art ship was a floating testament, in the eyes of Hitler's Nazi regime, to the superiority of the Aryan race.

Bailey and his crew planned to — and succeeded in — tearing down the Bremen's giant swastika flag and heaving it into the Hudson River.

The action "precipitated a diplomatic controversy that engaged the highest levels of the American and Nazi governments," writes Duffy, who adds that Bailey and the other members of the so-called "Bremen Six" had "issued a call to action."

Duffy convincingly argues that the ugliest portions of the Nazi plan were already clear by 1935, including the extermination of European Jewry.

Germany had also detained an American seaman named Lawrence Simpson on charges of spreading communist propaganda and targeted other minorities, including Catholics.

"Although the Hitler state had negotiated the Reichskonkordat with the Vatican in July 1933, permitting Catholic clergy to continue worship practices as long as they stayed out of politics," writes Duffy, "the Nazis were deeply suspicious of a foreign-led institution that didn't regard Adolf Hitler as the one true god."

Advertisement

Duffy's exploration of Nazi Germany and Catholics — on both sides of the Atlantic — is refreshingly nuanced.

"Communist canvassers fanned out to Catholic churches in New York to distribute a mimeographed handout ('Protest Nazi Terror! Unite Against Fascism!')," Duffy writes. That this coalition-building was rooted in political expediency makes it no less interesting. Catholics were asked to join Jews, communists and anti-fascists to protest the Bremen's presence in New York. "A large and successful meeting on the pier will help your brother Catholics in Germany," a handout read.

This all culminates in the semi-comic, semi-surreal images of the lapsed Bailey decorating himself in rosary beads on the night of the Bremen operation, in the hopes that the mostly Irish NYPD would go easy on him, once they saw he was not Jewish.

But while the execution of the Bremen operation, Bailey's arrest and the subsequent circus-like trial are told dramatically, The Agitator lacks important historical context. When considering why America was reluctant to confront Hitler, Duffy tends to cite timidity at the federal level. But legitimate questions remained about why the U.S. had bothered to intervene in the First World War less than two decades earlier.

Then there is the very diversity for which New York is so often celebrated. Manhattan's Upper East Side was heavily German, and Duffy notes that the area where the Bremen docked "was a tiny province of the Third Reich." Italian Americans, meanwhile, had their own mixed feelings about dictators and fascism.

As for all those Irish cops, many were also, like Bailey, "brought up in the Irish tradition that celebrated the far-sighted few who mounted audacious risings to bestir the unenlightened many," yet did not generally share Bailey's leftist sentiments. Why not? Why did they prefer to act (in an unfortunate phrase Duffy borrows from Bailey's era) as "Tammany Cossacks"?

An unspoken assumption here seems to be that if the U.S. had simply built a wall, say, circa 1900, Hitler might have been confronted sooner.

Meanwhile, marketing this book as an "inspiration to anyone who seeks to resist tyranny" leads to additional unsettling questions. Without dabbling in the kind of dimwitted sophistry beloved by many in the Trump era, it is fair to ask: Who defines tyranny? And what kind of action effectively resists it?

In hindsight, Nazi Germany certainly should have been confronted sooner. What about communist Vietnam? Ortega's Nicaragua? Saddam Hussein's Iraq? Assad's Syria?

In the end, as principled as Bailey's convictions were, it could be argued the Bremen operation had the opposite intended effect. By the mid-1930s, several German American organizations were merging to form the notorious Nazi-friendly Bund organization, which Duffy does not mention.

Fr. Charles Coughlin (also not mentioned) was on his way to becoming an anti-communist, anti-Semitic hero to rural Protestants as well as to urban Catholics, the latter of whom filled the ranks of the (also notorious, also not mentioned) Christian Front.

Like Bailey, these folks were also mad as hell. And they, too, did something about it.

[Tom Deignan, a contributor to the recent book Nine Irish Lives, has written about books for The New York Times, The Washington Post and Philadelphia Inquirer.]