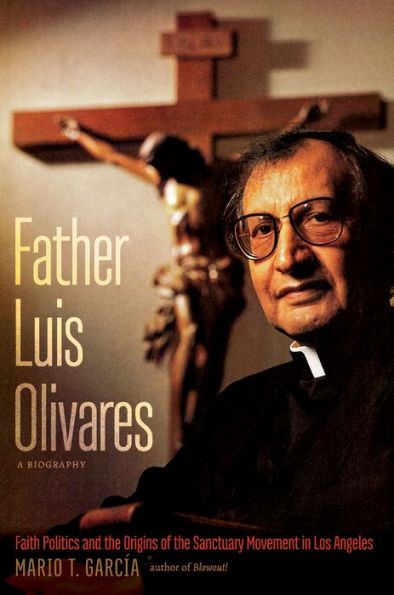

Claretian Fr. Luis Olivares is arrested in front of the federal building in downtown Los Angeles on Nov. 22, 1989, as demonstrators blocked the entrance during a protest against U.S. policy in El Salvador. (AP/Nick Ut)

Claretian Fr. Luis Olivares, the subject and title of the recent biography by Professor Mario García of the University of California, Santa Barbara, was the major force in the sanctuary movement in Los Angeles. Using the oral history of those who knew Olivares, García describes the immigration of the Olivares family, religious people who dared hide priests during the Mexican Revolution but finally were forced to flee to the United States and settle in San Antonio, where Luis Olivares was born.

We are invited into Olivares' youth on the Mexican American west side of segregated San Antonio. Olivares felt the call of the priesthood from a very early age. He served as an altar boy, studied the priesthood, memorized the liturgy in Latin and often played the role of a priest while other boys played sports.

In 1948, a year after his older brother, Henry, entered the Claretian seminary in Compton, California, 13-year-old Luis followed. García gives a detailed description of seminary life in those days and speculates that the deliberate isolation of young boys from their families to make the Claretian order their new family might well be a kind of abuse.

Soon after ordination, Olivares became the treasurer of the western province of the Claretians. As treasurer, he decided, with the board's approval, where to invest large sums of money and oversaw the budgets of local parishes.

As he had regular meetings with fund managers, investment counselors and bankers, he dressed well and drove expensive cars to fit in. He acquired the nickname of the Gucci Priest. García paints a picture of a young priest who, despite his vows of poverty, enjoyed flying to New York or Washington, D.C., going to Broadway shows on comps, and being wined and dined.

The Gucci Priest was ambitious, and to beef up his résumé he took the position of pastor at Our Lady of La Soledad Church in the largely Mexican American east side of Los Angeles, while still remaining treasurer of his order.

His new position put him in contact with those who managed without large sums of money. Olivares had never before shown much interest in liberation theology. He knew about it, of course, and sympathized with it and with Vatican II, but he was much more aligned with the traditionalists. Still, he gave Mass in the vernacular, in English and Spanish, while facing the congregants. Not blind to the subtle and not-so-subtle discrimination against Mexican Americans in his hometown, at the seminary and beyond, Olivares got in touch with his roots. At La Soledad, "history caught up with him."

As treasurer, he met César Chávez. As pastor, he became active with the United Farm Workers. He and Chávez became lifelong friends, and Olivares became the UFW's principal contact in Los Angeles. Olivares participated in bargaining sessions, meetings with politicians, and strikes. He became an active member of the community and efforts to organize. He became a leader of the United Neighborhoods Organization that successfully fought redlining of the Mexican American community by the powerful auto insurance industry, a campaign that brought him even more renown and admiration.

In 1981, Olivares became pastor of Our Lady Queen of Angels Church, affectionately called La Placita. La Placita is a small church, but of great historical significance in Los Angeles. It had an impressively large congregation, perhaps 100,000 families in the 1980s, with 10,000 to 12,000 people attending 11 Sunday Masses, as well as a large staff to serve the congregation.

At La Placita, the conversion of Olivares became complete. He long admired Monseñor Óscar Romero, who was murdered by a death squad in 1980. Olivares possibly saw parallels with his own life. Romero was conservative when appointed archbishop of San Salvador, El Salvador, but he could not close his eyes to the suffering of the poor, especially after his friend, Fr. Rutilio Grande, was assassinated by a death squad.

Like Romero, Olivares grew to embrace liberation theology and the preferential option for the poor, as opposed to the traditionalist approach of the church taking priority. Olivares began to not only advocate for Central American refugees, but offered them food and shelter, clothing, medical care and employment services. As the terrible wars continued, the number of refugees increased and soon La Placita's basement and even the church pews filled with men needing shelter for the night — women were given shelter at Casa Rutilio Grande. Olivares worked with Jesuit Fr. Mike Kennedy, who oversaw the shelters, food and employment projects.

Soon, La Placita sheltered hundreds of homeless and refugees every night, an astounding and praiseworthy phenomenon. Some local businesspeople and conservatives complained about the mass of people in the neighborhood, but Olivares, as García never tires of informing us, was charismatic and had great leadership qualities, and he did what he thought was right. Liberation theology had come to La Placita.

Advertisement

In 1985, after years of giving shelter and other services to refugees, Olivares publicly declared sanctuary. Media-savvy, he invited the press, his Hollywood friends, Chávez, the provincial of the Claretians and Los Angeles Archbishop Roger Mahony. Disappointingly, the archbishop failed to show, after telling Olivares he would be there, but he sent an auxiliary bishop. Catholic bishops were opposed to sanctuary because they did not want to antagonize the Reagan administration, but to Mahony's credit, he did nothing to stop Olivares.

Giving shelter to so many likely put Olivares and La Placita on the radar of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, and probably the FBI. Declaring sanctuary carried risks.

Declaring sanctuary was a political act, an act of defiance to the federal government and especially to the INS. While the terrible wars in Central America continued unabated, the public relations war in the United States heated up. As the sanctuary movement grew and stories of the refugees were publicized, the movement became a threat to the Reagan administration.

In order to continue funding for the Guatemalan military, President Ronald Reagan signed white papers swearing that the human rights situation in that country was improving. He even famously stated that a Guatemalan military dictator was getting "a bad rap" on human rights — this at the height of the most recent genocide in the Americas.

When two reporters broke the story of the Atlacatl Battalion's massacre of hundreds of civilians in 1981 in the insignificant Salvadoran town of El Mozote, a massacre that took all day because there were so many men, women and children to kill and so many women and young girls to rape, the reports were vilified, denied or called wildly exaggerated.

Luis Olivares in San Bernardino, California, in 1979 (NCR photo/Bill Kenkelen)

At the sanctuary trial in Tucson, Arizona, the court forbade the defendants from referring to the atrocities in Central America, U.S. foreign policy, international law regarding refugees, bias in the asylum process, or even the defendants' religious beliefs.

Olivares became a media star. He was invited to speak at many demonstrations. He went on delegations to Central America. He was on the radio and television and in newspapers and magazines. He actively assisted refugees, undocumented Mexicans, the homeless and unions. When the U.S.-trained Atlacatl Battalion murdered six Jesuit priests, their housekeeper and her teenage daughter at the University of Central America in San Salvador, Olivares, along with many others, was arrested at a mass protest that closed access to the Federal Building in downtown Los Angeles.

Olivares came to admire and respect rebel movements in other countries, and he became a rebel himself in his embrace of liberation theology and the preferential option for the poor. He declared, "If it is expected for the Church's survival to align itself with the rich and the powerful, I'd go so far as to say that the Church should not survive." He called for evangelization based on the Gospel.

Becoming a public figure and a rebel had its drawbacks, and he received death threats. The threats were particularly intimidating because Central American death squads had been implicated in the kidnapping, beating and torturing of activists in the Los Angeles area. Olivares continued offering sanctuary.

When reading Father Luis Olivares, it's hard not to notice a number of typographical errors, a few malapropisms and a good deal of repetition. I blame the publisher, the University of Carolina Press, for slipshod editing. I was not going to mention the errors, thinking it too petty in a work about a man whose actions merit the utmost respect and approval, but the errors went on and on.

The final chapters about Olivares becoming a liberation theologian were most compelling and the chapter about his illness and death from AIDS was quite moving. However, I question the way García deals with the AIDS issue.

At that time, AIDS carried a terrible stigma and was thought of as a gay disease. García repeats that Olivares and those close to him decided to go public with Olivares' story that he had AIDS and to say that he contracted it from a dirty needle in El Salvador to get ahead of any attempts to smear the sanctuary movement. García is guilty of either coyness or clumsy writing. He uses terms such as "the official version," "the story," "the El Salvador account" and "it was important to tell the account he had already told others." This caused me to wonder if he had his doubts about "the story."

In the body of the biography, the only mention of Olivares' sexuality is his denial that he is a homosexual when interviewed by a reporter from the Los Angeles Times. In the epilogue, García writes that Olivares had human failings, as do we all, and "struggled with his vows of chastity and celibacy like all priests." This is a curious statement standing alone. García did a great deal of research and conducted many interviews, and gives great detail about much of Olivares' life, but nowhere does he discuss this "struggle."

What are we to think about García's approach to — and avoidance of — this issue? In the prologue, he states that he wrote this biography because he felt that Chicano students needed Chicano heroes. The Chicano students I work with are bright and inquisitive and will certainly wonder about García's handling of this issue. AIDS is a controversial subject, but homosexuality does not detract from heroism, as the church remains opposed to homosexual sex but not homosexuals.

Despite its faults, some amusing, some annoying, Father Luis Olivares, A Biography is a well-researched account of the life of a man who grew to an awakening, who witnessed the terrible reality of the times and acted according to the Gospel.

[Michael Smith is the refugee rights program director at the East Bay Sanctuary Covenant in Berkeley, California. Considered an expert on the treatment of indigenous peoples in Guatemala, especially during the Guatemalan Civil War, he has received awards for his work with refugees from Helen Bamber and the Dalai Lama.]