(Unsplash/Chris Orcutt)

D.L. Mayfield is a prophet constantly traveling a path of conversion. From white evangelical homeschooled girl, to Bible-college grad gearing up to go on mission to convert people to Christ, to downwardly mobile neighbor of Muslim Somali Bantu refugees, she finds that God has a funny way of challenging her drive to "convince people of the rightness of her cause."

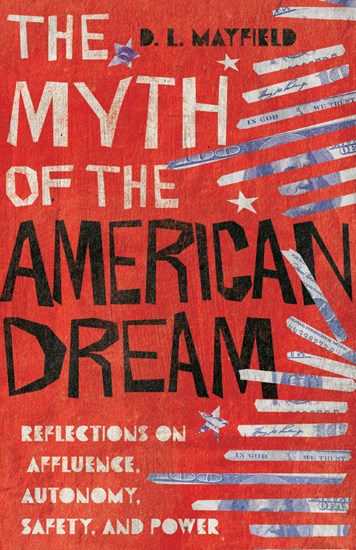

Her latest book presents itself as a critique of the American dream when, in reality, it is more of a personal confession — a Christian's painstaking attempt to sort out the privileges and false idols that were embedded in her formation. The Myth of the American Dream's exhortations to convert our hearts and social structures are compelling, less because of Mayfield's use of Scripture and statistics, but more so because of her sincere personal witness and lived example.

Her sincerity considered, Mayfield does come off as moralistic and preachy at times. She harps on the moral faux pas of evangelical leaders, (as of this fall, she no longer identifies with the label "evangelical" because of its ties to "Christian nationalism"), and will never let herself, nor any other person of privilege, off the hook. But even what can be perceived as virtue signaling is convincing.

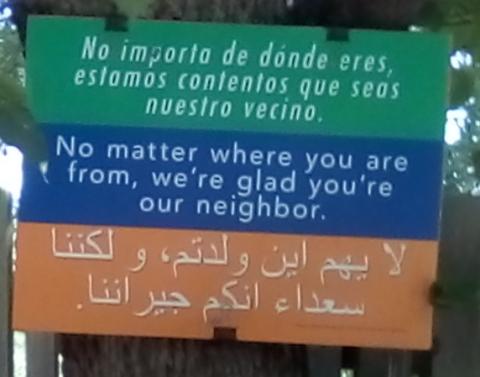

Take her decision to display one of those ubiquitous "No Matter Where You're From, We're Glad You're Our Neighbor" signs. "I wanted to love others in a way that is easy and still makes me feel good," she admits. "I'm the type of person who loves to display my values on a sign in front of my house — a house I could afford to buy in part because of my privileged position in society." After a few months, the sign was intentionally run over. She put it back in its place, feeling "proud of her tolerance" and "a grim satisfaction," only for it to be stolen a few days later.

She uses this anecdote to launch into a historical evaluation of white flight, generational poverty, and the phenomenon of immigrant and refugee families being unable to afford rental prices in the city and having to rent from unwelcoming homeowners in the suburbs. This evaluation seamlessly weaves more stories of personal encounters, scriptural passages and introspective reflections, crafting a beautifully compelling and thought-provoking tapestry.

She is left in tears after her Muslim refugee neighbor tells her about being spat on by a man who yelled at her to "go back home." But instead of weeping, her friend told her plainly, "Allah plants both good and bad plants in every country of the world … you cannot have a world with just one kind." Besides, she said laughing, even the Virgin Mary wore a headscarf. Why did he see her hijab to be such a threat?

(Wikimedia Commons/Earlyspatz)

At a neighborhood association meeting, a white homeowner asked a police officer how they were going to "take care of the bad guys" moving into the neighborhood, as she held her fingers out in the shape of a pistol. "How do you love your neighbors when some of them have had fear curdle their hearts, when violence appears to them the best solution?"

She comes back to the lawn sign, questioning whether her intentions were merely a selfish attempt to quell her white guilt. But after a brief conversation with a non-white neighbor, she's reminded that the true value of the sign had less to do with her virtuousness and more to do with the needs of her neighbors. "Did you take the sign down?" he asked. "As soon as you put it up, I know I could trust you."

This tapestry, as well as those found in the other chapters that follow a similar pattern, reveals what's so unique about Mayfield's critique of the American dream. It's characterized by her proximity to the people who are implicated in the issues she addresses, or what she would say is her determination to live out the call to radical "neighborliness." Her critiques come not from above, but from living in communion with the people she writes about — both the oppressed and the oppressor, the "woke" and the ignorant — all of whom she regards as current or potential neighbors.

This call to radical neighborliness is rooted in her reading of Scripture, namely the distinction she finds between Isaiah 61 and Luke 4. Whereas Isaiah is told to proclaim "the years of the Lord's favor and the vengeance of our God," Jesus reads this verse in the synagogue, leaving out the part about God's vengeance, stating "today this Scripture has been fulfilled."

"In the space of a few verses, everything changes," she writes. Jesus "was not just on the side of the chosen few but had swung wide the gates of love." God's favor is as much for the righteous as it is for the "other" — whether that other be the refugee, the poor, the sinner or even the oppressor. As much as the oppressor may be in the wrong, and their "toxic narrative and unequal power" ought to be corrected, we are called not to be victorious over them, but to enter into communion with them.

Her living out of the call to neighborliness is bolstered by the practices of "curiosity" and "lament." Those who are more privileged than others are prone to the "amnesia of affluence," which blinds them to the "vastly unequal economic world" they benefit so much from at the cost of others' well-being. People who are economically well-off and live in affluent neighborhoods are often afraid to talk about money, she claims. The more they question how they acquired their money and how their neighborhoods got to be so well-to-do, the more likely it will be revealed that, along the way, someone or some community is unjustly suffering so that they can maintain their wealth and comfort. Throughout the book, she brings up the effects of redlining and gentrification, and how they enable the blindness and disconnectedness of the comfortable from the lived realities of the disadvantaged.

Advertisement

Mayfield recalls a time that Rani, a neighbor from Myanmar, gave her son $50 for his birthday. Shocked that a woman who struggles to pay her own bills offered such a generous gift, she told Rani to take it back, but Rani insisted. After days of stewing over her guilt for accepting the money, she was surprised once again when a beggar approached her and Rani asking for money, and Rani put $5 in his cup. "If you give money to people who need it, then when you are in trouble you will get money. Do you understand, Daniella?"

This is when Mayfield realized that her mentality was one of scarcity, whereas Rani's was one of generosity. "If I was listening to the Spirit, I would have followed Rani's example and given that $50 bill she shoved into my hand away to any person who asked. … But I didn't because shame has stunted my imagination from generosity." Rather than questioning how to respond to such a surprising gift, she deposited in the bank so as to "not have to think about it."

The more we ask questions about suffering and injustice, the more we recognize that everything is not as bright as people in power make it out to be. But we ought not allow the state of the world to lead us into despair or anger. Instead, she points us to the Hebrew prophets who opted to speak truth about injustice and infidelity, to live in "anguish and lament with the people." Lamentation of social injustice is "a sign of radical hope in a God who is listening."

Some may find Mayfield's prophetic witness to be unrealistic. Not everyone has the courage to take up the path of downward mobility — to opt out of living in safe, comfortable neighborhoods and sacrificing what's "best" for their kids for the sake of a more equitable social order. Then again, not everyone is called to be a Jeremiah or a John the Baptist.

Perhaps what's least realistic is her skepticism toward gestures of charity. The book is littered with critiques of Christians whose attempts to serve the underprivileged she deems to be inadequate for their lack of engagement with the systemic inequalities that created the need for charity in the first place. As much as we ought to question said systems, she often seems to equate sanctity with activism and the kingdom of God with a just socioeconomic system.

She speaks often of her esteem for Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker movement and even calls herself a Christian anarchist as Day did. But as much as Day was a harsh critic of structures of sin and systemic injustices, she generally deemed attempts to align the affairs of the state with the ideals of the kingdom to be futile. Her anarchism was rooted in an Augustinian suspicion toward the City of Man. Her activism focused less on engendering systemic socioeconomic changes and more so on creating alternative political and economic spaces, rooted in charity — that is, the sharing of life together — and ordered toward just relations with God and neighbor.

Though her "talk" may rely heavily on contemporary social justice activist jargon, Mayfield's "walk" — her lived witness of neighborliness — is a modern day example of the type of communal life that Day sought to foster through the Catholic Worker movement. This type of community in which she is willing to learn from and be corrected by her neighbors, lament and celebrate with them, reveals a vision of love and justice that points to a higher plane.

While there's room to debate the extent to which we ought to engage in political activism, you can't deny that the kind of unity, or shalom as she would call it, she is living with her neighbors is born not of a structure or system but of a heart full of love and a desire for the good.