People drum and dance in Congo Square, New Orleans, October 2011. (Wikimedia Commons/Bart Everson)

Not unlike the millennia of silt layers that created this crescent-shaped, flood-prone land mass 90 miles north of the Gulf of Mexico, la Nouvelle Orléans is a complex, multilayered cultural mosaic that is, perhaps, both plainly American and simultaneously its own class.

The complexity, triumph and tragedy of this "sliver by the river" is intimately intertwined with the fact that it is the "least-worst place" to build a city on a swamp, as the historian Ned Sublette explains.

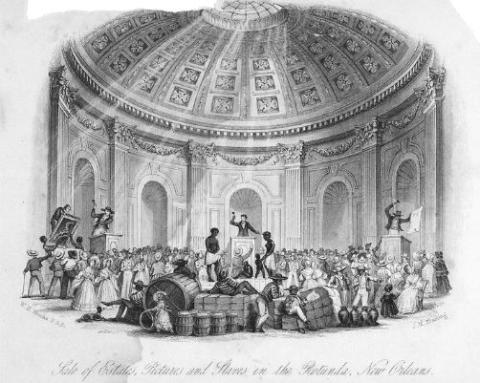

Too often forgotten, however, as tourists imbibe New Orleanian hospitality and charm, is the fact that the city is built upon backbreaking suffering and labor of Houmas, Chittimachas and enslaved Africans. How many visitors notice the historical markers of slavery in the French Quarter, including the original slave exchange at the corner of Chartres and St. Louis streets and the beautiful ironwork of enslaved Senegalese artisans?

City of a Million Dreams vividly remembers this brutal past and rightly commemorates both the insuppressible African struggle for freedom and irrepressible yearning for new life sung by every new stream of migrants.

Tomes have been written about individual events like Hurricane Katrina, but it is rare to find a single, inclusive history of New Orleans. To a student of this city's rich history and culture, it seems presumptuous to even attempt a history of its first 300 years.

Yet Jason Berry achieves the feat by writing with the humility and boldness his subject demands. Wisely, he does not attempt a comprehensive history.

Rather, with New Orleanian lagniappe, he directs a vibrant parade of the varyingly flamboyant, debauched, oppressive, corrupt, holy and unholy, and brilliant and idiotic characters who exemplify distinctive eras. He casts "this narrative as a character-driven history, training a viewfinder on selected people whose lives held a mirror to the changes in daily life."

Advertisement

Drawing upon the best scholarship in military and political history, culture, music, food, and urban geography, Berry's resources offer delightful insight into the vast mosaic that is this global city.

The book begins, appropriately, with the coincidence of two momentous occasions that capture both the resilience of New Orleans: its enduring tradition of practicing resurrection through the venerable "second line" and its endless obsession with the Lost Cause of the Confederacy.

As Mayor Mitch Landrieu led the jazz funeral for the great composer Allen Toussaint in 2015, alongside a grand musical celebration of the living legends of jazz, a furor erupted over the mayor's decision to remove the memorials to Confederate generals. The mayor and many of his supporters endured death threats throughout the ordeal.

These two events evoke the contradictory history of a city that is a crossroads of humanity caught between the grieving "tolling of dirges" that ushers the dead to their burial, and post-burial, erupts in joyous music and dancing that heralds the everlasting hope of resurrection.

New Orleanians perfected the art of parades over centuries. Funerals with military bands were commonplace as early as the memorial for King Carlos of Spain in 1789. Berry illustrates the initiation of carnival parades in 1857 and how Reconstruction-era Mardi Gras parades featured costumes "with scalding, often racist satire," often mocking Union generals and Northern "carpetbaggers."

Etching depicting "Sale of Estates, Pictures and Slaves in the Rotunda, New Orleans," 1853 (The New York Public Library)

Yet, as Louis Armstrong would later reflect on the street dancers of his early youth, "anyone can be a Second Liner whether they are Raggedy or dressed up. … They seem to have more fun than anybody. (They will start a free for all fight any minute.)"

Whether dancing or fighting, parading was how descendants of slaves asserted their freedom. Indeed, the carnival tradition of black men parading in feathered suits at Mardi Gras, as they chanted, "Don't bow down," memorializes the first Congo Square dancers who broke cultural barriers "with their unleashed body language."

Although the French Code Noir of 1724, drafted in Paris with advice from Jesuits who led plantation regimes, attempted to enforce Catholic culture by excluding Jews and to tame slavery by exempting slaves from work on Sundays, other practical realities took over. Jewish and many other migrants thrived anyway.

And while slave owners and priests relied heavily upon punishment to enforce slavery, they also allowed slaves to carry their own weapons, be entrepreneurial, work their own gardens, and to hunt, fish, trap and gather fruit to avoid the constant threat of famine. The place we now call Congo Square originally served as a marketplace where African peoples also "used the land to dramatize their past, resurrecting burial choreographies of the mother culture."

A 2015 Second Line parade in New Orleans (Flickr/VeryBusyPeople/Jason Wu)

New Orleanians are reminded of the rich multiracial, multiethnic and religious Creolization of the city every year on the last day of Essence Fest. The celebration of Maafa, a Kiswahili term for great disaster, gathers New Orleanians of African descent in Congo Square, beautifully adorned in white — the African color for memorializing the spirit — to remember, grieve and celebrate the lives of African slaves who congregated there on Sundays to sing, dance and create new forms of vocal and musical expression that grew to become the deep cultural roots of jazz and blues that echo throughout U.S. society today.

Berry recounts this pulsating history beautifully, including how Senegambians and other African peoples brought the city rice and okra, two indispensable staples of south Louisiana cuisine. While New Orleans is indisputably Catholic, African religious memory and practice, expressed through Gospel choirs or Haitian voodoo, lift spirits throughout the city.

This history is timely. As a white-nationalist president attempts to reclaim a racial purity that never existed, this city's complex historical crossroads of humanity reveals the lie of white supremacy. Although Berry's epilogue misses the significance of emerging Latinx neighborhoods and seems naive about the success of the charter-school movement, this is a history worth savoring. As we march into global transformations of the 21st century, we have much to learn from a City of a Million Dreams.

[Alex Mikulich is a Catholic social ethicist and New Orleanian since 2008.]