(Pixabay/PublicDomainPictures)

At pivotal points in its history, the church has stood squarely in the path of scientific inquiry in an attempt to block the way. This has never worked out well for the church. Whether it's Copernican theory or contraceptives, when faith runs afoul of scientific proof and personal experience, science and experience tend to win.

Many of us struggle to reconcile outdated tenets of a faith we love with the burgeoning scientific evidence about the world around us. In the new book Teilhard's Struggle: Embracing the Work of Evolution, St. Joseph Sr. Kathleen Duffy portrays French priest Teilhard de Chardin as the patron saint of this struggle.

Teilhard was a Jesuit priest and a gifted paleontologist who endeavored to reconcile the fossil evidence for Charles Darwin's theory of evolution with traditional Catholic theological teachings. His love of the Earth and geological excavations into its layers made it impossible for him to see creation as a one-time event.

This, and his mystical vision of cosmic spirit-matter integration, brought him into a lifetime of conflict with church authorities. He could not accept the lingering dualism in Catholicism that saw matter and spirit as separate.

Duffy uses a quote from his work The Divine Milieu to explain his views: "By means of all created things, without exception, the divine assails us, penetrates us, and moulds us. We imagined it as distant and inaccessible, whereas in fact we live steeped in its burning layers."

Duffy is a professor of physics at Chestnut Hill College in Philadelphia and is the author of several books on Teilhard. She is also a participant in efforts to have him named a doctor of the church. Her experience as a physicist, woman religious and teacher makes her an excellent guide for those of us who have hesitated to tackle Teilhard's works due to their complexity and unique language.

She begins by focusing on his major essay, "The Spiritual Power of Matter." This sets the stage for understanding his life's work — a struggle to find spiritual salvation by journeying into the heart of matter. In this essay, we learn of the mystical vision that set him in an intimate battle with matter, and the grappling that leads him to conclude that matter is alive, evolving and filled with the incarnate presence of God. He sees matter as encompassing all of the reality that surrounds us and he advises that we can be destroyed by it or learn to use it as the path to salvation.

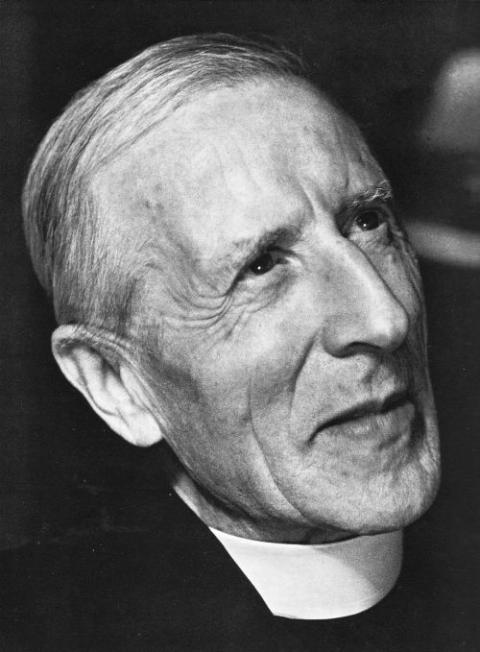

French Jesuit Fr. Teilhard de Chardin, 1947 (CNS/Archives des Jesuits de France via Public Domain)

Duffy's focus on key points of struggle in Teilhard's life helps to pare down the broad complexity of his mystical, scientific and theological writings.

In addition to his seminal writings, she examines his letters. In doing so, she reveals the human side of the great thinker and allows us to see that his ideas can be relevant to our own personal and intellectual struggles.

She describes a child deeply disturbed by his observance of mutability and decay, and who was motivated by the question, "What holds everything together?"

In his search for permanence and consistency, he became fascinated by both rocks and religion. He found his personal passion in the paleontological layers of Earth's crust, and his theological answer in Paul's letter to the Colossians (1:17b): "All things hold together in him."

Duffy says Teilhard combined his understanding of Paul with his reading of Henri Bergson's Creative Evolution to find a reconciliation of evolution and incarnation.

The author explains how Teilhard's work as a stretcher-bearer during World War I had a deep influence on his thinking and helped him understand the importance of community. She uses letters, his writings and historical events to tie together disparate experiences in his life, such as the hardships and successes of his paleontological work, his exile in China, his friendships and loves.

Advertisement

Running throughout the narrative is the tension of his struggle with church authorities, and his tenacious commitment to work within the church despite the censorship he endured.

Duffy skillfully brings the reader to the realization that these experiences and struggles were essential to his spiritual, theological and personal integration. She writes that he "refused to be satisfied with his faith until it fit with his experience." She notes that it took him about 30 years to build a faith statement that wove together "his human experience, available data about the cosmos, and the wisdom found in his faith tradition."

Teilhard's writings were stifled during his lifetime. Thus we see that the church, as so many times past, blocked the kind of creative thinking that could have helped it thrive in the face of intellectual flux. As Duffy writes, "He saw his role as helping to free the Church from outmoded and static ways of thinking and being."

He conceived of a divine spirit that was not above us, but ahead of us, pulling us forward toward convergence and salvation. It seems that Teilhard himself knew he needed to remain part of the Catholic faith to pull it forward toward his vision of integration.

Even though it was suppressed, the body of work Teilhard left is fascinating. We can only imagine the gifts that might have come from this great intellect if his struggle to theologically reconcile matter and spirit in the teachings of the church had been nurtured and brought to the light while he was at his creative best.

[Melissa Jones is an adjunct professor of liberal studies at Brandman University.]