A chromolithograph by Louis Dalrymple in Puck magazine, March 4, 1896, shows presidential hopefuls in a swamp containing "Jingoism," "Blunders" and "Demagogism." (U.S. Library of Congress/Keppler & Schwarzmann)

Can America return to some level of tortured but civil agreement, or will the rhetoric of fear, so deftly employed by President Donald Trump and his disciples, sustain such a level of partisan distrust that demonization rather than compromise becomes the standard, not only of politics but also of governing? Jon Meacham's The Soul of America: The Battle for Our Better Angels argues that Americans have suffered through demagoguery in the past and can do so again, but it will demand that they rediscover their soul.

Part history lesson, part polemic, Meacham's book expresses a hope that the American "soul" will survive the present threat that the Trump presidency poses. Drawing from Socrates, the Bible and St. Augustine, Meacham argues that the soul is that which "makes us us" in both our personal and national lives. In America, this soul is animated by a "creed" that demands liberty and equality for all. Yet this creed can be upheld only if we side with the "better angels" of our nature instead of retreating into fear. Those better angels reveal their inspiration when we welcome neighbors and strangers rather than exclude them.

For Meacham, the state of the American soul can be determined by the behavior of its presidents. In a style well-suited to a general reader, Meacham narrates a history of the American presidency since Abraham Lincoln. He highlights "consequential" presidents: those who are future-oriented, draw from peoples' best instincts and provide moral leadership, which Trump "rarely does." Such dignified presidents unified the country and instilled hope.

No president is perfect, and Meacham doesn't shy away from criticizing the moral ambiguity or outright racism of past presidents that he admires. Regardless of their bigotries and brief lapses into fear and error, our greatest presidents saw their role as serving all Americans — not merely their electoral base or congressional sycophants — and moving the country forward morally.

In Meacham's pantheon of progressive presidents, one expects to find Franklin Roosevelt. Meacham acknowledges the moral failure of his internment of Japanese-Americans, but praises the faithfulness, hopefulness and sense of moderation that Roosevelt followed to get America out of the Depression. Indeed, Meacham sees the establishment of the middle class in the mid-20th century as "one of the greatest achievements of history," one that couldn't have happened without the New Deal's concerted government intervention. Meacham identifies FDR's progressive orientation, his openness to interconnection with, rather than isolation from, the world, as an "essential presidential function."

Advertisement

Other progressive presidents may surprise some readers. Ulysses S. Grant faced the arduous task of saving the Union following Andrew Johnson's disastrous presidency. Johnson catered to his base — white Southerners — gave into fear and failed to move black enfranchisement forward; instead, Johnson tried to reverse the progressive steps taken by Lincoln by creating crises and feeding conspiracy theories.

In contrast, Grant "appreciated the bigness of his office and the times," applying "unionist principles" despite obstreperous Southern politicians still smarting from the defeat of the Civil War and the abolition of slavery. Grant oversaw the passage of the 15th Amendment that extended voting rights to African-American males and cracked down on the Ku Klux Klan, repelling the "reign of terror" raging in the South.

Another surprising object of praise is seldom-lionized Calvin Coolidge, who, at least in private correspondence and speeches, strongly supported the political rights of black citizens.

For Meacham, though, the model of progressive American leadership is Lyndon B. Johnson, who understood that noble tasks of the presidency are creating compromise and achieving social justice. Johnson realized that the presidency gave him special powers, but he used them on behalf of those who were disempowered, spurred as he was by a significant and persistent protest movement. Johnson invested the political capital amassed from being a Southerner and a "master of the Senate" who had a rapport with Southern strategists like Richard Russell, into the cause civil rights for African-Americans, far exceeding the accomplishments of John F. Kennedy, who feared losing the white vote if he proceeded too radically.

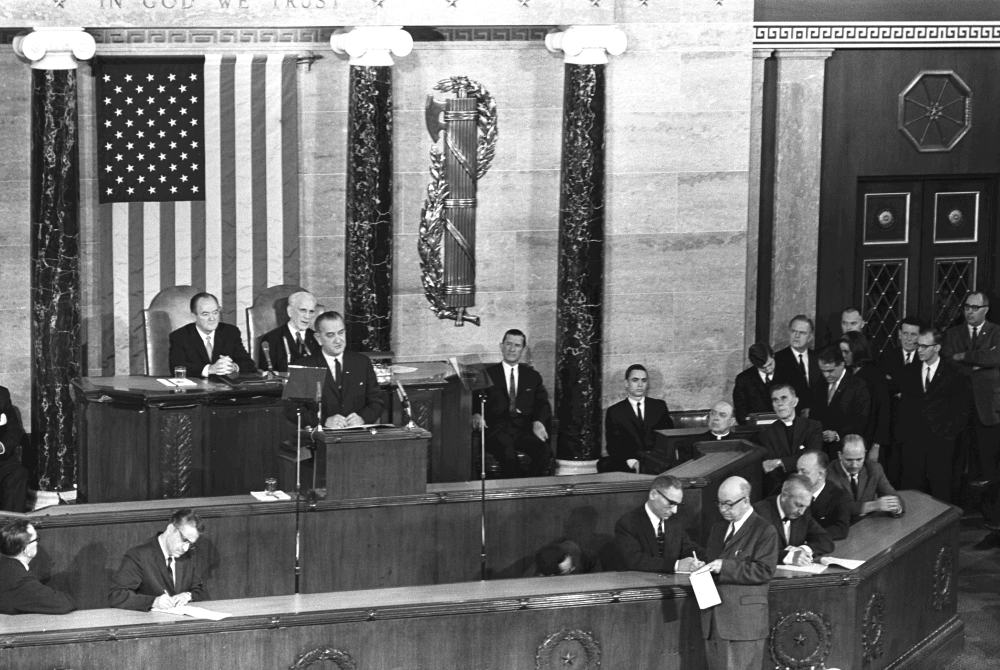

Johnson had a proper and productive view of presidency: It gave one person the power to unify the country behind just causes, which was especially true of civil rights — a tough issue that demanded the leadership that only a progressive president who refused to compromise could bring about. Meacham showcases Johnson's "We Shall Overcome" speech before Congress, providing the full transcript.

President Lyndon Johnson delivers his "We Shall Overcome" address to Congress, urging passage of voting rights legislation, at the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C., on March 15, 1965. (LBJ Library/Cecil Stoughton)

Contrasted with Meacham's progressive heroes, Trump is sadly regressive and retrograde. Throughout The Soul of America, Meacham profiles a series of Trump analogues, most of whom have become pariahs of American history. Trump is the glad inheritor of the "white populist tradition" of Strom Thurmond, George Wallace and David Duke: a tradition that gains political traction by evoking a fear of the unknown. More indirectly, Trump's exploitation of fear connects him to the KKK. Trump's "build the wall" cheerleading echoes a racist Georgia governor whom Meacham quotes proposing the same solution at a Klan rally.

Like Trump, Sen. Joseph McCarthy capitalized on the conspiracy promulgated by shady sources like the John Birch Society. McCarthy was a "freelance performer" who had no clear political philosophy. In Trumpian fashion, McCarthy used the media to irresponsibly sensationalize bogus claims. The senator's ability to garner headlines created a mutual dependency with the press, who sought any crumb to sell papers. Nevertheless, this dependency did not keep McCarthy from bashing the press when it was politically advantageous to do so.

Refreshingly, Meacham finds a fictional mirror for Trump in Shagpoke Whipple, a demagogue from Nathanael West's A Cool Million who runs for president on the platform of bringing America back to greatness through the elimination of immigrants and prioritizing American interests over international cooperation.

The fear that Trump spreads is contagious and destructive, but Meacham holds out hope that Americans can survive and transcend this presidency: "We shall overcome" is his stated theme. But getting beyond Trump will demand public resistance, congressional action and a free news media that can act as a thorn in the side of those who would misinform. Against isolationism and jingoism, Meacham proposes a "clear-eyed" American exceptionalism that boasts constitutionally established corrective function and a tradition of overcoming hatefulness and injustice; for Meacham, true patriotism recognizes our flaws but maintains a belief in our national soul.

Nevertheless, there is a sad irony even in such a genuinely optimistic treatise. Meacham hopes that we can rise above the partisan rhetoric, but his argument, and especially his extended critique of Trump and Trumpism, may be read as just another contemporary jeremiad that appeals only to Trump haters and repulses those for whom the support of Trump has risen to a level of belief that withstands rational scrutiny. Hence, a significant percentage of Americans may accuse The Soul of America of contributing to, rather than remedying, disunity and dissension. Despite his best intentions, Meacham's unabashed hope may be distrusted as thinly veiled antagonism in a nation that may have already lost its soul.

[Dennis D. McDaniel is associate professor and chair of the English department at St. Vincent College.]