(Pixabay/Phyllis Rawley)

Some of today's best feminist theologians are writing fiction. I do not refer to their erudite, critical analyses of texts and concepts as novels. Rather, I alert readers to their new excursus into literature. I wondered aloud why they have embraced this genre. So, I asked them.

Theologians Mary Judith Ress, Ivone Gebara and Susan Brooks Thistlethwaite are producing compelling fiction both related and unrelated to their primary theological work. Join me for a quick tour, and order your copies now for what I think are solid, page-turning (or screen-swiping) reads with important insights sans footnotes.

Ress is an American who has lived since the 1970s in El Salvador, Peru and Chile, mostly as a Maryknoll associate. She was a co-founder of the eco-feminist theology/spirituality Con-spirando Collective, which published a widely read journal.

Her theological work, especially Ecofeminism in Latin America, established her unique voice — still a gringa of sorts, living in Santiago, Chile, but a global feminist actively engaged in Latin American struggles for life.

But why fiction now? When the four religious women were murdered in El Salvador in 1980, Ress said, "I was traumatized — Dorothy Kazel replaced me on the Cleveland Mission Team. I could as easily have been driving the van with Jean to pick up Ita and Maura. … I also knew Ita here in Chile before she went to El Salvador."

Haunted by her deep connections to women like herself, she decided to write the inside stories of these women. Fiction was the perfect vehicle to convey their faith, loves, losses, failings and enduring commitments. As she told me recently, "I admit to being on a crusade to raise up these amazing nuns who work in the trenches. … They are the real heroines of the Catholic Church."

So emerged Sister Meg and company in Ress' debut novel Blood Flowers, which grips like a glove as the stories of dirty politics, murders and natural disasters tumble out.

Sister Mary Clare, who runs a U.S. women's shelter, comes to life in Ress' second, complex work of fiction, Different Gods. An odd man suffering from aphasia arrives on the scene proclaiming himself St. Francis. Her efforts to help him find his footing involve Franciscan men, Mary Clare's gay cousin who is a nurse, and multiple members of her community, none of whom understood all the layers of the visitor's life. Together, they manage to sort him out and glean from his wisdom.

There are competing worldviews at play, Ress explains, "struggles with being faithful to progressive but still traditional Christian beliefs, versus the allurement of long-forgotten shamanic wisdom as practiced by the indigenous people of the Amazon rainforest." Thick narrative rather than complicated explanation lays these out in relief.

I will not spoil the read except to say that two people I know stayed up way past their bedtimes to find out what happened and why. I cannot recall the last time I did that for a theological book.

Brazilian feminist theologian Gebara just published her first work of fiction, Travessias e Acenos (Portuguese for Crossing and Saying Goodbye and not yet available in English). As elegantly written as her theology, this novel honors the memory of her Syrian women ancestors who made their way to Brazil. They started new lives, learned a new language, used brooms and sewing machines to keep house and make a living, and still cooked the foods of their native land. This is the story of so many immigrant women worldwide.

As with Ress, fiction for Gebara is a better vehicle than theology or even history because it admits the full range of human experience. As Gebara told me recently, her writing is a way of "showing how humanity is an immense mix of lives, traditions, fears and small joys."

She says, "Our origins are common and different. There is a beauty in all of this that can only be captured in poetry or a novel."

Her childhood memories of these women ground the characters. By sketching them, literally, "I had no intention of doing theology. … What I wanted to do was live with them in the intimacy of my memory, listen to them in me and come to know myself better in them. To write novels is a way to encounter real people in one's own history and not only ideas."

I could smell the Syrian spices as I struggled with the Portuguese. A smart publisher will have a beautiful English translation out soon. I was enthralled by the text and captivated by the line drawings of the women and their struggles. Gebara continues to write theology, thank heavens, but I hope this gem portends more fiction to come.

Theology professor, minister and former president of Chicago Theological Seminary, Thistlethwaite has added murder mysteries to her theological corpus of 14 authored or edited books. Far more than a clever way to get students to ponder ethical questions, these books are the real thing in their own genre.

Her heroine, Kristin Ginelli, is a former police officer turned philosophy professor who spends her considerable privilege stopping injustice. Risking her life, she solves the mystery of Where Drowned Things Live. In the process, she excavates the sexual violence, racial/ethnic oppression, Christian fundamentalism and blatant sexism that underlie the murder of her Korean woman student.

Without a didactic sentence between its covers, this book could be the central text for a graduate ethics seminar. Students would be glued as I was to a surprising story with a lingering, multifaceted message.

The further adventures of Kristin unfold in Every Wickedness. Another woman is dead from what may not have been accidental causes. Kristin is on it. Thistlethwaite adds discussion questions to this volume that point to her lifelong work to end violence — the sex industry, the opioid crisis, poverty and homelessness, the ageless struggles between good and evil.

Thistlethwaite explained her method to me: "I chose to write mystery fiction as it is, to me, an ethically satisfying genre. … One can create a moral universe. … While terrible things happen, those acts are dragged into the light and the perpetrators are stopped. This allows the reader the psychological space to consider how violence happens, and why it is so often hidden."

She has a third volume on the fire that I plan to pre-order.

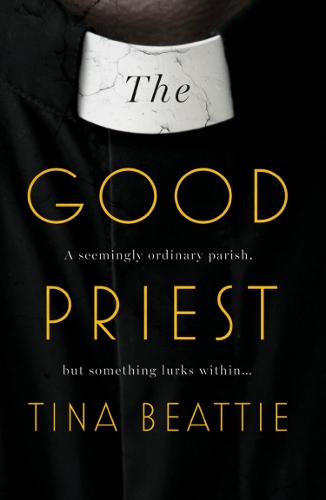

The welcome addition of fiction writing to feminist work in religion is the fruit of these scholar/activists' careful thinking, clear writing and deep commitments to the world's well-being beginning with women. It is sure to inspire more such creativity. For example, British theologian Tina Beattie has fictionalized the complexities of abuse in her novel The Good Priest. It is on my list. And who knows what is on my own writing agenda.

[Mary E. Hunt is a feminist theologian who is co-founder and co-director of the Women's Alliance for Theology, Ethics and Ritual (WATER) in Silver Spring, Maryland.]

Advertisement