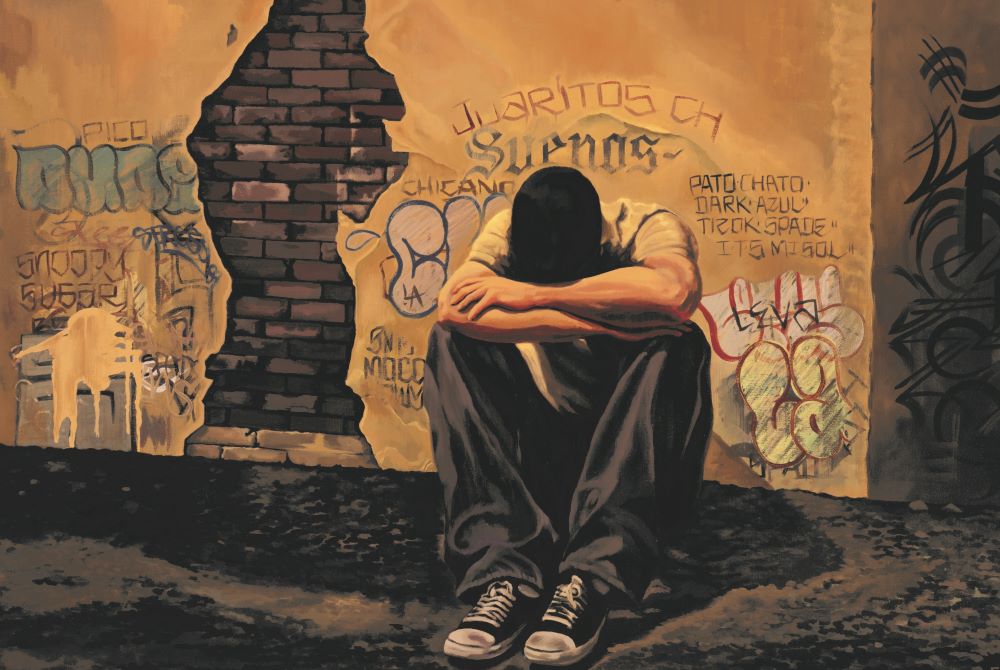

"HIS-STORY" depicts a "homey" contemplating life in this acrylic on canvas by Fabian Debora. (Courtesy of Loyola Press)

At first, I can't tell what he's doing. I have just stepped into the office of Jesuit Fr. Gregory Boyle, the founder of Homeboy Industries, the largest gang intervention, rehabilitation and reentry program in the world. The lobby behind me is buzzing with activity, dozens of people passing through on their way to Homeboy's many support classes, to see lawyers or therapists, to have tattoos removed, or to work in one of the social enterprises onsite. Many more are walk-ins, waiting in the lobby's crowded rows of chairs to see G, as he is affectionately known.

Greg's desk faces the glass wall of his office, and his eyes are on the lobby as he talks to me with Fabian Debora, one of the homies and the director of Homeboy Art Academy. Greg is shuffling some papers under his desk. He pulls out a pen. Then he starts to call names. It is only then that I realize what's happening: Father G has taken out his wallet and is putting money in envelopes to give to specific people who have asked for help. He calls his runners to deliver them, one by one. I have been here less than five minutes, and I have already been reminded of the love of God.

I'm here to talk with Greg and Fabian about their new book, Forgive Everyone Everything, in which many of the stories of Homeboy are told, both in word and in image through Fabian's art. Those who have read Greg's previous books (Tattoos on the Heart, Barking to the Choir and The Whole Language), will find themselves at home here. As much as these are stories, they are also parables, windows through which we can peer to see God, and to see the sacredness of each other.

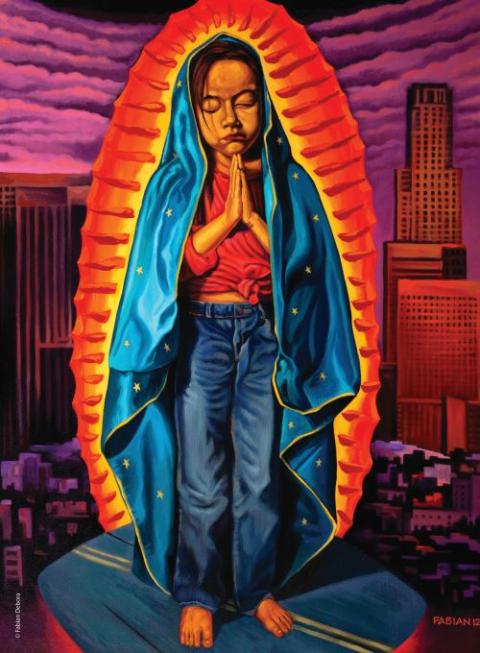

Artist Fabian Debora was inspired by his daughter Maya to paint "The Virgin of the Mary," titled by Maya, as homage to the many street murals of the Virgin in Los Angeles. Debora hoped to convey to his daughter and all women that they should see themselves as powerful and radiant as the Virgin Mary. (Courtesy of Loyola Press)

Greg's stories are often told in the present tense, and that is because he is so present in all of them, so deeply attentive to the person before him. One cannot help but think of the name that Hagar gave God in the book of Genesis: El Roi, the God who sees. Greg's writing honors the pain and the beauty of every person he encounters, and invites us to do the same, drawing us all into what he calls exquisite mutuality — kinship. Homeboy is not a place that simply provides services. It is a place where people are introduced to their own goodness and held up by a community of unconditional love.

The book hinges on this central theme: "We are sacramental to our core when we think that everything is holy. The holy not just found in the supernatural but in the Incarnational here and now. The truth is that sacraments are happening all the time if we have the eyes to see."

If the seven sacraments recognized by the Catholic Church are the short list, I ask Greg and Fabian what's on their long list of sacraments. Greg looks out into the lobby and spots a homie named Trujano. He pulls out his phone to show me a text he recently received from him — it's a portrait of Trujano, painted by another homie, under which he's typed, "Starting bid, $1500." Greg's reply: "$2000." This is as apt a summation of Greg's mission and Homeboy's as any: ushering people into a place where they can see their own limitless worth. "There's a sacrament," he says.

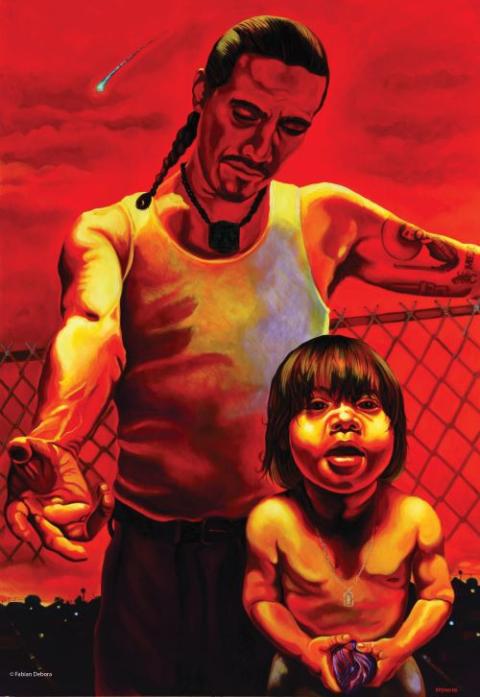

"Fallen Stars" is a self-portrait by Fabian Debora and his daughter, intended to evoke reflection on the strength, tenderness and forgiveness of God as Father. (Courtesy of Loyola Press)

"If we're open and willing to see God in every person, as we are called to do, then not a day goes by without a sacrament," Fabian continues, "It happens all the time."

Fabian, too, has a truly sacramental vision; what Greg does in words, Fabian does in paint. His work draws richly from the strands of his life and community, incorporating Indigenous, Chicano, Catholic and Angeleno elements. Boyle Heights features prominently, as does Our Lady of Guadalupe. Fabian views his work and his creative process as a ritual and a prayer, and it is hard to miss that in the images that fill the book. The faces that gaze at us from his portraits welcome us into a holy space of contemplation, of reflection on what binds us together as humans, and what binds us to the heart of God.

"It's always taking the beauty within my community and removing the stereotypes of identity, culture, religion and gender," Fabian says. "That is my mission as an artist." Fabian offers one of the paintings in the book, "Convicted All-Stars," as an example. In the foreground a pair of the iconic Converse sneakers hangs from a telephone wire against the backdrop of a midnight blue sky. People outside his community often point out sites like this one as places for their children to avoid; where shoes are hanging on a wire, they say, it’s a dangerous place, where drugs are dealt or people are killed. "It's the definition of an outsider looking in," Fabian says, because in his childhood experience, tossing up old shoes was a simple game of horseshoes, played for the fun of seeing who could throw them higher. "I see God in those shoes," Fabian says, "and the skies are open to receive that image."

Fabian wants the homeboy, the gang member, to see that they, too, are the body of Christ. In one of his paintings, the Virgin's floral dress flows down onto the tattooed back of a homie. In another, she appears to Juan Diego in the form of a homeboy; Tepeyac has become the projects. This, too, Fabian wants us to see, is a holy place, a place of encounter with the divine.

Advertisement

As joyful a place as Homeboy is, there are, of course, tragedies and sorrows that mark its days. Greg reminds me, "We haven't all arrived anywhere, but people are constantly being invited to wholeness, which is holiness, I suppose, but there's nothing once and for all about it. People are all just walking each other home. It's all about relational wholeness, and it's the relationship that heals."

I have occasion to reflect on this again the next day when talking to Todd, a man as tender as he is tall, who has taken me under his wing during my visit. He invites me outside to meet Carmen, who brings lunch and drinks for the homies every day for only $2. Todd asks if he can buy me lunch, but I demur, saying that I want to make sure everyone else has a chance to eat first. "Don't worry," he immediately replies with a smile, "We never run out."

This is the God you will encounter in Forgive Everyone Everything: One who never runs out of love, never runs out of mercy, never runs out of delight in every human being. One who inspires us all to do the same.