Seymour Hersh (Don J. Usner)

I cannot read Seymour Hersh without stirring up memories from my years as a journalism teacher. Journalism embodies the basic virtues of society. We need the press to condemn what is wrong and embrace what is best for the community.

Foreign correspondent Richard Harding Davis' description of the German army marching into Louvain in 1914 was a turning point in history. Where would we be without Robert Fisk's dispatches from the Middle East? CBS Eric Sevareid's final TV analysis on his trip to Vietnam — "There comes a time when the heart must tell the head what it must do" — inspired me to write his biography. When Hersh arrived at The New York Times, columnist Anthony Lewis befriended him.

Seymour Hersh (Don J. Usner)

Now, at 81, Hersh sees himself as a "survivor from the golden age of journalism" as we slide into a culture where cable TV panels of "experts" answer every question with the "two deadliest words in the media world" — 'I think,' " and when so many newspapers are dying or firing half their staff in order to survive. How well can journalism fulfill its inherited obligation with integrity and courage?

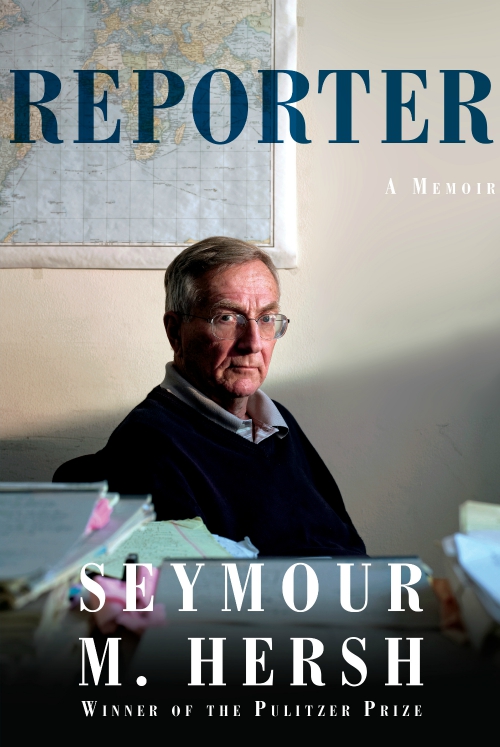

This book, Reporter: A Memoir, is an apologia, a report on his role in the big stories that exposed the corruption of the federal government and foreign policy; it even scolds the press itself. Hersh plays the Lone Ranger, who may or may not have the cavalry to back him up.

This is also a textbook that every journalism professor should assign to his or her class. He draws rules from his University of Chicago courses and from his first job with City News. The first rule: When two police officers were shot, and a lot of blood made them look dead, he learned not to report the "deaths" until the deaths were verified. Second, ingratiate yourself with the desk sergeant; you will need his support when news of a mass murder comes in late at night.

The third is: Don't censor yourself. When news of a multiple murder came in, Hersh arrived at the scene of a shoot-out just in time to hear one cop tell another that he had "told the [N-word] to beat it and then plugged him." Hersh could prove the man had been shot in the back. He had a "story," but no one was interested. Reporters are tempted to "go along" and look the other way. He concludes, "I had found my calling and I learned, very quickly, that it wasn't perfect. Neither was I."

By 1964, Hersh was married and working with the Associated Press in Chicago, reading a lot of Bernard Fall's work on Vietnam and I.F. Stone's debunking the Johnson administration on Vietnam by outworking every journalist in Washington. When Hersh had difficulty placing some of his findings, like the U.S. bombing of civilian targets, Robert Hoyt, editor of the National Catholic Reporter, reached out and offered to publish anything he wrote. Later, Hoyt offered to syndicate a column every month. For one year, Hersh put aside his journalism to serve in Eugene McCarthy's presidential campaign, which left him disillusioned by McCarthy's irresponsible neglect.

This book is also an exercise in the education of Hersh's conscience; he tells us that at 32 he had been in journalism for 10 years and learned that "the U.S. military would choose to lie and cover up rather than face an unpleasant truth," and that mainstream journalism was also adept at looking the other way.

Advertisement

He had come to these realizations just as he learned about a GI at Fort Benning, Georgia, who was being court-martialed for killing 75 civilians in South Vietnam. The search for the whole story became the mountaintop of Hersh's career. First he had to track down 1st Lt. William Calley Jr., whom he found by walking into the fort where Calley was somewhere housed, and late at night plodding through every dorm, knocking at every door for days.

One night, worn out, he headed for the gate, until a GI called him back, "Rusty is here." Hersh and Calley shook hands, and they sat down for a couple of beers. Hersh was there to "get his side of the story" and found not a monster but "a rattled, frightened young man, short, slight, and so pale that the bluish veins on his neck and shoulders were visible." They talked long into the night, and Hersh went on to dig deep enough for four major articles that won the Pulitzer Prize.

In 1972, Hersh joined the staff of The New York Times, working in both the New York and Washington bureaus, focusing on everything wrong with the Vietnam War. After six months, he was proud of his association with the Times, but he wished he could write more about "the secret world of Washington." Any time a story got hot, he had to "run it by Kissinger." When Hersh wrote a story critical of Kissinger, the Times' "Scotty" Reston anxiously threatened, "If you do this Henry will resign." Kissinger often threatened to quit, but never did.

Hersh respected executive editor Abe Rosenthal, who appreciated Hersh's respect for the Times but insisted that everyone love it the way he did. Hersh became more disappointed with the failure of the editors to look hard at corporate America. After several months he learned that the business editor had sent a confidential note to Hersh's editor warning about his bias against America corporations. The business editor was appalled. Hersh resigned immediately and never worked regularly for a newspaper again.

Back at The New Yorker, a major accomplishment was his article exposing the American responsibility for torture at Abu Ghraib. He wrote up a new angle on the American assassination of Osama bin Laden, too, but The New Yorker decided against publishing it. Several times, Hersh met with Syrian president Bashar Assad, without mentioning that Assad had killed 100,000 of his own people since 2011.

Hersh speaks frankly about his own personal shortcomings — rough temper, late-night drinking capacity and compulsive spurts of violence, as when he threw his typewriter out the window without first opening it.

But he ends on a gentle note. He visits New York Cardinal John O'Connor to talk about his predecessor Cardinal Francis Spellman's relationship with President John Kennedy. O'Connor tells him how, when he became archbishop, he found a package locked in a desk drawer, marked by Spellman, "Not to be opened by anybody." O'Connor opened it and found a pile of letters, decided that they should never be seen, and mailed them to Vatican City.

As they walked to the door, says Hersh, O'Connor "threw his arm around me," and said, "My son, God has put you on earth for a reason, and that is to do the kind of work you do, no matter how much it upsets others. It is your calling."

[Jesuit Fr. Raymond A. Schroth is emeritus editor of America and comes from a journalism family.]