(Unsplash/Priscilla Du Preez)

2021 is a nebulous time to be releasing a book. We are still in the worst of the pandemic, but there are faint signs that change is coming on the horizon. We are spending more time online than ever before, but we are also wearier of being online than ever before, with "Zoom fatigue" and internet burnout entering the national conversation.

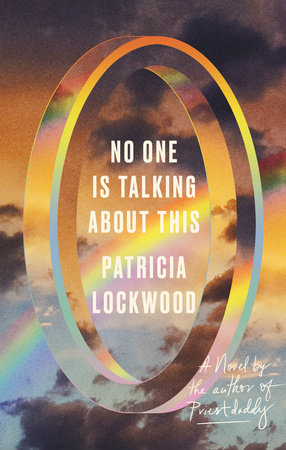

Many works released this year and last, thanks to the publishing cycle, were written pre-COVID-19, and on occasion, the differences between a book depicting life in the before times and life today are so glaring as to make the book painful to read. This is sometimes the case in Patricia Lockwood's first novel, No One Is Talking About This, particularly in moments when the protagonist is traveling around the world and experiencing the surreality of jet lag and new cultures glimpsed only in moments before moving on to the next destination.

The novel feels like 2019, recalling the kinds of conferences, TED Talks and internet influencer culture that required living life in the liminal spaces of airports and hotel conference rooms and the crammed, dim backrooms of bars. These physical moments are the setting for the first half of Lockwood's novel. Her unnamed protagonist is a woman of indeterminate but millennial-leaning age who became a celebrity for making a joke on Twitter that went viral. Now she spends her time absorbed in "the portal," the phone or laptop or tablet screen that contains "what she thought so longingly of as my information … my everything I ever needed to know."

When she's not online, she's traveling the world explaining what it means to be online, the endless streams of jokes, memes, viral videos and everything else the outrage machine generates in a 24-hour cycle, ready to suck us in and prod us into replies. "Why had she entered the portal?" she asks herself at the end of the book. "Because she wanted to be a creature of pure call and response." Donald Trump is very much present in the book, not just as an overarching presence chewing up our collective attention spans with his monstrous ego, but as "the dictator" who occasionally appears in the nonlinear narrative of the portal, a long shadow hovering over a roiling sea.

The portal Lockwood's protagonist is addicted to feels a lot like Twitter, where "every day their attention must turn, like the shine on a school of fish, all at once, toward a new person to hate. Sometimes the subject was a war criminal, but other times it was someone who made a heinous substitution in guacamole." And that quote might give it away, but what saves the first half of the novel from collapsing upon itself in an endless stream of bits and bobs and internet detritus, products of the Very Online mindset, is the fact that Lockwood is funny. Hilarious, even.

Her previous book, Priestdaddy, was a memoir about growing up with a father who converted to Catholicism and became a priest, and it was a very, very funny book. Lockwood's own Twitter account is very, very funny. I marked maybe a hundred different funny lines in my copy of the book, but like Twitter memes when you try to explain them to someone who isn't on Twitter, these lines are funny because of the context they're in within the scroll of information.

Advertisement

About that structure: midway or so through the book, the protagonist gets a text from her mother saying "something has gone wrong" and "how soon can you get here." At that point, the tone of the book takes a radical shift. Without giving too much away, the second half of the book focuses much more specifically on family, women, reproduction and health care. This part of the novel is where the Catholic Church emerges, like Trump, a shadow hanging over the book. Again, without giving too much away, Lockwood's narrator and her family have many justified problems with how the church treats women. Catholicism is not a significant theme in the book's second half but one that runs through it, reminding us that in the "real world" versus the portal, our choices and how we make them have implications that last longer than the life cycle of a viral tweet.

It's a jarring and daring choice on Lockwood's part to structure the book this way, and the second half wrestles with what it means to live outside of the internet in ways that can feel poignant and painful when we are still trapped online due to COVID-19. The protagonist feels the urge to tell a child "how it felt to go to a grocery store on vacation; to wake at three a.m. and run your whole life through your fingertips; first library card; new lipstick; a toe going numb for two months because you wore borrowed shoes to a friend's wedding." Those experiences feel more and more precious and rare as pandemic time marches along.

Some readers will struggle with this shift and with the lack of narrative structure in the book's first half. But if you're willing to immerse yourself in the scroll of Lockwood's narrative, there is plenty of humor and empathy to be found. Because of the book's plot, and because of how we live now, there is also plenty of melancholy and sadness, but that's what makes for a human life, offline or on.

[Kaya Oakes teaches writing at UC Berkeley. Her fifth book, The Defiant Middle, will be released in November, 2021.]