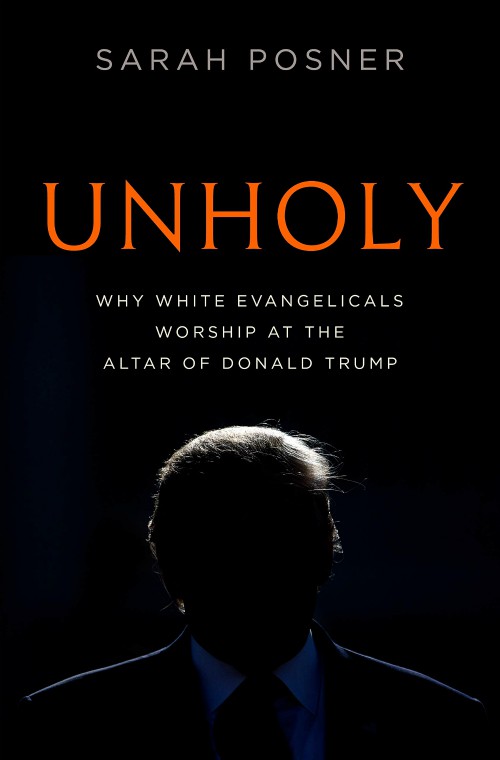

President Donald Trump holds a Bible as he stands in front of St. John's Episcopal Church in Washington June 1. (CNS/Reuters/Tom Brenner)

Sarah Posner's timely, meticulously researched Unholy intertwines two stories. As its subtitle asks, how can white evangelicals, longtime strong advocates of character in political leaders, worship so fervently at the altar of President Donald Trump? The answer to that question requires historical examination of the religious right movement, which has now amalgamated with the "alt-right," Posner proposes, to form the base of the Republican Party.

Posner has tracked the religious right carefully for years. Few commentators are better equipped to tell this story.

As the "unholy" tag indicates, the other story Posner tells suggests that the religious right's alliance with Trump has proven to be less than holy. Citing abundant evidence, Posner concludes that "religious right leaders have given moral cover to the president's racism and white nationalism" and "have helped make the unthinkable — an overtly racist American president — a reality."

In her exhaustive research for this book, one of many scholars she interviewed was Billy Graham biographer Randall Balmer, who told her that with its effusive buy-in to the Trump presidency, the religious right has come "full circle to embrace its roots in racism" and has "finally dispensed with the fiction that it was concerned about abortion or 'family values.' "

The well-documented history of the religious right is a key contribution of this book. But that history unfortunately poses (or should pose) problems for Catholics who have chosen for some years now to vote in alliance with white evangelicals, claiming a pro-life motivation.

Catholic readers of Unholy might be tempted to conclude that the history of the religious right Posner sketches in no way implicates them. Her focus is, after all, to ask why white evangelicals worship at Trump's altar. Posner notes that "the well-worn foundation story of the modern religious right" has the movement originating in evangelical and Catholic opposition to Roe v. Wade.

Advertisement

But Paul Weyrich, a founding figure of the religious right who was Catholic (he transferred from the Roman to the Melkite rite after Vatican II), consistently asserted that the religious right coalition originated in racial backlash. It was reacting specifically to the insistence of the federal government following civil rights legislation of the 1960s that church-based schools receiving federal funding must adhere to non-discrimination guidelines.

Posner writes:

As much as the Christian right of the twenty-first century is now fixated on abortion and sexual politics, the backlash against the efforts of the federal government to desegregate tax-exempt private schools is embedded in the movement's DNA. The white evangelical attraction to Trump was not in spite of his extended birther crusade against Barack Obama, his racist outbursts in tweets and rallies, and his administration's plans to eviscerate federal protection of racial minorities from discrimination in housing and education by eliminating their ability to show discrimination based on the disparate impact of a policy, as opposed to having to prove discriminatory intent. The Christian right movement was born out of grievance against civil rights gains for blacks, and a backlash against the government's efforts to ensure those gains could endure.

If this historical analysis is correct — and Posner and many others, including Balmer, offer sound documentation for it — then the self-exculpatory story many Catholic voters like to tell, maintaining that they are "only" voting pro-life and not colluding in racism when they vote in tandem with white evangelicals, may need to be reconsidered.

On this point, it's instructive to read Posner's book together with Robert P. Jones's new book White Too Long, which came out not long after Unholy was published. The two form instructive companion pieces offering timely commentary on the religious underpinnings of many of Trump's most loyal supporters in advance of the 2020 presidential election.

Those underpinnings deserve close analysis when, as Posner reminds us, Catholic right-wing activist Steve Bannon declared, following the 2016 election, that "evangelical and conservative Catholic turnout" was " 'the key that picked the lock in North Carolina, Florida, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Iowa, Michigan, and Wisconsin,' making the difference for Trump's win."

Jones' White Too Long insists that, official church statements condemning racism notwithstanding, it's the actual record of lived Christianity in the U.S. to which we need to pay attention if we want to understand how white churches have historically dealt with white supremacist racism. He writes:

The historical record of lived Christianity in America reveals that Christian theology and institutions have been the central cultural tent pole holding up the very idea of white supremacy. And the genetic imprint of this legacy remains present and measurable in contemporary white Christianity, not only among evangelicals in the South but also among mainline Protestants in the Midwest and Catholics in the Northeast.

Put Jones' analysis side by side with Posner's, and one cannot avoid asking about the role that white supremacist ideology might have played in the political choices that led six in 10 white Catholic voters to join eight in 10 white evangelicals in placing Trump in the White House in 2016. This analysis invites open critical discussion among American Catholics about what many observers find to be persistent, deeply entrenched racism in their church.

It would be a pity, a self-defeating blow, if any group within the U.S. Catholic Church sought to censor or suppress such open discussion of this critically important issue at a pivotal moment in American political and religious history. Or so it appears to this particular Catholic who happens to have been raised Southern Baptist and who entered the Catholic Church when his family's church split over the question of accepting Black members in 1965.

Given these formative experiences, I am surprised that Posner tells us at the outset of her book that she was surprised that Trump quickly elicited such zealous devotion among white evangelicals after announcing his candidacy. Count me among the unsurprised, regarding both white evangelical and white Catholic fervor for the current occupant of the White House.

[William D. Lindsey holds a doctorate in theology from St. Michael's College, Toronto School of Theology, and is a retired university theology professor and administrator.]