The steeple of the Church of the Assumption is seen in the background as neighbors clean up debris left in a tornado's wake in Nashville, Tennessee, March 3, 2020. (CNS/Tennessee Register/Rick Musacchio)

This year reminded us that we are vulnerable creatures able to be felled by multiple causes, from the tiniest virus to the greatest natural forces of earth, water, fire and wind. Modern science often allows us to push this unpleasant knowledge to the back of our minds, but the widespread suffering of 2020 made it clear that chaos caused by random, unseen forces can still befall us.

In his book, Tornado God: American Religion and Violent Weather, Peter J. Thuesen examines the phenomenon of tornadoes and other wind events. He asserts these specific weather experiences are uniquely tied to human ideas about God. Thuesen notes that religions from time immemorial have described destructive wind events as demonstrations of power from a supernatural entity.

He writes, "Tornadoes, and weather generally, put us in touch with the origin of religions, which arose in part as humans struggled to account for the forces of nature." The author notes that intellectuals such as Sigmund Freud and Karl Marx believed this connection between weather and an awesome divinity was a childish personification of the forces of nature that humanity would outgrow. Thuesen argues that modern rationalists "underestimated the staying power of the Storm God." His book examines an extensive array of deadly North American tornadoes and their aftermath to demonstrate that the "Storm God" still elicits awe and dread.

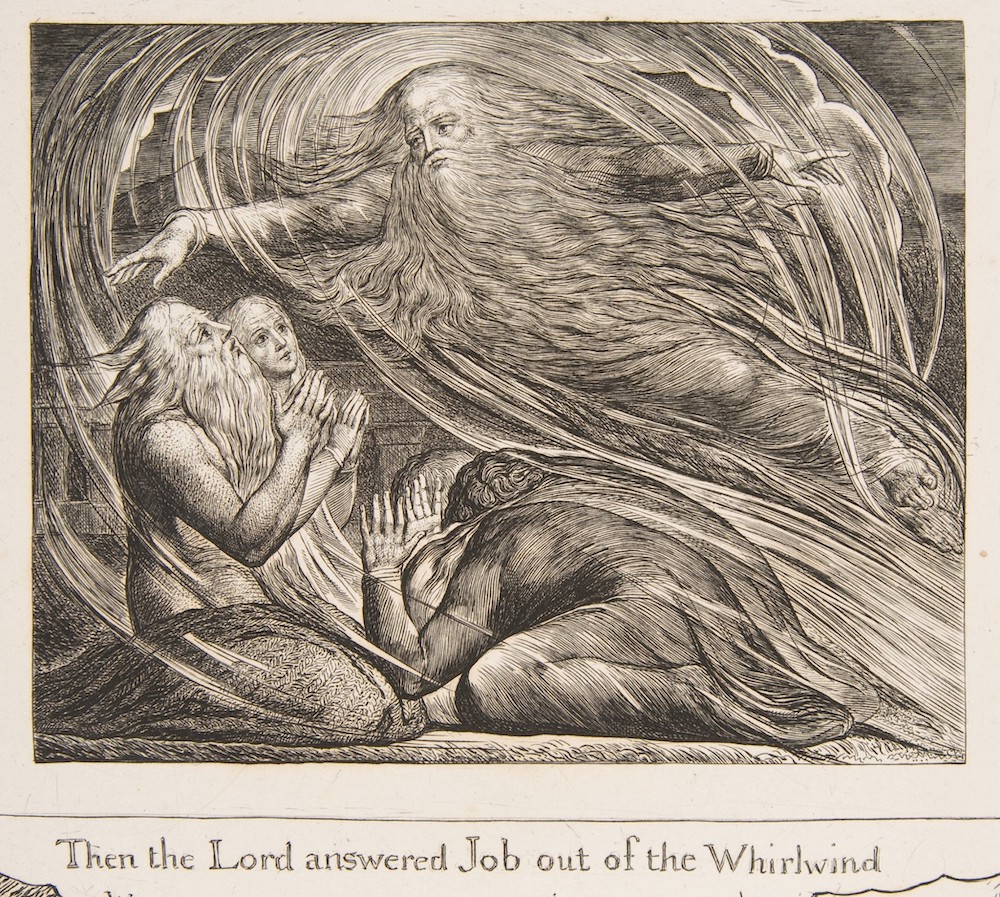

The author explains that, like God, weather is unknowable and manifests uncontrolled power, so it is not surprising to see the two tied together in the human psyche. He points to many instances of terrifying winds in both the Hebrew Bible and New Testament. Probably the best-known of these is from the Book of Job. Not only are Job's children killed by "a great wind from the wilderness," but after Job laments his torments, "the Lord answered Job out of the whirlwind."

Detail of engraving "The Lord Answering Job out of the Whirlwind" by William Blake, 1825-26 (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Tornadoes arise in the United States more than any other geographical region, and they are particularly common in the Bible Belt. Based on this, the book unfolds as an intellectual history that examines news articles, editorials and mostly Protestant sermons and theological treatises that arose in the wake of deadly tornados.

Looking for the hand of God in tornadic winds is not a purely Protestant activity, though, and Thuesen says Catholics have also "scrutinized natural phenomena for moral messages." Some see the destructive winds as punishment for personal or societal offense against God, but the faithful also see divine intervention, perhaps a reward for faith, in stories of close escapes from death and destruction.

The author relates a story about the Jesuit mission at Sault-St-Louis, Quebec. Around midnight in August 1683, "all the monsters of hell" arrived in the form of a whirlwind that destroyed the chapel. Miraculously, three Jesuits who were in the chapel survived without serious injury. Later, they shared that each of them had prayed earlier that day at the nearby tomb of the revered Kateri Tekakwitha, a Native American convert to Catholicism. This was one of two meteorological miracles attributed to her influence. She was eventually elevated to sainthood by Pope Benedict XVI in 2012.

Thuesen also describes how Christopher Columbus, when caught in a terrible storm on one of his trips to the New World, sent up a promise to do a pilgrimage to the Castilian Shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Extremadura. The ships were saved, but Columbus noted in his diary that he feared the storm was due to his "small faith and loss of confidence in Divine Providence." Upon his return to Spain, Columbus fulfilled his vow.

Advertisement

The author's meticulous research demonstrates that gratitude for divine providence is common among those who are spared from the path of a tornado's destruction and those who survive a direct hit. This sets up an age-old theological problem: If God can control who is spared from catastrophes, why are some seemingly good and innocent people allowed to die horrible deaths? The question becomes especially thorny when innocent children are killed.

This problem of theodicy, the paradox of why an omnipotent, all-loving, all knowing God allows suffering, is starkly apparent when it comes to the randomness of tornados. In covering this problem, Tornado God offers a masterful and extensively researched history of American theology pragmatically juxtaposed against the specific question of how religious thinkers deal with tragic weather disasters.

Thuesen's broad examination of American religion in its struggle with the problem of theodicy ranges from seminal thinkers such as Augustine, Aquinas and Calvin to modern theologians like Reinhold Niebuhr and Georgia Harkness. He describes their thinking on some of the basic questions that natural disasters bring forth. Are these things based in original sin? Does the creation of natural order bind God to necessity? Is God self-limiting? How does human free will and action enter into the question?

Thuesen offers no final answers to these theological questions, but they spur an insightful overview of American Protestant theology. Of course, the question of theodicy has vexed Catholic theologians, too. The book offers a fascinating study of humans' relationship with natural disasters, and the ideas it discusses are directly applicable to the problem of suffering in all aspects of life.