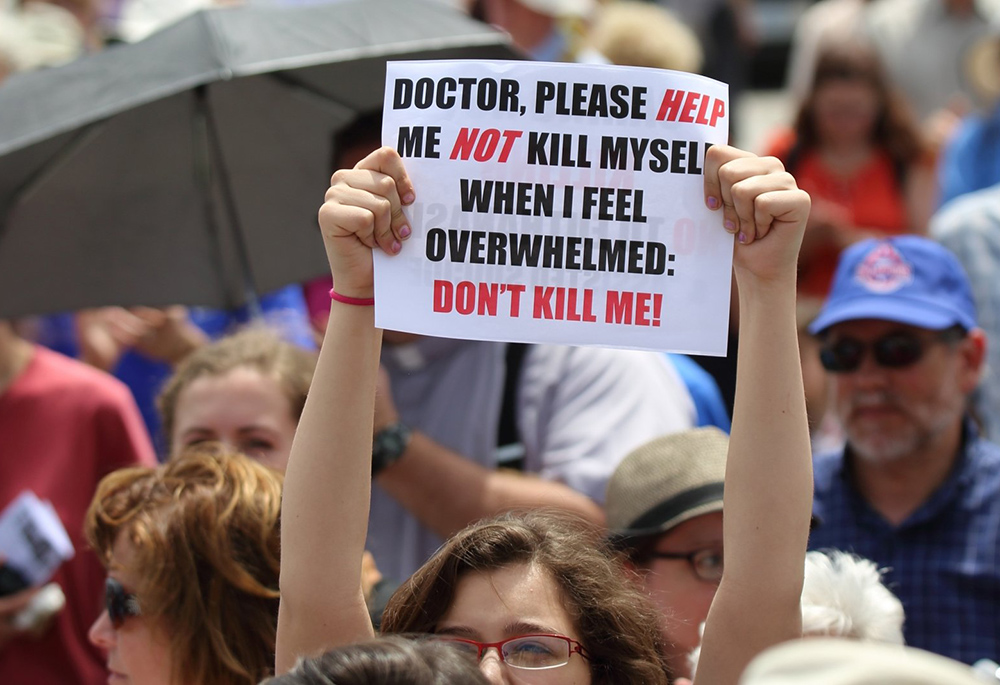

A woman is pictured in a file photo holding up a sign during a rally against assisted suicide on Parliament Hill in Ottawa, Ontario. (CNS/Art Babych)

Canada is engaged in an important, and sometimes frightening, debate about the right to life at the opposite end of the life spectrum from the debate going on here in the U.S. They are debating the widespread practice of euthanasia and whether or not the liberalization of euthanasia laws is in accord with the values their courts highlighted when they tossed out laws prohibiting the procedure.

In 2015, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled in Carter v. Canada that prohibitions against assisted suicide and euthanasia violated the fundamental rights of Canadian citizens. The court held that "An individual's response to a grievous and irremediable medical condition is a matter critical to their dignity and autonomy. The prohibition denies people in this situation the right to make decisions concerning their bodily integrity and medical care and thus trenches on their liberty. And by leaving them to endure intolerable suffering, it impinges on their security of the person."

In a phrase that is downright Orwellian, the Canadian court held that "the prohibition deprives some individuals of life, as it has the effect of forcing some individuals to take their own lives prematurely, for fear that they would be incapable of doing so when they reached the point where suffering was intolerable."

The resulting law, passed in 2016, has not yielded the lofty and noble results the Canadian court justices might have hoped, especially after an amendment further liberalized the law. In effect, anyone with a disability can ask to have her life ended.

Disability activists rightly understood that this has the effect of saying that their lives are not as valuable as the lives of those who are not disabled. "Our government’s efforts, particularly over the last few years, have been largely pushing forward on providing options to die as opposed to actually working to make things better and easier and more functional for disabled people," Jeff Preston, a Canadian with physical disabilities, said in 2020 when the law was being debated.

Human rights activists for the elderly and the poor, as well as the disabled, have argued that the Canadian system violates the rights of all three groups. They wrote that "reducing the number of required witnesses and accepting paid staff as independent witnesses" posed a real threat to "those without adequate support networks of friends and family, in older age, living in poverty or who may be further marginalized by their racialized, indigenous, gender identity, or other status." Such persons "will be more vulnerable to being induced to access MAiD [Medical Assistance in Dying]."

Advertisement

Tim Stainton, director of the Canadian Institute for Inclusion and Citizenship at the University of British Columbia, told the Associated Press that Canada’s law is "probably the biggest existential threat to disabled people since the Nazis’ program in Germany in the 1930s."

Some countries like the Netherlands, where euthanasia has been legal for 20 years, have monthly reviews of difficult cases, although it is hard to imagine a case that is not "difficult," and one wonders why the reviews are undertaken after the fact. Still, Dutch authorities have been investigating some abuses within their system and the Canadian system only has an annual review that follows trends.

And the trends are alarming: More than 10,000 Canadians died through euthanasia in 2021, a 32% increase over the previous year. 2020's numbers, in turn, represented a 36% increase over 2019.

Is this what the Supreme Court of Canada meant by "fundamental justice" when it issued its opinion in Carter v. Canada? The justices wrote, "The prohibition on physician-assisted dying infringes the right to life, liberty and security of the person in a manner that is not in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice." Is this an outcome that even resembles justice?

The linkage of human dignity with personal autonomy made by those advocating for assisted suicide is too facile. Personal autonomy and bodily integrity, which are not the same thing, are constitutive, not exhaustive, of human dignity. This moral fact pertains to the debate about abortion as well as euthanasia, and does so in complicated ways as pointed out recently by Boston College professor Cathleen Kaveny.

Advocates for persons with disabilities understand this acutely: The difference between their autonomy and their dignity is often the measure of their suffering. It is always the measure of society's compassion or indifference. That is one reason the Holy Father’s warning against a "throwaway culture" is so powerful: It strikes an obvious, albeit uncomfortable, moral truth.

What is more, our experience of life as a gift is real and culturally beneficial. The reduction of life's value to the exercise of autonomy leaves no room for notions of gift or grace. As well, Catholic ideas about the flourishing of individuals is always, always, always related to ideas about the common good. These are the two reasons why Catholics feel compelled to defend human life so profoundly.

No recourse to religious ideas is needed to be worried about this frightening development in Canada. The potential for coercion — familial, social or cultural — is frightening on its face and has been too little addressed in Canada. It seems impossible to declare that certain people should be allowed to end their life without suggesting that others like them should be encouraged to do so as well if they appear as a drain on the resources of a family or a society. This is Brave New World territory.

Assisted suicide is legal in 10 U.S. states, which is 10 too many. Death comes for us all. A society that embraces it, not as a reality but as a choice, is a society that is well on its way to becoming morally coarse.