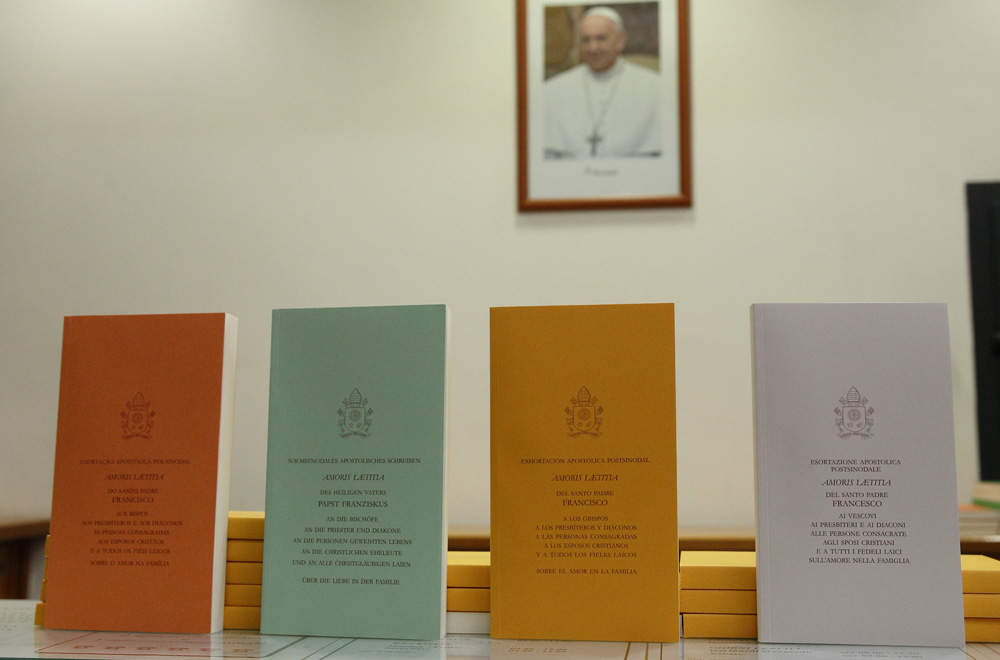

Copies of Pope Francis' apostolic exhortation on the family, "Amoris Laetitia," are seen during the document's release at the Vatican April 8, 2016. (CNS/Paul Haring)

When Pope Francis first issued Amoris Laetitia, the apostolic exhortation on marriage and family life, a little more than two years ago, I commented that as important as the text was, what really mattered is the texts it would spawn. That is, what would be the books and pamphlets that parish priests would be handing to couples preparing for their marriage, to families as part of their catechesis, and to those divorced and remarried Catholics who wanted to get right with the church? These would be the texts that would make Amoris Laetitia come alive.

We now have the first such text in English, Fr. Lou Cameli's just-published A New Vision of Family Life: A Reflection on Amoris Laetitia. As I have noted previously, Cameli attended the Boston College conference on Amoris Laetitia last autumn and it was there that I first heard him describe the exhortation as "a formation document."

Formation is the key to understanding the text and exposing the attacks on the document as so much foolishness. After providing a brief historical survey of church teaching on the family, Cameli writes, "In an unprecedented way, Amoris Laetitia directly addresses spiritual and moral formation. In fact, formation is at the center of its concern. This shift represents a pastoral conversion, perhaps even a revolution, in retrieving the centrality of marriage and family life in the transformative life and journey of faith for Christ's disciples."

Cameli then provides an annotated outline of the apostolic exhortation that is exceedingly helpful. Few people will read the entire document. Anyone whose knowledge of the text has been drawn from the headlines only knows about Chapter 8, which deals with divorce and remarriage. So, for example, in summarizing Chapter 5, "Love Made Fruitful," Cameli reflects on the importance of the extended family "that can move us beyond any form of isolating individualism." He discusses the fact that we remain sons and daughters even when we are grown, the importance of keeping the elderly integrated into family life so that the young may absorb their wisdom, the importance of siblings and, finally, how the "extended family can sustain and supplement the deficiencies of a nuclear family. It forms the family in a wider horizon." Think of the pressure that is now placed on a nuclear family! His synopsis of other chapters similarly shines an incisive and penetrating light on key aspects of family life as they are treated by the pope.

Next Cameli examines particular elements of formation: "Immersion in the Word of God"; "A reading of human experience"; "A sense of journey"; "The help of accompaniment, discernment and integration"; "Facing challenges;" and "Realistic hope." He writes that the list is not exhaustive but any pastor could easily use this as a road map. In discussing pastoral formation, he integrates key themes in the document; for example, he notes, "Those who bring formation to others certainly teach, but they also learn from those they teach. Similarly, those who are served will learn, but they also teach. This pattern reflects the reality of the Church itself as ecclesia discerns et docens, a church that both teaches and learns." There is nothing heterodox here, yet when reading the critics of the pope, I always get the feeling that their principle objection is that they think they already have all the answers and there is no need to do this whole dialogue and encounter business.

Those conservatives who have argued the pope is caving to the culture should consider Cameli's take on the challenge posed by our secular culture in the West. He writes:

The prevalent secularity is associated with a radical immanentism — in other words, an assertion that there is no reference point outside of this world and life as we know it. With that assertion, there are significant consequences for human behavior and decisions. If I really only have my world and myself, then that is the full measure of my life. That measure means a subjective and relative standard for establishing values and making decisions. When everything is relative, there is consequently no objective morality, nor is there a standard independent of my experience by which I could measure and evaluate my experience.

If the author of those words can see the clarity of the teaching in Amoris Laetitia, why can't its critics?

Of course, conservatives will not appreciate Cameli's examination of what he terms "Challenges Internal to the Life of the Church." Among these are "Residual Jansenism" and "Legalism" and "An ahistorical mentality." He is right on all scores, but the indictment's exactitude is precisely what will drive conservatives a little crazy.

Certain liberals will similarly be challenged by Cameli's discussion of conscience formation. Conscience is not a get-out-of-jail-free card. He reiterates the pope's important assertion that "We have been called to form consciences, not to replace them," but he also notes that the pope highlights the experience of distress as a starting point in his treatment of conscience. "Genuine distress is also absent when an individual rationalizes something that they clearly understand as wrong but then transform it into a good to be embraced. Pope Francis addresses this when he says, 'Naturally, if someone flaunts an objective sin as if it were part of the Christian ideal or wants to impose something other than what the church teaches, he or she can in no way presume to teach or preach to others; this is a case of something that separates from the community (cf. Mt 18:17). Such a person needs to listen once more to the gospel message and its call to conversion.' (Amoris Laetitia, 297)." As I have argued before, following on Newman, conscience is God's voice in our heart, not our own voice, a point a certain kind of Catholic has trouble distinguishing.

Advertisement

Cameli, in short, shows that Amoris Laetitia really is revolutionary in its understanding of Christian life, but it is not the repudiation of doctrine its critics claim, nor is it any kind of embrace of liberal sexual norms as some of its champions wish. The revolution is in its focus on formation as requiring more than the mere repetition of dogmatic formulas, important though those are, and in seeing such pastoral formation as a kind of evangelization for the baptized, that is, the very essence of what the church is and does. I expect within a very short time, this is the book that parish priests will be sharing with those seeking guidance from the church. I expect, too, that this focus on family life is really the last hope for the church in the West. If we do not embrace Amoris Laetitia, and implement it with the kind of wisdom Cameli shares in this book, it will be last one out the door turn off the lights.

[Michael Sean Winters covers the nexus of religion and politics for NCR.]

Editor's note: Don't miss out on Michael Sean Winters' latest: Sign up to receive free newsletters and we'll notify you when he publishes new Distinctly Catholic columns.