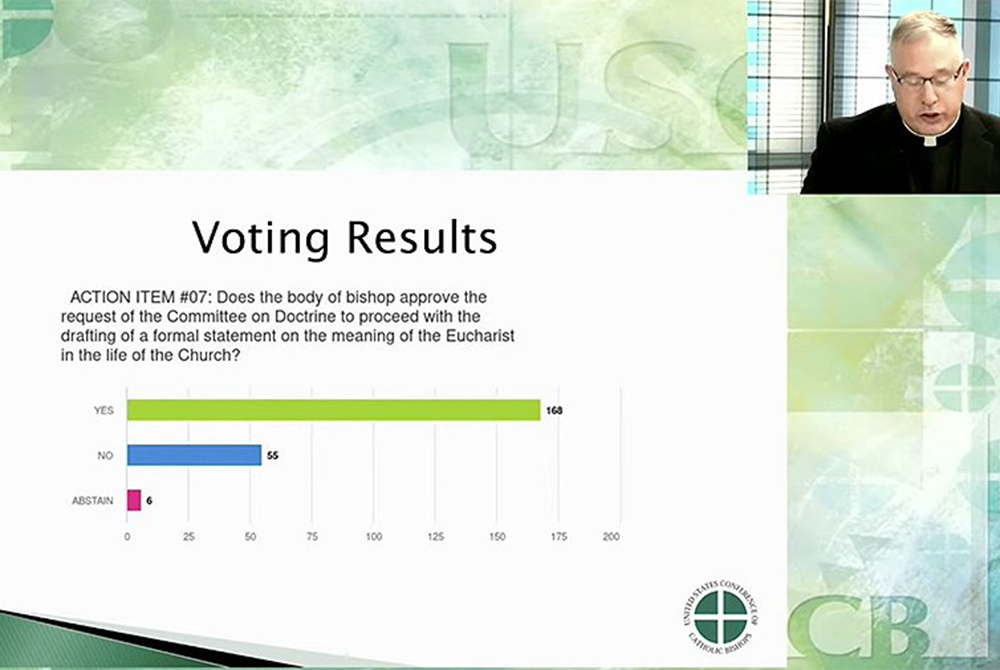

Msgr. Jeffrey D. Burrill, general secretary of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, reads voting results June 18, on a proposal that the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops' doctrine committee draft a formal statement on "the meaning of the Eucharist in the life of the church." Presented during their June 16-18 virtual spring meeting, the U.S. bishops approved it 168-55, with six abstentions. (CNS screengrab)

On Feb. 22, 1899, George Washington's birthday, Pope Leo XIII published his encyclical letter Testem Benevolentiae, condemning the heresy "Americanism." The document was balanced and the language was frequently indirect. It distinguished between what it called "political Americanism," those characteristics and national traits of the American people, which it commended, and "religious Americanism," the idea that America's democratic norms were for export, even for ecclesial structures, which it condemned.

Cardinal James Gibbons, the only American cardinal at the time who was primate in all but title, wrote to thank the pope for his letter but also to assure him that no one in the United States actually held the "extravagant and absurd doctrine." According to Gibbons, the entire controversy was the result of misinterpretations of American Catholicism in France, which was largely true.

Some archbishops echoed Gibbons, thanking the pope for the encyclical but assuring him no one believed the condemned propositions. Others wrote to thank the pope but did not say one way or another whether the heresy actually existed. Still others said nothing.

Archbishop Michael Corrigan of New York, always at odds with Gibbons, thanked Leo profusely for his timely and necessary condemnation.

It was the response from Archbishop Frederick Katzer of Milwaukee and his suffragans, however, that caused the greatest breach in the history of the U.S. hierarchy. Katzer not only praised Leo and affirmed that the heresy existed, he specifically expressed indignation at those who:

did not hesitate to proclaim again and again, in Jansenistic fashion, that there was hardly any American who had held [the condemned doctrines] and that the Holy See, deceived by false reports, had beaten the air and chased after a shadow, to use a popular expression. It can escape no loyal Catholic how injurious to the Infallible See and how alien to the orthodox faith such conduct is, since those erroneous opinions have been most assuredly and evidently proclaimed among us orally and in writing, though perhaps not always so openly; and no true Catholic can deny that the magisterium of the Church extends not only to the revealed truth, but also to the facts connected with dogma, and that it appertains to this teaching office to judge infallibly of the objective sense of any doctrine and the existence of the false doctrines.

Behind the elegant late 19th-century ecclesial language, Katzer was calling Gibbons a liar.

In my many years studying the history of the Catholic Church in this country, I have always considered the attacks on Gibbons to be the high point of episcopal disunity. They not only disagreed about the merits of differing approaches and arguments: Katzer impugned Gibbons' integrity. It was the lowest moment in the history of intra-hierarchic relations in the United States.

Until now.

What we witnessed last week at the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops' spring meeting was outrageous. As mentioned in my last column, bishops questioned each other's motives without any objection from the chair. Bishops argued that this push to draft a document on the Eucharist was not motivated by politics, but then had to acknowledge that the idea came from a working group formed to cope with the Biden administration. And, in what would appear funny were it not so tragic, every time the principals in the effort to draft the document explained that they were not motivated by politics, that this effort was not directed at any one individual, one of the culture warrior backbenchers would get up and mention President Joe Biden by name.

The final vote — the proposal passed 168 to 55, with six abstentions — could have gone the other way and the reasons to be disheartened would remain. The conference is a shambles.

If the president of the conference, Archbishop José Gomez, had a knack for leadership, he would have convoked a working group two weeks ago to hammer out a compromise. "That is leadership 101," said a seasoned church watcher. Alas, Gomez has no such knack.

Archbishop José Gomez of Los Angeles, president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, and Chieko Noguchi, the bishops' conference director of public affairs, hold a news conference at the bishops' conference headquarters in Washington June 16, the first day of the bishops' three-day spring assembly, held virtually due to concern over COVID-19. (CNS/Tyler Orsburn)

It is actually worse than merely a lack of leadership. Gomez showed the degree to which he was willing to try and manipulate the debate when he opened the meeting on Monday by reading a letter from Archbishop J. Augustine DiNoia, adjunct secretary of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. Gomez seemed to be suggesting that the letter was intended to support the effort to draft the document, even though the prefect of the CDF, Cardinal Luis Ladaria, had written a letter urging the bishops to slow down and have an "extensive and serene dialogue" before drafting any text.

As Gomez read the letter, it sounded like a form letter and, sure enough, it was. DiNoia told CNS' Cindy Wooden: "The letter contained a bland sentence that has received a lot of unmerited attention in the press: The congregation 'looks forward to the informal review of the eventual draft of a formal statement on the meaning of the Eucharist in the life of the church.' It would be helpful if you were to explain the utterly routine character of such communications."

DiNoia added: "Never has a letter of so little moment received such a level of unmerited attention. When we heard about the furor, we looked high and low for a letter bearing my signature that could possibly have created such a fuss. Finally, late this afternoon, we realized that they were talking about an 'accusa di ricevuto,' which we then located in the appropriate file."

So, either Gomez misrepresented DiNoia's letter intentionally, or he thought an "accusa di ricevuto" ("acknowledgement of receipt") was of some great significance. Either option required Gomez to think nothing of suggesting DiNoia was distancing himself from the prefect to whom he reports, a suggestion that is laughable. Either option shows the limits of Gomez's ability to lead the bishops' conference at this important time.

The time is not important only because of this lousy proposal to find a way to deny Biden Communion. It is important because the Holy Father has called the universal church to engage in a synodal process. How will Gomez be able to manage a synodal process?

Advertisement

Two years ago, the Amazon synod voted to ask Pope Francis to permit the ordination of older, chaste men as priests, viri probati, by a margin of 128-41 and to support additional discussion of the ordination of women deacons by a vote of 137-30. Pope Francis did not authorize the ordination of viri probati or women deacons in his post-synodal document Querida Amazonia. As Jesuit Fr. Antonio Spadaro related at Civilta Cattolica the Holy Father understands that 128 bishops can be wrong or, to put it differently, that a synod must discern, not merely decide by majority or even super-majority vote. He told Spadaro:

There was a discussion [at the 2019 Synod] ... a rich discussion ... a well-founded discussion, but no discernment, which is something other than arriving at a good and justified consensus or relative majority. […] We must understand that the Synod is more than a parliament; and in this specific case the Synod could not escape this dynamic. On this issue the [2019] Synod was a rich, productive and even necessary parliament; but no more than that. For me this was decisive in the final discernment, when I thought about how to write the exhortation [Querida Amazonia].

Does the leadership of the U.S. bishops' conference understand that there was no synodality last week at their meeting? No discernment of the Holy Spirit? The meeting, instead, resembled a high school-level debating society. It is too depressing. And it is not likely to change anytime soon.