A man holds a sign in support of U.S. President Donald Trump before an impeachment vote on Capitol Hill in Washington Dec. 18, 2019. (CNS/Reuters/Tom Brenner)

Trying to predict what will happen in the political life of the nation in any year is more or less a fool's errand, but in 2020 the task is even more perilous than usual. But I'm always happy to play the fool, so here is what I will be looking for politically in the new year.

The Senate trial of President Donald Trump commands the political landscape the way the dome of the U.S. Capitol dominates the D.C. skyline: It casts the longest shadow in town. Most analysts believe we already know the outcome, that Sen. Majority Leader Mitch McConnell will control the proceedings such that no further incriminating evidence will be forthcoming and the Senate will vote to acquit. As is, the polls show a divided nation, and McConnell and the Republicans believe they will face no blowback if they vote to acquit the president.

We also know that if anyone with additional incriminating evidence was going to come forward, they would have by now. Unless what has been missing is applied by the Senate: compulsion. It was one thing for acting White House Chief of Staff Mick Mulvaney to decline to testify before the House Intelligence Committee, and McConnell has indicated he does not intend to call such witnesses. But the Senate trial has one quality the House proceedings did not and which McConnell cannot entirely control: The chief justice of the United States will be on hand to make procedural rulings. If Chief Justice John Roberts orders Mulvaney to testify, or even more likely, former National Security Advisor John Bolton, their testimony could be explosive. Short of having something that bears a striking resemblance to a smoking gun, the Senate will vote to acquit, and the president's decision to publish the actual smoking gun, the transcript of his call with the president of Ukraine, will have been vindicated.

His decision vindicated, yes, but not himself. The president likes to paint himself as a victim, and not just any victim but the most victimized president of all time, at least when he is not portraying himself as a victor, and not just any victor, but the winningest victor of all time. This discordance may not upset his base. The psychology of people who resent change and the success of others, and who also feel entitled to success, such people can easily embrace this strange victim/victor combination as their champion. Still independent voters decide elections, and I can't imagine that they warm to this bifurcated personality.

If the impeachment saga is likely wound up by the end of January, the Democratic nominating process could well be completed by March 4. Super Tuesday, March 3, is really super this year, with the addition of California and Texas, meaning that more than a third of all delegates will be awarded on that day. If any candidate emerges with even a lead of 100 or so delegates, it will be hard to catch them given the proportional representation that distributes delegates evenly.

In order to win on Super Tuesday, a candidate needs to pick up some momentum in February when Iowa, New Hampshire, Nevada and South Carolina Democrats go to the polls. Barring some unforeseeable event, there are four major candidates — former Vice President Joe Biden, Sens. Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, and former Mayor Pete Buttigieg — and any one of them could win Iowa or New Hampshire. If anyone wins both, it will be hard to stop them. Iowa and New Hampshire are overwhelmingly white, but Nevada has a significant Latino vote, and African-Americans will be a majority of the electorate in South Carolina.

Advertisement

Potential Democratic voters tell pollsters that their No. 1 objective is to select someone who can defeat Trump in November. So far, the centrists have won that argument, even though you have to go back to the 1964 campaign of Barry Goldwater and the 1972 campaign of George McGovern to find an election where the winner was the person cast as a moderate facing an extremist. Ronald Reagan was considered extreme, and Democrats hoped he would be the nominee in 1980, a hope they lived to regret. In 2004 and in 2012, John Kerry and Mitt Romney won their party's nod largely because they were viewed as the person best able to defeat the incumbent, and they both lost.

I predict that the polls are wrong, and that Democrats will embrace the person who does best in the debates immediately preceding the voting. I will venture one more projection in regard to the Democrats: No matter who wins, the nominee will embrace the wealth tax first put forward by Warren. It is popular even with Republicans.

Almost as important as the presidential contest will be the fight for control of the Senate. There are 35 seats up for election, two more than usual because there are special elections in Arizona and Georgia. Twenty-three of those seats are held by Republicans against only 12 by Democrats. Democrats need to pick up three seats for control of the Senate if they also win the presidency, and four if they don't. Most commentators identify Arizona, Colorado, North Carolina and Maine as toss-ups. Michigan leans to the Democrats, but a Trump victory could flip that seat. Alabama and Iowa could flip the other way if Trump loses badly. It is far too soon to predict the outcome in these races.

Candidates during the first official Democratic 2020 presidential primary debate in Miami June 26, 2019: New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio; U.S. Rep. Tim Ryan of Ohio; Julian Castro, former mayor of San Antonio; U.S. Sen. Cory Booker of New Jersey; U.S. Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts; former U.S. Rep. Beto O'Rourke of Texas; U.S. Sen. Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota; U.S. Rep. Tulsi Gabbard of Hawaii; Washington Gov. Jay Inslee; and former U.S. Rep. John Delaney of Maryland. (CNS/Reuters/Mike Segar)

The next major political development will fly beneath the radar screen. Sometime in June or July, attitudes about the economy will begin to solidify. Back in 2012, Nate Silver addressed the problem of using economic data when devising models to predict voting behavior, noting that there is a lag time between when voters get the information and the impact it has on voting. Revised economic data is not useful if the revisions happen after voters have formed their judgment. (NB: Read the entire article to learn about the complicatedness of devising these models.)

In 1992, it turns out the economy was not nearly as bad as Bill Clinton painted it. Silver writes:

The initially reported data, meanwhile, is also what is available to candidates and voters at the time of the election. Some econometric models score the 1992 election as a "miss," because revised economic data shows roughly average growth during that year, when the incumbent, the elder President Bush, was defeated. However, the data was still quite poor as it was reported during 1992 itself.

It is shocking that Trump's approval ratings are so dismal when the economy is firing on all cylinders. If it slows down, or is perceived to be moving in the wrong direction, those numbers could really tank.

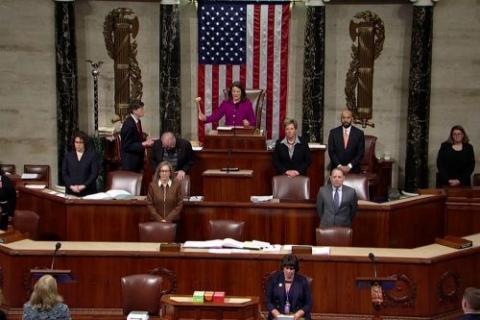

Rep. Diana DeGette, D-Colorado, pounds the gavel to open the session to discuss rules ahead a vote on two articles of impeachment against U.S. President Donald Trump on Capitol Hill in Washington Dec. 18, 2019. (CNS/Reuters/House TV)

We also can expect GOP efforts to restrict voting and remove people from the voter rolls to intensify in the summer, with a series of court battles that could be frightening. We also will get a Supreme Court ruling in the case June Medical Services v. Gee regarding a Louisiana law that will restrict abortion access in that state. None of us knows if the court will decide the case narrowly or, as it did in Citizens United vs. FEC or Janus v. AFSCME, decide to overturn a long-standing precedent. But the one thing they will not do is expand abortion rights. The decision, whatever it is, will be seen as a win for pro-life legal advocates and it will push the Democrats into hardening their opposition to any restrictions on abortion even more. The backlash will be enormous, and it gives me no joy to predict that it will energize the angry pro-choice groups more than it does the satisfied pro-life groups. If the Democrats win in November, pro-choice groups will take the credit even if the nominee is someone like Sanders or Warren who wake up in the morning eager to take on economic interests, not to fight culture wars. No matter how it all plays out, the country will continue to be divided on the issue.

In the summer, we all get to take a break as the party conventions have turned into snooze-a-thons and the Tokyo Olympics, which runs from July 24 to Aug. 9, can potentially provide a bit of national uplift and unity. Some tiny gymnast or big pole vaulter or swimmer will bring all Americans to their feet. I hope Trump doesn't crash them and, therefore, spoil them.

Autumn will bring the debates and the election. There is one irony to Trump's divisiveness that shows how little we humans grasp our circumstances. For years, Democrats have pledged to energize more voters and get them to the polls. Republicans, on the other hand, have tried to make it harder for people to vote. But it is Trump who has energized the electorate even as he has divided it, and we can look for a record turnout in November. I hope he loses, but I also hope he loses big. What scares me more than him winning a second term is the prospect of him losing narrowly, and how he might react. That could be the constitutional crisis of 2020, not the impeachment that kicks off the new year.

So those are the political items I will be looking at in the year ahead, and I hope you, dear reader, will join me. Tomorrow, what to look for in the church in 2020.

[Michael Sean Winters covers the nexus of religion and politics for NCR.]

Editor's note: Don't miss out on Michael Sean Winters' latest. Sign up and we'll let you know when he publishes new Distinctly Catholic columns.