Pope Francis poses with people during his general audience in Paul VI hall at the Vatican Jan. 29. (CNS/Paul Haring)

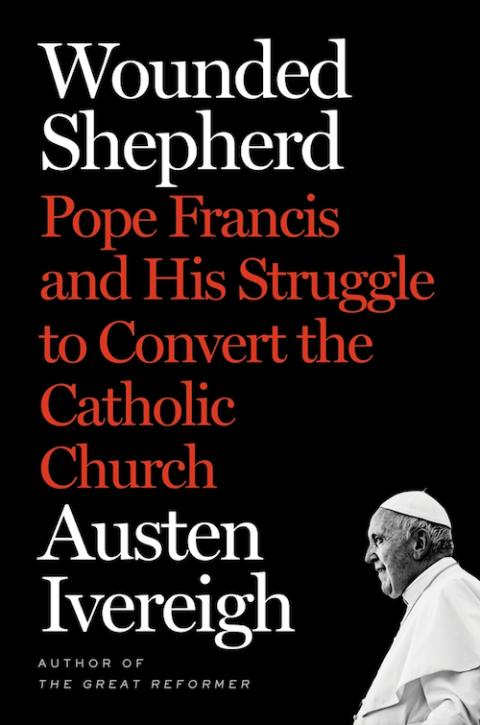

Next month, we will celebrate the seventh anniversary of the election of Pope Francis. In some ways, it is hard to remember what we were feeling before it became obvious that this first pontiff from the Americas would be a reforming pope. In other ways, it seems like yesterday that Pope Benedict XVI resigned from his office and flew off to Castel Gandolfo. And, so before we start the looks back and looks ahead for this anniversary's occasion, it is good to ground ourselves. Fortunately, at hand is just the book to do it, Austen Ivereigh's Wounded Shepherd: Pope Francis and His Struggle to Convert the Catholic Church.

Just as Ivereigh's 2014 biography The Great Reformer: Francis and the Making of a Radical Pope helped many of us better understand what experiences had formed the new pope before his election, this new book provides a much needed, lucidly written, look at the past seven years. Remarkably, he does so in part by taking a swipe at his earlier biography! At a June 2018 meeting, the pope warned Ivereigh against the "great man" myth in writing his book:

I realize now that 'The Great Reformer' contributed to that myth, written in the dizzying first months of his pontificate, the parallels with his life — how he appeared at moments of crisis in the church — offered an irresistible narrative: cometh the hour; cometh the man. I cringe now that I even likened him to a gaucho riding out at first light.

Okay, okay: The gaucho reference was cringeworthy. But, Ivereigh's biography, combined with Elisabetta Piqué's Pope Francis: Life and Revolution were indispensable early volumes that helped the rest of us understand Jorge Maria Bergoglio's life before March 13, 2013.

I suspect that Chapter 5 of the current volume will be the one that most engages an American audience, as it focuses on the pope's real conversion on the clergy sex abuse issue. At first, the pope had received lousy information about the situation in Chile. After he was faced with ongoing and credible objections, he dispatched Archbishop Charles Scicluna to investigate, and Scicluna documented the depth of the problem and how wrong the pope had been. The pope took this very public self-correction to heart. Ivereigh writes:

But the shock and shame of this realization also forced the pope to see the abuse and its cover-up in a radical new light, as the symptom of something much more profound — and diabolical. It was the corruption of power linked to benefaction, the twisting of power for service into power to exploit, a perversion of the very mission entrusted to the Church by Christ — to defend the vulnerable from the wolves.

Francis demanded the entire episcopate of Chile come to Rome for a group retreat, met with the leading victims beforehand and then invited the Chilean bishops to recognize how God was at work in the current mess, and through whom God was speaking, namely, the victims of the abuse. Ivereigh looks back to an earlier essay Bergoglio had written in 1984 entitled "On self-accusation," where the future pope had written, "Whoever accuses himself makes space for God's mercy." The Chilean bishops presented their resignations en masse to the Holy Father.

Advertisement

Pope meets with Chilean bishops, discusses abuse crisis

What is remarkable is the degree to which Francis — once he recognized how badly he had misjudged the situation in Chile — threw the weight of his papacy into the fight against clergy sex abuse. Also remarkable is the vast difference between the pope's spiritual approach and the managerial, legalistic approach first adopted by so many Americans, bishops and laity, conservative and liberal. The pope was not content, however, to wash the outside of the glass. He had seen the filth inside, too.

Chapter 6 is even more compelling, as Ivereigh looks back to Bergoglio's time in San Miguel, Argentina, where he served as rector of the Colegio Máximo de San José. The future pope founded a large parish alongside the school, and the seminarians were formed as missionaries in the barrios served from that parish. It was here that Bergoglio developed his understanding of missionary discipleship in which the acids of modernity were not condemned, nor met by erecting new walls, as happened in so much of the West. No, the answer Bergoglio imparted to the students in his care, was that evangelization consisted of accompanying the marginalized.

Austen Ivereigh attends a news conference after a session of the Synod of Bishops for the Amazon at the Vatican Oct. 22, 2019. (CNS/Paul Haring)

"[W]hat seems most to matter about the mission isn't what the young went out to give but what they have brought back," Ivereigh writes. "It's a sense of belonging, of oneness. That the Kingdom of God is born in kinship and service. That God is acting there. That Grace abounds. That, as Cardinal Bergoglio put it in 2011, 'God is present in, encourages, and is an active protagonist in the life of His people.' "

These themes would form the centerpiece of the Aparecida document that emerged from the 2007 continent-wide meeting of the Latin American bishops' conference, a document that Bergoglio helped draft. The insights, when shared with his brother cardinals before the conclave of 2013, are what led those cardinals to turn to him as the next pope. The text would, in turn, inform his first apostolic exhortation as pope, Evangelii Gaudium.

I note, as well, that Bergoglio's decision to place a parish smack in the middle of the college, and to make it such a central focus of formation, echoes an early discussion within the Society of Jesus, related in Jesuit historian Fr. John O'Malley's book The First Jesuits. St. Ignatius permitted the expansion of Jesuit schools, first in Gandia, Spain; Messina, Italy; and Palermo, Italy. They had to be exempted from the order's vow of poverty: Other houses would need to continue to beg alms, but these colleges could be endowed. But Ignatius required a church be attached to all colleges, 35 of which had opened by the time of Ignatius' death. The ministry of education was not to be completely divorced from the more pastoral ministries of preaching and caring for the sick and dying the order undertook.

The chapter on Francis' efforts to reform Vatican finances was especially helpful to me. I find financial matters opaque, from the International Monetary Fund to my checkbook. Consequently, when there is a news item about financial changes at the Vatican, I confess I do not always make it to the end of the story. Ivereigh explains the hurdles that have been overcome, the ones that remain, the key players and how these reforms fit into the broader effort to convert the church that Francis has undertaken.

The rest of the book is similarly informative and exceedingly well written: Once you start, you do not want to put this book down. I would tell you more, but then you would not have to buy the book — and you should.

Some historians may complain about the fact that Ivereigh footnotes journalists whose sources are not always on the record, and when documentation is not available. In this, as well as other respects, Ivereigh's book put me in mind of Peter Hebblethwaite's biographies of Popes John XXIII and Paul VI, which is very high praise. Too many historians have spent too much time writing books that may be heavily documented but which are virtually unreadable. This is not that book.

(Henry Holt and Co.)

What will be most challenging for NCR readers is this: What Francis means by reform is quite different from what the Catholic left in the U.S. has been advocating. He does not intend to replace a set of conservative rules with a set of liberal ones. He wants the whole church to think about the place of rules within the life of the church, and to stop overemphasizing that place. He is suspicious of the application of social science methodologies to the life of the church. He grasps that no rearrangement of structures will be enough if the church as a whole does not have an experience of conversion, setting aside our agendas to see what the Spirit is trying to accomplish here and now.

Seven years into a pontificate, sometimes, even usually, there is a sense that whatever dynamism existed at the beginning is now wearing off, efforts at reform stall, old habits return. Ivereigh paints a different picture, of a pontiff whose woundedness, not only in the sex abuse crisis but especially there, has brought new energy to his efforts, and a conviction that his own conversion is also the kind of conversion the church needs. If Ivereigh is right, buckle up, because the best is yet to come.

[Michael Sean Winters covers the nexus of religion and politics for NCR.]

Editor's note: Don't miss out on Michael Sean Winters' latest. Sign up and we'll let you know when he publishes new Distinctly Catholic columns.