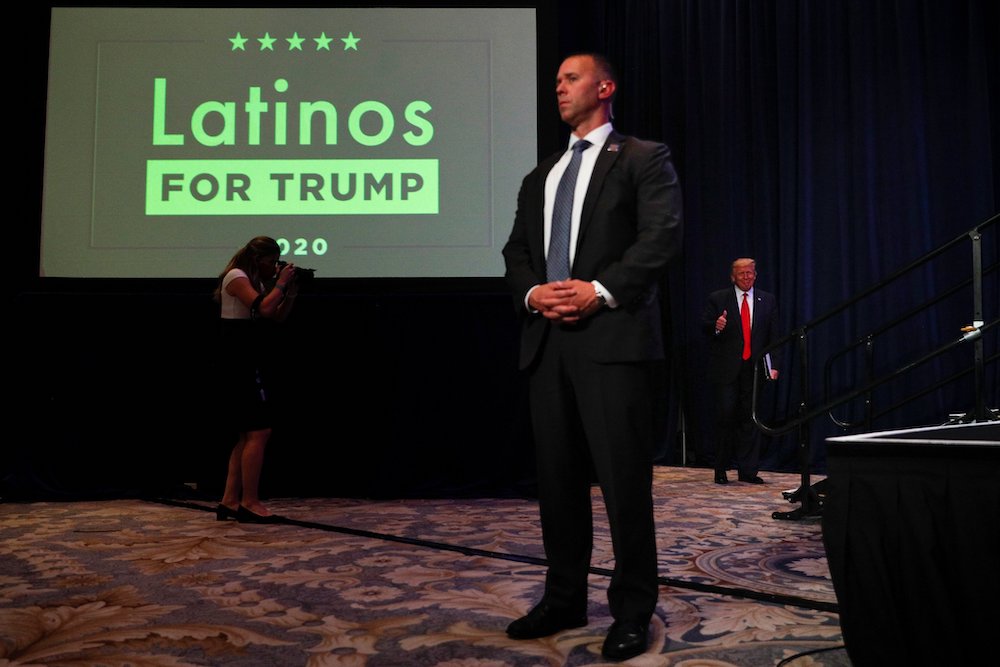

President Donald Trump, right, walks on stage before delivering remarks during a Latinos For Trump campaign event at the Trump National Doral Miami resort in Doral, Florida, Sept. 25, 2020. (CNS/Reuters/Tom Brenner)

Editor's note: This week, NCR political columnist Michael Sean Winters looks at the Latino vote in the 2020 election and what it portends for the future of American politics. Read Part 2 here.

Election Day 2020 began with the polls pointing to a dominant victory for Joe Biden and the Democrats. Biden was leading in Florida and barely trailing President Donald Trump in Texas. Texas! By 11 p.m., of course, both states were decisively in the Trump column, and the election was so close, The Associated Press did not call it until the following Saturday.

Setting aside the fact that we now know polling is often a lot more like astrology than astronomy, nothing was more surprising on election night than the results that were coming in from Miami-Dade County in Florida and from the Rio Grande Valley in Texas. Some had speculated that Trump would do better in Miami-Dade because of the GOP messaging that targeted Democrats as socialists, but no one predicted such an enormous change in the vote totals. And the Rio Grande Valley, when it was mentioned at all, was always seen as a Democratic stronghold.

In 2016, Hillary Clinton trounced Donald Trump in Miami-Dade, with 63.22% of the vote to Trump's 33.83%. In 2020, Biden actually got fewer votes than Clinton had, and Trump improved his vote total by almost 200,00 votes, from 333,999 in 2016 to 532,833 in 2020. Biden captured only 53.31% of the vote in Miami-Dade to Trump's 45.98%. According to the county's website, the population is 71.51% Hispanic.

In the Rio Grande Valley, something similar was unfolding. Brownsville and McAllen have none of the glitz of Miami. The people are poor and they are overwhelmingly Catholic. Mexico is the nation of origin for most of its citizens, although a Latino friend likes to remind me that many Hispanics in Texas did not cross the border: The border crossed the towns in which their ancestors lived when the U.S. annexed Texas.

For all the differences between Florida and Texas, Trump continued to overperform his 2016 numbers by significant margins in the Rio Grande Valley. In Cameron County, home to Brownsville, Biden garnered 56.11% of the vote, down from Clinton's 64.10% in 2016. Trump's share of the vote grew from 31.80% four years ago to 42.94% in 2020. In next door Hidalgo County, home to McAllen, Trump's share of the vote grew from 27.89% in 2016 to 40.98% in 2020.

Advertisement

And the questions Trump's surprising showing raises are not merely of historical interest. "Since the 2010 census — we'll soon have the 2020 numbers — 94% of Latinos under the age of 18 were born in the United States," notes University of Notre Dame political science Professor Luis Fraga, who also directs the school's Institute for Latino Studies. While the Black population of the U.S. is stable in the low teens, the Latino population is exploding. According to the Pew Research Center, Latinos in 2019 constituted 18% of the population, up two points from 2010.

In the wake of the election results, commentators scrambled for reasons to explain why Trump, so long tarred as a racist whose hostility to immigrants was one of his defining characteristics, improved his margins among Hispanics by such significant numbers.

At Politico, Jack Herrera argued that in the Rio Grande Valley, Trump had scored well among Tejanos, not Latinos, that is to say, that the pollsters and national commentators were guilty of a fundamental category mistake. He wrote:

Though not everyone in the Rio Grande Valley self-identifies as Tejano, the descriptor captures a distinct Latino community — culturally and politically — cultivated over centuries of both Mexican and Texan influences and geographic isolation. Nearly everyone speaks Spanish, but many regard themselves as red-blooded Americans above anything else. And exceedingly few identify as people of color. (Even while 94 percent of Zapata residents count their ethnicity as Hispanic/Latino on the census, 98 percent of the population marks their race as white.) Their Hispanicness is almost beside the point to their daily lives.

The Trump campaign succeeded because it did not see all Latinos as one big demographic, animated by shared experiences of racism. "His campaign spoke to them as Tejanos, who may be traditionally Democratic but have a set of specific concerns — among them, the oil and gas industry, gun rights and even abortion — amenable to the Republican Party's positions, and it resonated," Herrera wrote.

Volunteers from Hope Border Institute in El Paso, Texas, register voters in mid-September as they wait in line in their cars for food distribution. (CNS/Courtesy of Hope Border Institute)

Ethnic identity is a lot more complicated than what box gets checked on a census form and, what is more, the culture of south Texas is, in many ways, deeply conservative at least on cultural issues. On economic issues, liberal populism sells as well as its conservative iteration, and Sen. Bernie Sanders won both Cameron and Hidalgo counties during the 2020 primaries.

Marc Caputo, also writing at Politico, modified and expanded Herrera's analysis, noting that Trump improved his numbers among Puerto Ricans in Philadelphia and Mexican-Americans in Milwaukee, not just conservative south Texas and among wealthy Latinos in Miami. Trump even outdid his 2016 numbers in the New York congressional district represented by U.S. Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

Caputo argues that the same culture war appeals that Trump employed to entice white working-class voters worked as well with working-class Latinos. And the Democrats played into their hands, according to Caputo:

And then there's the way the left spoke — or were framed by Trump's campaign for speaking. Calls to "defund the police," a boycott of Goya Foods and the threat of socialism turned off some Latino voters. And even using the term Latinx to describe Latinos in a way that's gender-neutral only served to puzzle many Hispanics.

He notes that a Pew poll found that 97% of Hispanics do not use the term "Latinx." Most had not even heard of it.

If all that was not enough, voters in south Florida were exposed to an intense disinformation campaign on social media.

Joshua Blank, research director at the Texas Politics Project at the University of Texas, warns against placing too much focus on the Rio Grande Valley results at all. "It is an extremely tiny share of Texas' population, which combines with historically low turnout, so large variations are more likely."

Latino voters in the Maryvale neighborhood of Phoenix line up at a polling station to vote in the presidential election Nov. 3, 2020. (CNS/Reuters/Edgard Garrido)

In Arizona, by contrast, the Latino vote pushed Biden across the finish line, flipping the state that had not voted for a Democratic presidential candidate since Bill Clinton narrowly outpolled Bob Dole in 1996. Prior to that, Harry Truman was the last Democrat to win the state. The UCLA Latino Politics and Policy Initiative looked at voting data from the 2020 election and concluded that Biden took 75% of the Latino vote in Maricopa County, which accounts for 60% of the state's population. Unlike in many other parts of the country, a Democratic grassroots effort to get out the vote knocked on one million doors in Arizona, which might have accounted for Biden's win.

"Since 1972, when pollsters started separating out Latino voters, an average of 28.4% of Latinos will vote for any Republican candidate," noted Notre Dame's Fraga. "And there is always some variation. Bob Dole only got about 20%, but George W. Bush got 40%." He added, "The question is not if there is a Latino vote. There is a real 70-30 split. That is not the same split you find in the African American community or the white community."

University of Texas' Blank told NCR he did not put too much stock in much of the early analysis. "What most people said was a mix of incomplete analysis and 'motivated reasoning,' " he said euphemistically. "There is no accurate way to describe a 'Latino vote' at the national level. Texas is more homogenous than most, and even here there is a wide diversity of socio-economic and cultural realities."

Blank and Fraga both agree that the 2020 election proved to all political commentators what those who have dug deeply into Latino voting patterns and attitudes have known all along: The Latino vote is not a monolith, and Hispanics from different countries, living in different kinds of neighborhoods, with different levels of education and affluence and different ideological dispositions will always be misunderstood by campaigns and the commentariat if they are indiscriminately lumped together.

It is said of "the Catholic vote" that it no longer exists and that Catholics always pick the winner. Turns out the Latino vote is becoming something similar. In a polarized electorate, whichever party can best motivate a younger population whose political attitudes have not hardened, whose electoral participation rates have been low, but who are an increasing share of the population in key swing states, is the party that is going to win. And in America, elections are won at the margins, so small differences in a few key precincts can make all the difference.

On Wednesday: Latino identity and voting