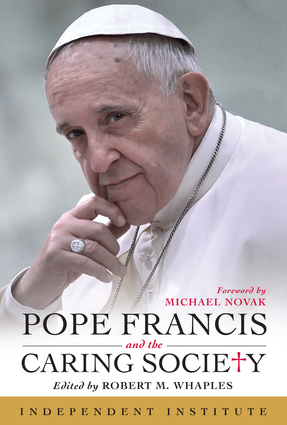

Pope Francis holds a copy of his apostolic exhortation, "Evangelii Gaudium" ("The Joy of the Gospel"), April 29, 2014. In it he laid out his vision for his pontificate, saying he prefers a church that reaches out to people on the streets rather than a church that is confined to its own concerns. (CNS/Paul Haring)

One of my best friends sent me the book Pope Francis and the Caring Society, edited by Robert M. Whaples and with a foreword by the late Michael Novak. Having read it, I see this gift was intended as a Lenten penance. The book was published by the Independent Institute, a self-described think tank, but, as this book demonstrates, it would be better described as a factory for libertarian propaganda. The only value in this book is it unintentionally demonstrates the degree to which certain Catholic libertarians are so drenched in free market ideology that it was them I thought of this past Sunday when we heard the Lord God prohibit the Israelites from committing idolatry. They do not idolize money. They idolize their ideology. The results are, unsurprisingly, sad or worse.

That foreword by Novak is well dog-eared, but I shall follow the maxim de mortuis nil nisi bonum and ignore it. The introduction by the editor highlights the tone of the volume. So, when Francis is quoted as denouncing "slave labor" after 700 workers were killed in an unsafe factory in Bangladesh, Whaples asserts the pope was speaking "hyperbolically." I wonder: If 7,000 had been killed, instead of only 700, would it still be hyperbole? Or was it that the 700 were in Bangladesh and had no expectation of a safe working environment: Had the 700 dead been in Bentonville, Arkansas, would it be hyperbole? NB, I do not select Bentonville on account of its alliterative value but because it is home to Walmart, which brings the products of the world's slave labor to a store near you!

Whaple's attempts to be even-handed and presents what he thinks are capitalism's strengths and its weaknesses, but what he does not grasp — and what no one in this entire volume grasps — is that the church's critique of capitalism, like its critique of Marxism, is not an economic critique. It is not even a mere ethical critique, although it bears such ethical concerns, too. It is at the deepest level, the anthropological level, where we consider what we mean when we say the words "human person," when we consider what we can and cannot expect of life, what we mean by justice; it is at this level that contains an experiential as well as a philosophic component, it is here that the Catholic must part ways with the capitalist as she must part ways with the Marxist. Throughout the volume, the pope is chided for not understanding economics, as if that were the heart of the matter. It isn't.

Samuel Gregg, the research director at the Acton Institute, has a chapter called "Understanding Pope Francis." He charts the unhappy history of Argentina in the 20th century, how it went from "riches to rags," and how the culprit was really political manipulation and constriction of the free market, mostly at the hands of Perón and his followers. He allows that the collapse of the Argentine economy in the late 1990s, and the intense suffering of its people, is laid at the feet of neo-liberal economics by most Argentines, but Gregg thinks the failure to cut government spending and mishandling of currency convertibility played a role. Somehow with these guys, it is never capitalism's failure that causes the human suffering, always the failure to be capitalist enough! As I say, the ideology itself is the golden calf that must be worshipped.

I got a kick out of Gregg's attempt to explain and to question the "theology of the people" that has so shaped the Catholic Church in Argentina and the thinking of Francis specifically. He frets about "the reality that you are likely to find different views on numerous subjects among any group denoted as el pueblo. Recognizing this multiplicity becomes more difficult if millions of individuals are simply placed into one catch-all category." Huh? Does Gregg not think a people, any people, develop a culture that distinguishes them from other cultures? The fact that you find some Italians who are celibate does not diminish one's ability to recognize the sensuality of Italian culture. There may be such a thing as an ungenerous Puerto Rican, but I have never met one, so I conclude with confidence that Puerto Rican culture puts a premium on generosity of spirit. Etc.

Normally you would expect an essay by Gregg to be the worst in any volume. Sadly, by comparison to the other essays in this tome, Gregg's is one of the more sane contributions. Gabriel Martinez of Ave Maria University writes about markets and oligarchy. He writes, "Pope Francis has insisted that Evangelii gaudium must be read in the context of Catholic social teaching. The most immediate context is the teaching of John Paul II." What about Pope Benedict? He wrote a social encyclical, too. Later, Martinez observes, "In the ideal, abstract system that informs our ideology and political advocacy, market competitors face each other as approximate equals, as in sports and board games." Who is the "our"? Later he writes, "One way to characterize such a society is to call it an 'inclusive society.'" Or an antelope, for all the arbitrary, bizarrely argued claims in this essay. Who writes like this?

Nothing prepared me for the commentary on Francis, capitalism and charitable giving that is the subject of an essay by Lawrence McQuillan and Hayeon Carol Park. That they are libertarian ideologues of the highest order is evident from statements like this: "The redistribution advocated by Francis appears to violate the commandment 'You shall not steal' because government redistribution always and necessarily involves force or coercion." They criticize Francis for citing St. John Chrysostom's famous dictum: "Not to share one's wealth with the poor is to steal from them and to take away their livelihood. It is not our own goods which we hold, but theirs." This, they claim, "encourages a war of one class against another. … In contrast, charitable giving within a capitalist economy is voluntary. Capitalism is first an expression of giving." Wow. Ever heard of justice?

Advertisement

Odd to say, it is not only the craven ideology of this essay that frightens. This is the most juvenile thing I have read in print in years. They write:

[The pope] is guilty of the vice of vagueness, which is no substitute for knowledge and leaves the pope espousing nothing but what he sees as good intentions. Christians have long taught that faith alone is not sufficient for temporal matters such as economics — reason and knowledge are necessary. Indeed, Catholic theologians see faith and reason as complementary, and the phrase faith and reason is often associated with Catholic discussions of science, economics, and other "worldly" disciplines.

Really? Faith and reason are associated with Catholic thought? Who knew? Someone should tell the pope this.

Later, they focus on "a document titled the Aparecida." Do they know it is a place? Later, they write: "History demonstrates, however, that redistribution motivated by 'social justice' ultimately leads to totalitarian government, as Nobel laureate economist Friedrich A. Hayek explained many years ago." Now, it is Lent, and in addition to giving up ice cream, I pledged to try and be less judgmental. But a journalist's first obligation is not to be nice but to be truthful, and in reading that last sentence, I made the note in the margins, "Was the first draft of this essay done in crayon?"

Philip Booth's essay on "Property Rights and Conservation" raised some interesting points, and he acknowledges and wrestles with the fact that in our Catholic tradition, we recognize that the right to private property is a consequence of the fall. And, in the best traditions of casuistry, which has gotten a bad name it doesn't deserve, he explores the value of linking our worst human aspirations to our best. But still, at times he tries and wiggles the vice of self-interest into a virtue, which is the first, fatal step towards becoming an apologist for capital.

Booth's essay notwithstanding, this is a bad book, one that Catholics who actually know anything about our social doctrine will find depressing or laughable depending on your mood. Its real value is that it unintentionally demonstrates the degree to which many Catholics, in well-funded institutions, are guilty precisely of the idolatry of the market Francis has condemned. If you thought the pope's words were hyperbolic, this book will convince you they are not.

[Michael Sean Winters covers the nexus of religion and politics for NCR.]

Editor's note: Don't miss out on Michael Sean Winters' latest: Sign up to receive free newsletters, and we'll notify you when he publishes new Distinctly Catholic columns.