Los Angeles Archbishop José Gomez, president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, and other bishops from California, Hawaii and Nevada arrive to concelebrate Mass at the Basilica of St. Mary Major while making their "ad limina" visits in Rome Jan. 30, 2020. (CNS/Paul Haring)

The dominant fact of ecclesial life in the United States the past several years has been the resistance to Pope Francis among large sections of the faithful and even the bishops. The pandemic briefly brought Catholic leaders together, but by year's end, the opposition to Francis was as strong as ever.

Yet 2020 began with that great act designed to deepen communion with the Holy Father, the ad limina visits in which all the bishops go to Rome for meetings with the pope and with the different dicasteries that help the pope exercise his ministry. Various bishops said they enjoyed the frank conversations with the pope, with whom they met in small groups for a couple of hours, rather than the 10-minute, one-on-one sessions at which not much was accomplished during previous ad limina visits.

It didn't take. Some bishops used the visits to put words in the pope's mouth, saying he agreed with their decision to name abortion "our preeminent priority" in the election, even though the key distinction was whether or not the issue is "a" priority (with which we can all agree) or "the" priority, which is more problematic.

Some also went to Catholic News Agency anonymously to report that the pope badmouthed Jesuit Fr. James Martin, although two others, Archbishop John Wester and Bishop Steven Biegler went on the record to say the pope had done no such thing. I do not recall previous ad liminas involving these kiss-and-tells, do you?

By the time the visits were concluded in February, the coronavirus had begun to change the way the entire country went about its business and by March, the entire country went into a shutdown. I was pleasantly surprised that the bishops did not rush to the offices of the Becket Fund to complain that the government had ordered public Mass services suspended and prepare for another religious liberty battle.

By May, however, the common good took its first assault when the Minnesota bishops announced they would defy their governor's restrictions on worship. I will grant that not every governor or mayor implemented sensible regulations: Attendance caps that treated large churches the same as tiny ones made no sense. Still, comparing church worship to shopping made less sense and appealing to religious liberty misrepresented church teaching entirely.

Sadly, the religious liberty caucus at the bishops' conference is merely an arm of the culture warriors at the Knights of Columbus and the Federalist Society. As I have noted before — and it held true this year — they do not preach Christ and him crucified (cf. 1 Corinthians 2:2) but James Madison and him justified.

Washington Cardinal Wilton Gregory expresses thanks after employees at the Archdiocesan Pastoral Center in Hyattsville, Maryland, surprised him Dec. 3, 2020, with a banner and red balloons to welcome him home from the Nov. 28 consistory at the Vatican during which Pope Francis created 13 new cardinals. (CNS/Catholic Standard/Andrew Biraj)

One bright spot this year came at the Knights of Columbus' expense when Washington Archbishop Wilton Gregory criticized them in no uncertain terms for hosting President Donald Trump for a photo-op. The event was held at the Knights' St. John Paul II National Shrine in Washington the day after the president's henchmen had cleared peaceful protesters away from St. John's Church on Lafayette Square so that the president could pose for the cameras holding a Bible.

"I find it baffling and reprehensible that any Catholic facility would allow itself to be so egregiously misused and manipulated in a fashion that violates our religious principles, which call us to defend the rights of all people even those with whom we might disagree," Gregory said of the Knights' hosting the president. "Saint Pope John Paul II was an ardent defender of the rights and dignity of human beings. His legacy bears vivid witness to that truth. He certainly would not condone the use of tear gas and other deterrents to silence, scatter or intimidate them for a photo opportunity in front of a place of worship and peace."

Francis evidently approved of Gregory's stance, awarding him a red hat five months later.

I feared that some bishops would be even more aggressive and obnoxious during the election cycle than they were. Detroit Archbishop Allen Vigneron foolishly gave an opening prayer at an event for an anti-abortion group at which the group announced an endorsement of Trump. There were some regrettable tweets and unfortunate pastoral letters from other bishops. EWTN's Michael Warsaw covered himself in disgrace shilling for Trump's reelection but that was to be expected. Bishop Joseph Strickland of Tyler, Texas, always manages to put the "lie" in "outlier," endorsing a video made by a ranting Wisconsin priest who claimed no Catholic could vote for Joe Biden. Still, it could have been worse, much worse.

At the U.S. bishops' conference meeting after the election, it did become worse. The leadership of the bishops' conference overlooked its own bylaws to establish a task force on how to deal with the incoming Biden administration; Francis called to congratulate President-elect Biden.

It is clear that on most issues, Biden will be much closer to the mind of the church than was his predecessor. Yet, former Philadelphia Archbishop Charles Chaput became the public face of a campaign to deny Communion to the president-elect with a poorly reasoned essay at First Things. If you want to sum up the sad state of the U.S. hierarchy today consider this fact: Our president-elect, whom many bishops think is not a "real Catholic" and who should be denied communion, is more likely to favorably quote Francis than many bishops.

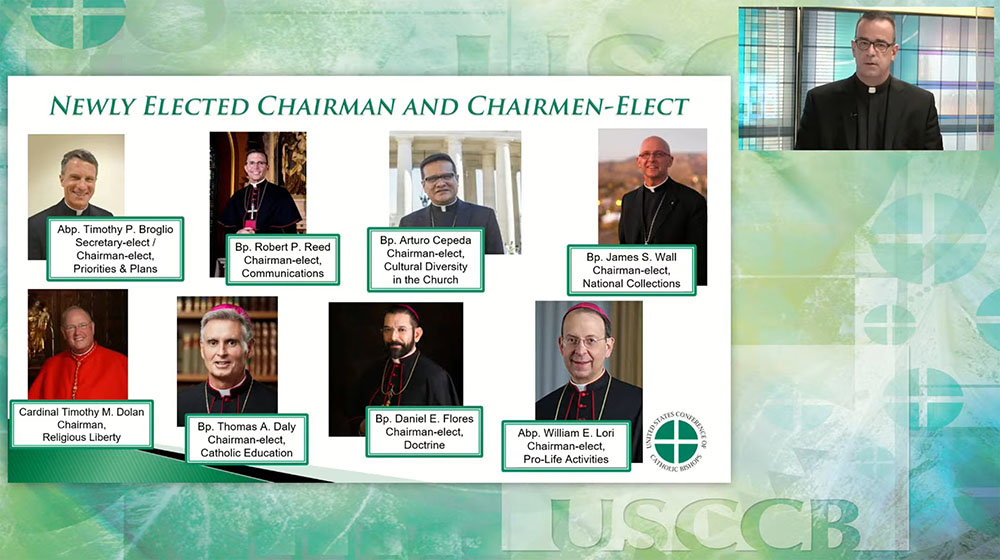

The U.S. bishops' conference meeting also featured elections for committee chairs, and the results confirmed the degree to which the conference will remain a Francis-free zone. The most illustrative contest pitted conservative darling Bishop Thomas Daly of Spokane, Washington, against Archbishop Gregory Hartmayer of Atlanta for the chairmanship of the Committee on Education. As one bishop told me before the vote, "That contest will show if there is room for a moderate in the conference." There isn't. Daly won 139 votes to 103.

It has become clear that conservatives organize and campaign for these committee chair elections and liberals note that there is not supposed to be any campaigning. Guess who will keep winning?

Msgr. J. Brian Bransfield, outgoing general secretary of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, announces the results of elections Nov. 16, 2020, for seven new chairmen-elect and one chairman of various committees. (CNS screenshot)

The resistance to Francis is only partially rooted in his social teaching. After all, the social teachings of Pope Benedict XVI and Pope John Paul II were quite critical of the spread-eagle capitalism embraced by the Republican Party so many U.S. bishops seek to bolster. No, the real source of the opposition lies in Francis' ecclesial vision, and that has been obvious since the promulgation of Amoris Laetitia in 2016.

Much of the early controversy surrounding Amoris Laetitia focused on the footnote opening the door to the reception of holy Communion by those who were divorced and civilly remarried. That point is still controversial to conservatives but their hostility is more broadly grounded.

Francis' teaching on the role of conscience in moral decision-making was consistent with the tradition, but conscience had not been highlighted by his immediate predecessors nor taught in any depth at most seminaries. Relatedly, Francis sees discernment and synodality as better capturing the ecclesiology of Vatican II, and for many bishops, that ecclesiological vision is disturbing.

Conscience, discernment and synodality are attributes of a church that behaves as if the Holy Spirit is still at work in the world, and at work in surprising ways. This is a thought the conservative opposition to the Holy Father cannot abide.

The problem is not that some bishops and lay Catholic leaders have discerned the situation of LGBT Catholics or divorced and remarried Catholics and reached different conclusions about how to minister to such people. No, the problem is that there are some who do not think there is anything to discern, that they have all the answers needed, that discernment suggests possible alternatives. Highly teleological, they believe that the natural law admits no exceptions, indeed that any suggestion of ambiguity undermines the law.

The stance is above all Kantian, quite different from the approach of, say, Aquinas who believed that natural law yielded principles that need to be applied with the virtue of prudence to concrete situations and that it is precisely the role of conscience to make that application.

Advertisement

There is no excusing Francis' critics, but I confess I am also disappointed at times in some of his episcopal allies. Just before Christmas, the Chicago Archdiocese announced a new solar array had been installed on the campus of the diocesan seminary at Mundelein. It has been six years since Francis published "Laudato Si', on Care for Our Common Home," and the vast physical plant of the Chicago Archdiocese has only one sustainable energy feature? Producing less than a megawatt of electricity? Chicago Cardinal Blase Cupich has been one of Francis' strongest defenders in this country, but why has he not demonstrated leadership converting the many buildings he owns — and the archdiocese is corporation sole — to sustainable energy? Why is he not leading by example?

Boston Cardinal Sean O'Malley is a member of the pope's kitchen cabinet, the Council of Cardinals. In his commitment to the poor throughout his life as a priest and bishop, no American cleric more closely resembles the Holy Father than O'Malley. But he is also the publisher of the Boston Pilot, which remains a hotbed of anti-Francis ideology. Regular columnists include John Paul II biographer George Weigel and Catholic University of America President John Garvey, neither of whom has distinguished himself with any pro-Francis advocacy. In May, Weigel published an attack on the Amazon synod in The Pilot — and O'Malley had been a synod father! I would have sacked The Pilot's editor that day.

Some of the new appointments this past year show that the winds of change are blowing even in the U.S. church: Archbishop Mitch Rozanski in St. Louis and Hartmayer in Atlanta are very promising choices. The verdict is still out on Archbishop Nelson Perez in Philadelphia and, crucially, Bishop Steven Raica of Birmingham, Alabama, ground zero for opposition to the pope, EWTN. The conference needs another 30 pro-Francis bishops and needs them soon.

In March, the Catholic Church will celebrate the eighth anniversary of the election of Francis. For too many U.S. Catholics, this pontificate remains a bit of bad weather they hope will pass. The Vatican nuncio, the president of the U.S. bishops' conference, and the pope's allies among the hierarchy need to look for new and creative ways to deepen the ecclesial communion between the church in this country and the Apostolic See.

Next week, we will look at what the new year may portend but I confess that, looking back at the year now coming to a close, it is hard to get past a deep-seated sense of ecclesial ennui.