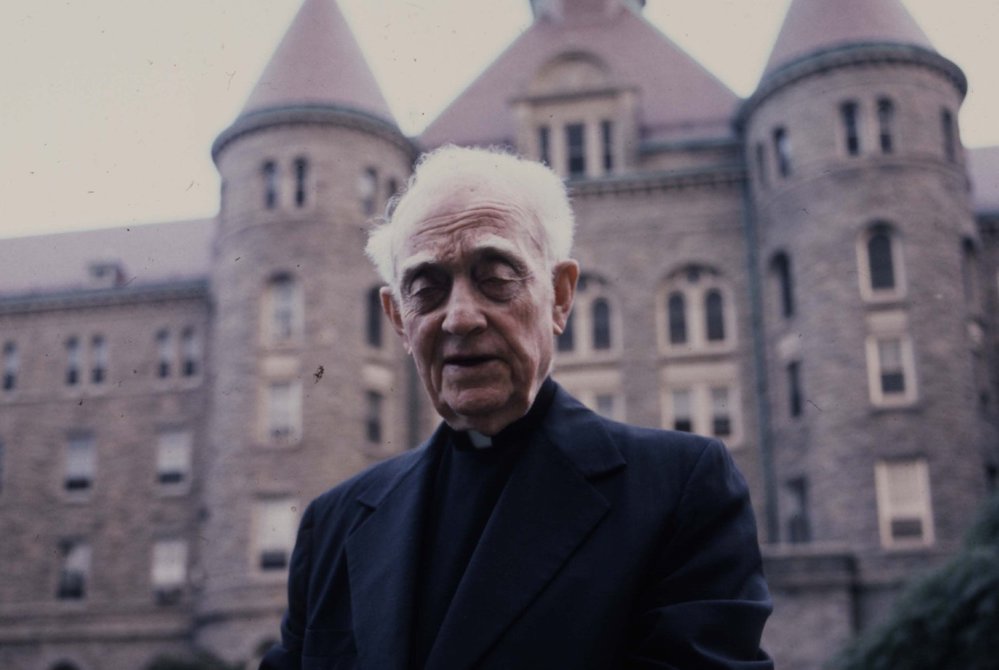

Msgr. John Tracy Ellis (1905-92), known as "dean of American church historians," was a professor of church history and theology who taught at the Catholic University of America 1938-64 and 1977-89. John Tracy Ellis: An American Catholic Reformer, a biography by the late Thomas Shelley, was published in June. (Courtesy of Catholic University of America, University Libraries, Special Collections)

Few things are as satisfying in the life of a Catholic journalist as to be on the receiving end of the kindness of scholars and clergy who help us in the media get to the bottom of something. There is, if you will, a fraternity of people who work with words the way others work with their hands. This fraternity is especially strong when the people involved are grouped around a shared love of someone or something. On top of all that, it allows me to say, with Blanche DuBois, that I've always relied on the kindness of strangers!

In March, the chairman of the board of directors of NCR, Jim Purcell, sent me an email asking if I would be interested in seeing a monograph he discovered. It was written by my great mentor Msgr. John Tracy Ellis. I said "Of course!" and Purcell put it in the mail. The essay ran to 20 pages, with an additional two pages of endnotes. It was not dated, but it identified Ellis as a professor at the University of San Francisco, so it was written before 1976 when he returned to Washington, D.C. but after the close of the Second Vatican Council in 1965.

The title "On the Selection of Bishops for the United States" did not indicate if this was a lecture or the draft of a magazine article. I asked Purcell if he knew to what purpose the monograph had been put, and he checked with a priest in San Francisco who instructed me to reach out to Fr. Tom Shelley, a priest of the New York Archdiocese, who is working on a biography of Ellis. I did so, and Shelley let me know that Ellis had published two articles on the subject, one for Commonweal and the other for The Critic. I took a photograph of the first page and sent it to Shelley. He replied that the monograph was identical to the opening of the article in the July, 1969 issue of The Critic.

The mystery of the mongraph's origin was solved. What of the essay's content?

Advertisement

First, the monsignor begins with the tale of Antonio Rosmini's 1847 book Concerning the Five Wounds of the Holy Church, which strongly criticized the pressure placed on the church through the role of secular governments in the selection of bishops, and that the Vatican placed the volume on the Index of Forbidden Books at the request of the Austrian government. Rosmini reminded his readers that for the first thousand years of the church's history, both laity and clergy had been involved in selecting their bishops.

By the end of Ellis' first few paragraph, you are reminded of his elegant writing style, straightforward but willing to take a slight detour for literary reasons or to introduce an analogy. For example, after detailing contemporary resistance to the idea of widening the consultation process in selecting bishops, he writes:

In that regard it should first be stated with absolute clarity that no right thinking Catholic, clerical or lay, entertains any disposition to wrest from the hands of the sovereign pontiff his centuries-old right to name in the final reckoning the successors of the apostles. It is rather that this movement, if movement it can be called, is only one more manifestation of the Zeitgeist of the 1960s in the Catholic community of the world and of the United States.

No one writes like that anymore, and it is a shame.

Ellis then traced the history of how bishops were selected over the years, starting with the patristic era and through the Middle Ages with its nepotism and, later, the politically devised solution of granting the right to nominate bishops to particular sovereigns. He comes to the founding of the American episcopate and records the well-known fact that, in a nod to local sensibilities, the Holy See allowed the clergy of the young United States to gather and select one of their own to be the first bishop. On May 18, 1789, the clergy gathered in the Chapel of the Sacred Heart at White Marsh, which can still be visited in Bowie, Maryland. They selected John Carroll, and by year's end, Rome had confirmed the selection. Over the next 40-odd years, until the Second Provincial Council in Baltimore in 1833, six methods for choosing bishops emerged in different situations.

Sacred Heart Church at Whitemarsh in Bowie, Maryland, built around 1741 (Library of Congress/Historic American Buildings Survey/Jack E. Boucher)

From 1833 until the meeting of the First Plenary Council of Baltimore in 1852, the metropolitan and each of his suffragans drew up a list of three names, a terna, for each vacant see, and the ternas were sent to both the metropolitan and the Propaganda Fide office in Rome, as the United States was still considered mission territory. The bishops included their reasons for the names given, but the ternas were only recommendations, and the final terna to be brought to the pope was drawn up by the cardinal members of Propaganda Fide.

Things remained in flux for several decades. At the Second Plenary Council of Baltimore, held in 1866, the apostolic delegate, Archbishop Martin Spalding, wanted legislation that would give a role to the consultors of a diocese in the drawing up of ternas, but no legislation was adopted on this point until the Third Plenary Council in 1884. Finally, diocesan consultors and irremovable rectors were given the right to draw up a terna for a vacancy in their diocese, which was then supplemented by a terna from the bishops of the province. In the case of a vacant metropolitan see, the other metropolitan archbishops would add a third terna of their own, drawn up at their now annual meetings.

Two other developments affected the selection of bishops in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The most significant was that in January 1893, Pope Leo XIII named an apostolic delegate to the United States, mostly to resolve conflicts between clergy and their bishops, but the delegate's influence in relating the situation on the ground to Rome gave him enormous influence in the process. Secondly, in 1859, the North American College opened in Rome.

Between 1884 and 1916, when the right of priests to draw up a terna was abrogated, 22% of the new bishops had received some or all of their training in Rome. From 1916 until 1966 when the National Conference of Catholic Bishops was formally commenced, 40% of new bishops had Roman training. Seventy percent of all cardinals had Roman training.

Ellis documented some post-conciliar efforts in other countries to increase the role of the clergy, religious and laity in the selection of episcopal candidates. He notes that the bishops in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, especially his beloved Cardinal James Gibbons, were more keen to better conform the church to the democratic tenor of the country. He notes the words of Bishop Richard Gilmour of Cleveland and Bishop John Moore of St. Augustine, Florida, in a memorandum to the Propaganda Fide cardinals in 1885:

Owing to the democratic form of government in the United States, the people must be taken into consideration, and their good will cultivated. Without their hearty and constant cooperation, neither Church nor Schools nor Institutions can exist or be created …

Ellis writes of the efforts of Bishop Ernest Primeau of Manchester, New Hampshire, to introduce greater consultation with his clergy in the selection of names he, in turn, shared with his brother bishops at their annual provincial meeting. But only a minority of the priests even bothered to respond to Primeau's request for names to be put forward for nomination as bishops. Ellis does not mince words in rendering his verdict, writing:

The Manchester experience should not, I think, be passed over without attention being drawn to the disappointment occasioned by the priests' failure to take their new responsibility seriously, for mutatis mutandi there is not a diocese in this country that has not undergone similar frustrations by reason of the priests' refusing to open their minds to new ideas and to manifest the courage to face up to the need for change in this revolutionary age. In all too many cases they have displayed a paranoid reaction which, even where it was strenuously opposed by some of their number, was strong enough to paralyze the general clerical body and nullify the talent that is latent in so many priests.

Ellis records other examples of attempts to include priests in the consultation process, even noting the rudeness of the apostolic delegate in failing to respond to a group of priests in Albany and a resulting editorial in NCR on the subject! (See "Washington double-talk," National Catholic Reporter, Vol. 5, No. 22.)

Ellis finishes his essay with some lovely quotes from John Henry Newman. I remember as if it was yesterday when he told our class that after the Lord Jesus and his mother, no person had had a greater influence on his life and ideas than Cardinal Newman. I remember sitting in that room thinking: How cultured must be the mind that can say such a thing, identifying with a person he had never met but whose writings had made such a profound impression

The Pontifical North American College on the Janiculum Hill overlooking St. Peter's Square in Rome (CNS/Cindy Wooden)

The two great churchmen were cut from the same cloth I came to realize. Brilliant, erudite, liberal in the best sense of the word.

I also recall the day when the monsignor spoke to a rally called to protest the removal of Fr. Charles Curran from the theology faculty at Catholic University. Monsignor, whose age required him to hold up his own eyebrows, made his way to the microphone and, looking at Fr. Curran, said something like: "Father, I disagree with you on every point of moral teaching on which you diverge from the teaching of the magisterium, but I strongly defend your right to teach your ideas at a modern Catholic university, free from ecclesiastical interference." Monsignor's sojourn in San Francisco had been occasioned by a similar interference.

I wonder if Ellis would still hold to the ideas he held then. So much has changed. Democracy has lost some of its luster in the age of Donald Trump and Matteo Salvini and Viktor Orbán. The polarization in the church was emerging when he wrote this article, but even when he died in 1992, the full extent of that polarization was not evident. It is a fool's errand to predict how someone who died almost 30 years ago would view the same issue today.

His knowledge of church history, however, would prevent him from becoming despondent about the situation of the church in 2021. The collapse of Christianity in revolutionary France was followed by the flowering of spirituality and then theology in that country throughout the 19th and into the 20th centuries. The long suppression of Catholicism in England was part of the cultural inheritance that produced Ellis' hero John Henry Newman as well as a host of other great Catholic thinkers and writers.

He would often quote the words of the Master to Nicodemus at John 3:8, to us, his students: "The wind blows where it wishes, and you hear its sound, but you do not know where it comes from or where it goes. So it is with everyone who is born of the Spirit."