Pete Buttigieg New Hampshire campaign memorabilia displayed at state party convention. (Wikimedia Commons, Marc Nozell)

The Great Hall of the Bretton Woods resort is very quiet on the late October mid-afternoon I arrive. Staff members are setting up bars for a reception in the Conservatory, a half-circle shaped room that looks out and up to the peak of Mount Washington. One woman sits at a table not far from a large grandfather clock. A gentleman reads his tablet next to the fieldstone fireplace. The leaf peepers left a week ago after the last of the autumn foliage fell. The snow, and with it the skiers, has not yet arrived.

The quietude is no impediment to my project. It is campaign season and this is New Hampshire. I do not want to talk to the visitors, but to the natives, so I make my way to the bar in Stickney's restaurant on the lower level. Bartenders always know what is going on.

"No, never," says Rachel, the barkeep at Stickney's when I ask her if customers are talking about the 2020 primary. "People talk about sports, not politics." Fittingly, ESPN is on the television against the wall. Rachel says she "should learn more" about the candidates, registers her disapproval of President Donald Trump, and says her brother is more plugged-in and she will talk to him before voting. A local comes into the bar and they talk about house renovations, not politics. Upstairs, at the bar in the "Princess Room," Matthew is tending bar. He also says that with customers he never discusses politics or religion. I refrain from explaining I am a columnist who writes only about those topics. Both bartenders are aware of the fact that their place of employment has historical significance but neither is too clear what that significance is.

Seventy-five years ago, 44 nations sent delegates, mostly finance ministers, to the Bretton Woods resort where they negotiated the architecture of the postwar economy. They understood the need for multilateral solutions. They tied the dollar to gold and all other currencies to the dollar. They created the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. They understood that capital flow had to be controlled and prosperity widely shared if the world was to avoid the kind of economic turmoil of the 1920s, which led to the rise of fascism.

Causality is a difficult thing to assign, but the Bretton Woods system set the framework for 30 years of economic growth with minimal income inequality, and with no recessions. In 1971, Richard Nixon delivered a blow to Bretton Woods when he repudiated the gold standard. Then Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan delivered the fatal blow with their embrace of laissez-faire economics.

The IMF and World Bank have adapted to the changed political climate, making them complicit in some of the negative aspects of laissez-faire.

Advertisement

"In part what resonates with many workers around Trump's America first policies is that we've seen the 'multilateralism' of the World Bank, the IMF and the World Trade Organization or the 'Bretton Woods' institutions, promote a financial system that enriches a few and forsakes most of us," Eric LeCompte, executive director of JubileeUSA, told me in an interview.

Those finance ministers in 1944 did not know it, but their work has also set the terms of the 2020 election. All Democrats support multilateralism. President Trump pursues an "America First" policy that ends up being "America Alone." He does not support multilateralism even among his own staff: It is all against all, dog-eat-dog, all the time in Trump's orbit. Democrats support multilateralism, in both economic and foreign policy, and they promise to rebuild our alliances.

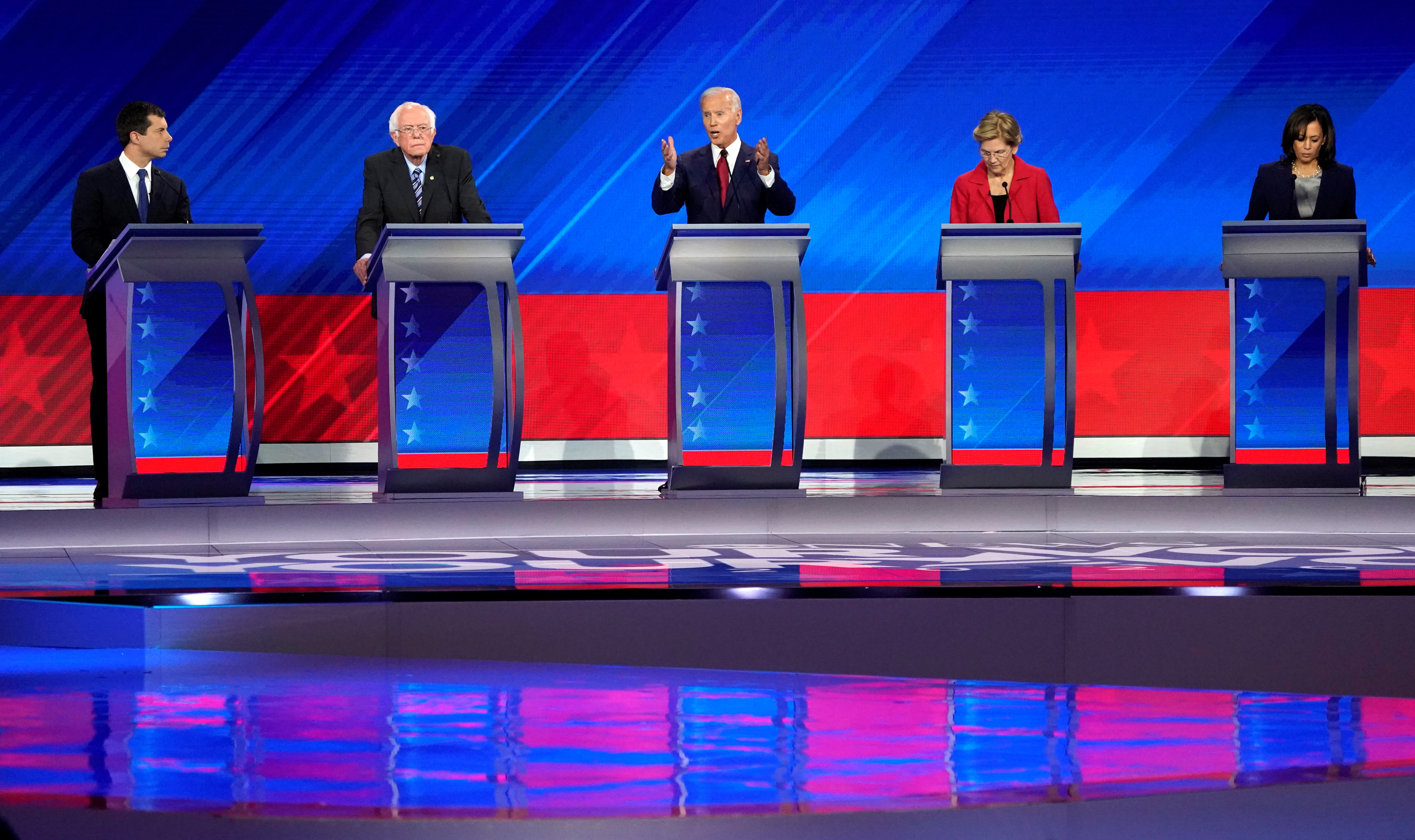

Bretton Woods also defines the key divide among the Democratic candidates. On one side, the so-called moderates — former Vice President Joe Biden, Mayor Pete Buttigieg, and Sen. Amy Klobuchar — are content trying to amend the post-Bretton Woods, libertarian economy, a nibble here, a tweak there. On the other side, Sens. Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren want to pursue the second objective Bretton Woods achieved, controlling capital, and recognize the structural changes needed to achieve that.

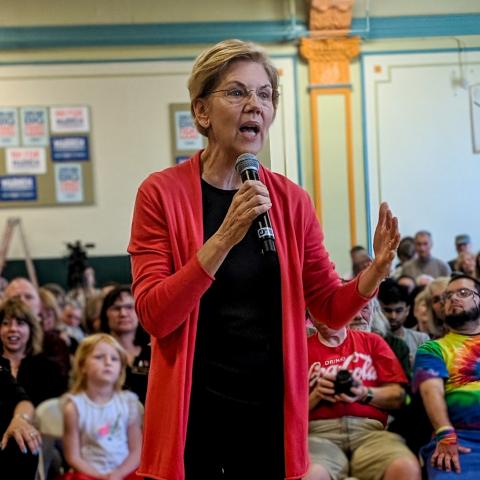

A Warren rally

Newport is the kind of sleepy town that in another state might never receive a visit from a presidential candidate: Decidedly working class, like many old mill towns, it has seen better days. It boasts a population of 6,507, there is a village green with a Protestant church on it, and the only industry in town is the Ruger gun manufacturing plant.

This is New Hampshire, however, so even though the primary is more than three months away, and Newport seems pretty far off the beaten path, the line to attend Sen. Elizabeth Warren's town hall snakes down the sidewalk more than an hour before the event begins.

Elizabeth Warren campaigns in Nashua, New Hampshire in May 2019 (Wikimedia Commons, Marc Nozell)

Volunteers and staff are welcoming the people in line. In order to get in, you need to text the campaign with a special code, and then enter your name and zip code, creating a voter list for the campaign.

"Everyone I know says, 'whoever gets the nomination, I'll support,' " a woman named Linda tells me. She, like others gathered here, would give only a first name. Others nod in agreement. "We have to get Trump out of there," adds Lynn, who is also standing in line.

Linda explains that she was first inclined to support Biden. "I worked on his first Senate campaign in 1972, when I was a student at the University of Delaware," she tells me. "I got his Christmas cards. I love Joe." But, she doesn't think his heart is in the race. "He feels obligated," she says.

"I've met Liz a couple of times," Linda tells me. Her daughter attended Harvard Law. "She's sincere and she's very, very bright. We need someone honest and brilliant. I don't know if all her plans will come to fruition, or should."

Lynn says, "I want to know more about 'Medicare for All.' I like the idea, but I'm not sure how she wants to go about it. I want to hear more." Lisa tells me she was impressed with Warren's tackling the banks. "That in itself shows she is a strong person with good values."

Most of the people in line refer to Warren as "Liz," to Sanders as "Bernie," and to Biden as "Joe." It is New Hampshire.

Inside, staff are bringing in extra chairs as the Newport Opera House fills. The room could pass for any Grange Hall except for the large, oak balcony and the carved "boxes" next to the stage, all festooned with red, white and blue bunting. An enormous American flag, a stool and a glass of water are the only things on stage. A campaign organizer for the county asks everyone to greet the people sitting near them, just like in church on Sunday morning, and thanks everyone for coming to hear "the best candidate that money can't buy." State Rep. Brian Sullivan, who is a teacher, takes the microphone and, by way of introduction states that Warren "will replace Betsy DeVos," and the room erupts in applause. I wonder how many people in America know the name of the Secretary of Education but this is a roomful of plug-in voters. That "plugged-in" quality makes me feel slightly better about New Hampshire's outsized role in selecting a nominee, but it is still weird to be in a room where virtually everyone is white.

Warren bounds onto the stage, waving her now famous, high-energy wave and jumps into her stump speech. She is funnier than I expected and the audience eats it up. After about a half hour of intertwining her biography with her policy proposals, repeatedly returning to her central theme — government is rigged to help the rich and the powerful and only big structural change can fix that — she takes questions from the audience. The last of the three questioners does not really pose a question but reads her rambling "wish list" of 20 items. Warren picks up on two of them in her answer, thanks everyone for coming, and promises to stay and take a selfie with anyone who wants one. Most of the people form a line. Forty minutes after the end of her speech, Warren is still taking selfies.

Former U.S. Vice President Joe Biden speaks during the 2020 Democratic presidential debate in Houston Sept. 12, 2019. Other candidates pictured are Mayor Pete Buttigieg of South Bend, Ind., and Sens. Bernie Sanders, D-Vt., Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., and Kamala Harris, D-Calif. (CNS photo/Reuters /Mike Blake)

Outside of the early primary states — Iowa, Nevada, New Hampshire and South Carolina — no presidential candidate would have time to visit a small town like Newport. Few voters in the other 46 states would find it so easy to meet all the presidential wannabes. New Hampshire, though, is no longer typical of the U.S. For starters, it is very white, 93 percent, according to the last census. The morning after Warren's event, I am surprised to find 33 people, plus the priest, gathered for an 8 a.m. weekday Mass in St. Patrick's church. I can't remember the last time I went to Mass and not seen a single Latino in the congregation — until that morning.

A world away

New London is 15 miles and half a world away from Newport. There are a couple of tony restaurants and the Blue Loon bakery along its main street. The houses coming into town are well kept and the cars in the driveways are upscale, not the trucks and old sedans down the road in Newport. The town is dominated by the campus of Colby-Sawyer College, a small liberal arts college where tuition and fees came to $39,450 for the 2016-2017 academic year and all the brick, Georgian buildings have WASPy names like Danforth Hall and the Ware Student Center.

The morning I arrive, the line to get into the Ware Center for Mayor Pete Buttigieg's event on empowering women is quickly filling with students. The older folk have already snagged their place and the first person I see is Linda, the woman I met the night before at Warren's town hall. "I like that Mayor Pete is young and he represents the future," she tells me. "I hear he changes [his positions] because of the polls, but I am not sure. You have to have integrity."

Nan is a retired Catholic schoolteacher who says she is pretty close to committing to Buttigieg. "He has integrity, he is super smart, intellectual," she explains. "He is a bridge to Warren and Sanders, with a slight edge of moderation that might be helpful." Nan does not like Sen. Kamala Harris whom she calls "too egotistical," but she likes Warren and also Klobuchar.

Matt has made up his mind. "Mayor Pete is the most moderate of all the candidates," he tells me. "He is able to maintain a compassionate presence on stage and doesn't indulge vitriolic or polarizing language." He offers an analysis of the Electoral College, and the significance of Buttigieg being from the Midwest.

Matt was the first person at either campaign event who said it was "too early to say" if he would support any Democrat who wins the nomination. "I do favor more free market policies," he explains. "I am not a fan of Donald Trump, but I don't know. It is too early to say."

Inside, the hall fills quickly. Daytime political events typically feature an older crowd, but here it is mixed with young people from campus. There are few middle-aged people outside the press section. It strikes me that the older folk, more than the young students, like the fact Mayor Pete is so young: I suspect they wish he was their kid. The young people are attracted to his being gay. Among the dozen or so people I spoke to, none cite a policy position of the mayor, except a student who praises Buttigieg's support for reproductive rights, a position that does not distinguish him from any others in the field. The adjective "moderate" is invoked by the older members of the audience.

The mayor knows that his only path to the nomination is in the moderate lane. In explaining his tax policy, he tells the audience, "I'm not even talking about going back to the 1960s' levels of taxation," before quickly adding, as if he knows he is trafficking in a neo-liberal talking point, "although I would point out the economy did quite well back then." He is the epitome of sweet reasonableness. Economic policy is not the only thing separating Buttigieg from Warren. She uses the word "fight" in every other sentence. Mayor Pete always sounds like the McKinsey consultant he once was.

Today, Democrats largely agree on a host of issues, but the divide on economic policy is deep and pervasive.

Like Warren the previous night, Buttigieg weaves his personal biography into his speech: When he speaks about how everyone feels excluded in some way, he relates his coming out story. He says he wondered how coming out would affect his political career but that the voters of South Bend reelected him with 80 percent of the vote. That is true: Mayor Pete secured 8,515 votes in 2015 to 2,074 for Kelly Jones, his Republican opponent. His tale of voter tolerance for his being gay is also a tale of voter apathy: Only 14 percent of voters turned out in 2015. He leaves that part out.

It is clear Buttigieg is connecting with white, upper middle class voters in New Hampshire, many of whom collect a "Pete 2020" lawn sign as they leave. The fact he is gay is clearly a plus here. New Hampshire is socially tolerant: In 2018, Chris Pappas won election to Congress in the state's 1st congressional district, becoming the first openly gay person to represent the Granite State in Congress. You can't help but wonder: If Buttigieg were straight, would his campaign have gained traction as it has?

One of the things that distinguishes Buttigieg is his willingness to speak openly about his faith, although he does not work it into his talk on this day. When I ask Linda what she thinks of Buttigieg's use of religious language, she frowns and invokes the memory of "religious wars." She says she wants to "keep religion out of politics."

Religious impact?

In New Hampshire, at least, Linda will get her wish, according to Neil Levesque, director of the Institute for Politics at St. Anselm's University. "No," he answers when I ask if religion will affect the primary. "Of course, there is always something." He notes a new megachurch has sprung up in Concord, the state capital. And, in the band of Boston exurbs that line the state's southern border, churches have been built to accommodate the growth. Levesque explains that those border towns are the heart of the "GOP belt" these days. In Virginia, population growth in the D.C. suburbs has turned the state blue, but in New Hampshire, the Boston exurbs keep the state purple.

In 1960, Richard Nixon beat John Kennedy in New Hampshire by almost 7 points. Apart from Lyndon Johnson's landslide in 1964 the state was reliably Republican until Bill Clinton narrowly won the state in 1992. Democrats have taken the state's three electoral votes in six of the last seven elections. Levesque attributes the shift to the wars under the two Bush presidencies. Rural New Hampshire is now blue.

Levesque says that cultural Catholics, those who were born into the church and identify as Catholic when asked but who rarely attend Mass, are not in any single political tribe. Observant Catholics are overwhelmingly Republican and few exhibit what Levesque calls "the full peacock," embracing all the church's teachings. "If you asked me to find you a Catholic who attends Mass weekly, and comes out saying he is pro-union, anti-abortion, anti-death penalty and pro-immigrant, you won't find it." At a recent town hall for Biden, no one asked a question about his religion.

Pope Pius XI (Wikimedia Commons)

I tell Levesque about going to Mass in Newport and there being no Latinos. He says that there has been a small Latino presence in Nashua for some time, and a growing one in Manchester. Nashua's St. Louis de Gonzague parish, still spelled in French, has a Spanish Mass every weekend in a neighborhood that now boasts some Mexican restaurants and shops. If there is a Spanish language Mass in Manchester, I could not find it.

What I did find in Manchester was a town that is newly hip and with lots of problems. The textile mills that stretch for over a mile along the Merrimack River converted to shoe-making in the 1930s, but that industry left in the 70s and the state's largest city fell on hard times. Now the mills house some swanky restaurants, a dozen tech companies and some high end condos. Along Elm Street, the city's main drag, I walk past several enticing restaurants and craft brewpubs before settling on Republic, a farm-to-table café. The blackboard near the door lists the source of their produce, beef, pork and lamb, and the menu is very post-modern. The customers are all businesspeople, smartly dressed. On the bar there is a copy of the New York Times and the Boston Globe. I ask the barkeep if they also put out the Union-Leader, Manchester's conservative local paper. They don't.

Driving out of town, an older woman bangs on my car window asking for money. Manchester is now home to many of the victims of the opioid epidemic. There are homeless people everywhere.

Social teaching

Religion may not be a big player in the Democratic primary, but it brought Carli Stevenson back to her home state to work as communications director for the Bernie Sanders campaign. She and her wife run the Catholic Worker House in Indianapolis but she has twice returned to New Hampshire to work for Sanders.

Carli is helping to organize some 50 staff and volunteers for a citywide canvas of Concord. They are busy signing up, grabbing some Dunkin' Donuts coffee, being briefed on the basics of going door-to-door. "This work is hard," Carli says. "If you didn't have something really deep driving you, it's even harder."

"I would say that I think of all the candidates out there, Bernie most closely embodies Catholic social teaching, and if you talk about preferential option for the poor, he is your guy," Carli says enthusiastically. "The essence of Catholic social teaching is the sense that Jesus came and hung out with the lepers and the people at the margins. That's the real thing." She starts to get choked up. "To be fully in my faith is to go to the margins." She talks about her work at the Catholic Worker where they provide housing to people in transition, including an older woman recently who was waiting for a bed at an Alzheimer's clinic and some trans young people who were in unsafe situations. Carli is no Christmas and Easter Catholic.

Four years ago, Sanders famously interrupted his campaign to fly to the Vatican to participate in a conference at the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences. He briefly met the pope. "It was very exciting," Carli recalls. "I think Bernie has said on multiple occasions that he admires Pope Francis. For me, it was exciting to see my candidate go and visit and be in this place where we have a pope who, for the first time in a long time, speaks to someone like me." She pauses as if sorting through the memories of that long time. She likes Pope Francis because "he doesn't focus on legalisms and policing and fixating on people's private lives, but on caring for the poor."

Moral stances

Catholic social teaching is rich and varied in its assessment of modern political societies, but at its heart are two essential moral stances. First, that government exists to assist society, its power should be limited, and the politics it requires is a human good. Second, unbridled capitalism is unworthy of the human person and destructive of human society. In his great encyclical Quadragesimo Anno, Pope Pius XI wrote:

Just as the unity of human society cannot be founded on an opposition of classes, so also the right ordering of economic life cannot be left to a free competition of forces. For from this source, as from a poisoned spring, have originated and spread all the errors of individualist economic teaching ... free competition, while justified and certainly useful provided it is kept within certain limits, clearly cannot direct economic life — a truth which the outcome of the application in practice of the tenets of this evil individualistic spirit has more than sufficiently demonstrated. Therefore, it is most necessary that economic life be again subjected to and governed by a true and effective directing principle.

Pius's language, like the Bretton Woods accord, is a voice from the past. But that bit about a "poisoned spring" still rings true. Four years ago, Donald Trump promised an economic populist agenda, but then filled his administration with guys from Goldman Sachs. Twelve years ago, Barack Obama promised hope and change, but he always hesitated before tackling the kind of deep economic change that would have brought the laissez-faire regime begun by Thatcher and Reagan to an end. Today, Democrats largely agree on a host of issues, but the divide on economic policy is deep and pervasive. The voters I met in New Hampshire seem cognizant of the policy implications embedded in the choice they have to make, even while they mostly like all the candidates and are as driven by questions of character as policy.

I am typically suspicious of theories about American exceptionalism. Yet, driving back from the White Mountains, I could not suppress the thought: Only in America could a Jewish guy from Brooklyn via Vermont and a Methodist lady from Oklahoma via Massachusetts be advocating economic policies that fit neatly under the banner of Catholic social teaching.

Michael Sean Winters covers the nexus of religion and politics for NCR.]

Editor's note: Don't miss out on Michael Sean Winters' latest. Sign up and we'll let you know when he publishes new Distinctly Catholic columns.