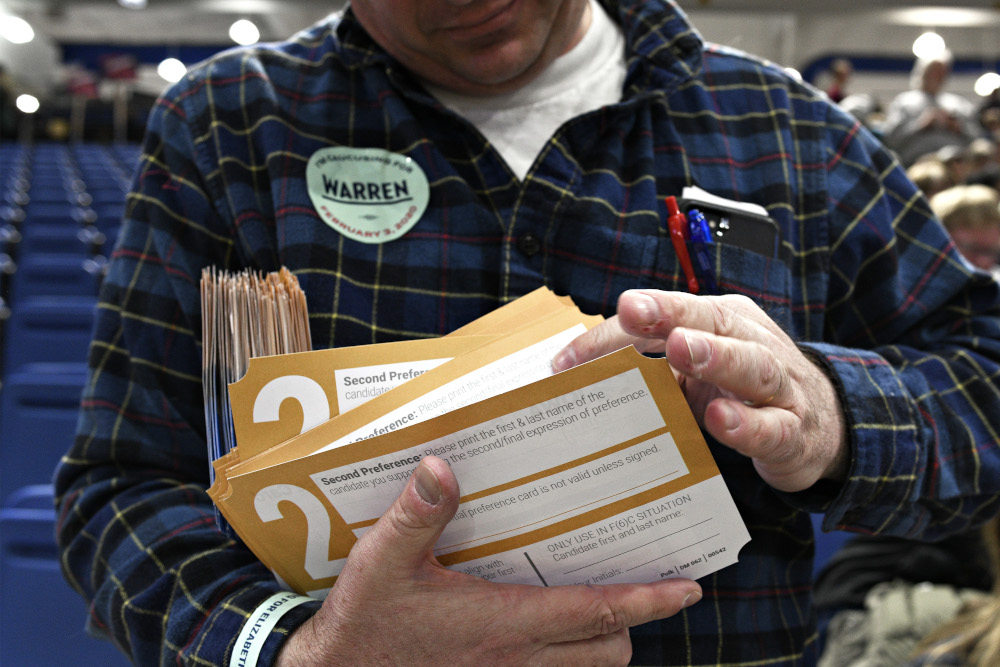

A caucus volunteer thumbs through the Presidential Preference Cards after the first round of caucusing in the Knapp Center at Drake University in Des Moines. (Newscom/Polaris/Jeff Topping)

What a strange night Monday was. And a strange Tuesday morning! The pundits and talking heads —increasingly accustomed to the world of data and demographics, in which analysis is reduced to mathematical equations, drawn to the idea that the movements of history are inexorable, the result of impersonal, sociological forces — they did not know how to cope with the fact that the Iowa Democratic Party screwed up. Massively. Human frailty intervened. From Heaven, St. Augustine was laughing at the mortals.

The inability of the Iowa Democrats to deliver the results of the Monday caucuses in real time meant, in effect, that no one won the caucuses. The key is to be giving a victory speech on live television before midnight. In 2012, on election night, Mitt Romney was declared the victor in Iowa, but a fortnight later, it became clear that Rick Santorum had actually won. It was too late. Romney had already gone on to win New Hampshire and he ran the table.

The most immediate winner Monday night was Neil Levesque, director of the Institute for Politics at St. Anselm's College in Manchester, New Hampshire. He is hosting the next debate on Friday night. Iowa clarified almost nothing except that it is time to do away with caucuses. The good people of the state of New Hampshire now get to set the terms of the Democratic nominating process.

Technically, according to the 62% of results finally released by the state party Tuesday at 5 p.m., Eastern, former South Bend, Indiana Mayor Pete Buttigieg secured the highest percentage of delegates at 26.9%, but Sen. Bernie Sanders led in the final popular vote total with 28,220. Sanders had the second highest percentage of delegates with 25.1% and Buttigieg came in second in the final popular vote, with 27,030 votes. Sen. Elizabeth Warren was third in both categories with 18.3% of the delegates and 22,254 in the popular vote. Former Vice President Joe Biden staggered into fourth with 15.6% of the delegates and 12,176 in the popular vote.

The entrance polls — given the nature of the caucuses, the networks take entrance polls, rather than exit polls — indicated that 25% of caucus-goers described themselves as "very liberal," 33% as "moderate or conservative" and 43% as "somewhat liberal." Sanders did best among the "very liberal" cohort, and Biden and Buttigieg tied among the "moderate/conservative." No surprise there. Buttigieg did best among the "somewhat liberal" voters, which means that issues matter less than we pundits tend to think: Buttigieg is not at all liberal. The exit polls also indicated that 17-29 years old voters constituted 23% of the voters, up from 19% in 2016, and those young voters broke heavily for Sanders. Buttigieg did surprisingly well among them as well.

The entrance polls indicated the degree to which sexism remains a problem. Men were only 42% of voters Monday night, and Sanders did best among them with 25% of the vote, followed by Buttigieg with 19% and Biden with 18%. Warren was a distant fourth with 13%.

One of the problems with polling in Iowa is that the structure of the caucus — requiring voters to show up at the same time and at the same place — demands a really effective field operation. And no poll is able to detect the effectiveness of a campaigns ground game in advance. All last year, staff and volunteers were reaching out to voters, identifying those who support their candidate, staying in touch to keep that support, and making sure the voter shows up at the caucus. The ground game is always the least glamorous but often the most important part of any campaign and this is especially true here.

The Iowa caucuses have a two-tiered process. After hearing from representatives of the campaigns, the voters move to different sections of the room to caucus for their preferred candidate. Each candidate must obtain 15% of the voters at each site to be termed "viable." In the second round, those who supported a candidate who did not make the threshold, who have been termed "not viable" can caucus with one of the viable candidates. Consequently, it is really important to be the second choice of candidates like Andrew Yang or Tom Steyer, candidates unlikely to be deemed viable. And, this was the first time the popular vote totals of both rounds were released to the public.

I cannot think of a better test of a candidate's ability to unite the Democratic Party than to outpace other leaders in the ability to attract voters who originally supported someone else.

Why does this two-tiered process matter? I cannot think of a better test of a candidate's ability to unite the Democratic Party than to outpace other leaders in the ability to attract voters who originally supported someone else. And, uniting the party is the sine que non for beating President Donald Trump in November. The person who gained the most on the final ballot was Buttigieg: His initial total was 23,666 votes, and he gained 3,364. Warren gained the second most between the two ballots, adding 1,406 votes. Sanders added 1,132 to his initial total. Unfortunately, who can trust the final numbers after the debacle Monday night? And the numbers released Tuesday at 5 p.m. are not final, they only represent 62% of the vote.

Uniting the party won't be easy for any of the candidates. CNN had a reporter at a precinct in Dubuque where Warren did not even cross the viability threshold. Dubuque is an overwhelmingly Catholic county: more than 56% of the population are Catholics. I could not help recalling that when Warren announced her "faith advisory team" it included 14 liberal Protestants, 1 Reform Jew, and 1 Sensei. No Catholics. I need hardly point out that 56% of the population of Dubuque County do not follow a Sensei. Warren needs to shake up her team: They need to take a nap, that is, become less woke, a lot less woke.

Biden's weak showing was a bit of a surprise, especially because so many voters indicated that they thought he stood a good chance against Trump, and beating Trump was their highest priority. Voters are ill-advised to play the pundit, and they should vote for the candidate they think will make a good president. Perhaps, in the end, strategic voting is too mechanistic to actually motivate voters.

It is far too soon to know if Buttigieg can use his strong showing Monday to catapult his campaign forward when it moves to South Carolina, where a majority of the primary voters will be black. Buttigieg has struggled to connect with black voters.

Sanders got more votes in 2016 than he did Monday night, but 2016 was a two-person race, so that is an unfair comparison. He did very well among young voters and very liberal voters, and they turned out in greater numbers than they did four years ago. Is it enough? He bombed among moderates and it is difficult to see how he will improve his standing with them. Like Buttigieg, he has also struggled with African American voters. The real problem with Monday's results? He has based his ability to defeat the president on the idea that he can attract new voters to the polls. First-time voters did support Sanders more than the others, but overall turnout was about the same as four years ago and did not even come close to the turnout in 2008.

Advertisement

That year, then-Sen. Barack Obama's surprise victory launched his campaign. It was not just that he upset Hillary Clinton. Nor was it that there had been a record turnout. Obama proved he could win in an overwhelmingly white state. Before Iowa, black voters were divided between Obama and Clinton. After Iowa, black voters shifted overwhelmingly to Obama. He also minimized the effect of his disappointing loss in New Hampshire the following week by delivering the best speech of his life, his "Yes, we can" speech that was shortly thereafter set to music.

A good friend called Monday night and said he was nervous that none of the Democratic candidates stood much of a chance in November against Trump. I am not so sure. At this point in the race in 1992, Bill Clinton's draft dodging had just hit the news, and the nation was about to meet Gennifer Flowers, who alleged a longterm affair with the candidate and had tapes that more or less backed up her story. He did not contest Iowa, because native son Sen. Tom Harkin was in the race. He came in second in New Hampshire, announced he was the "comeback kid" and went on to win. Campaigns strengthen some candidates and destroy others. No one knows how many banana peels await any of the candidates. The candidate who can defeat Trump is not the person who avoids all those peels, but the candidate who slips on one of them but then gets up and lives to fight another day.

This year, the Iowa caucus came on the eve of the State of the Union address and two nights before the final impeachment vote. The results will not dominate the news cycle as they did in 2008. More importantly, the results were clustered close enough to each other that it is hard to say anyone took a huge leap towards the nomination. Buttigieg is better placed to own the moderate lane than he was the night before Iowa. Sanders is still formidable and is best placed to own the progressive lane. Warren was not knocked out, nor was Biden.

One thing we know for sure? The first question posed in Friday night's debate should be: Why do you think you are best positioned to unite the Democratic Party?

As the race heads to New Hampshire, we can conclude that Iowa echoed the apostle, St. Paul: Now, we see in a glass, darkly.

[Michael Sean Winters covers the nexus of religion and politics for NCR.]

Editor's note: Don't miss out on Michael Sean Winters' latest. Sign up and we'll let you know when he publishes new Distinctly Catholic columns.