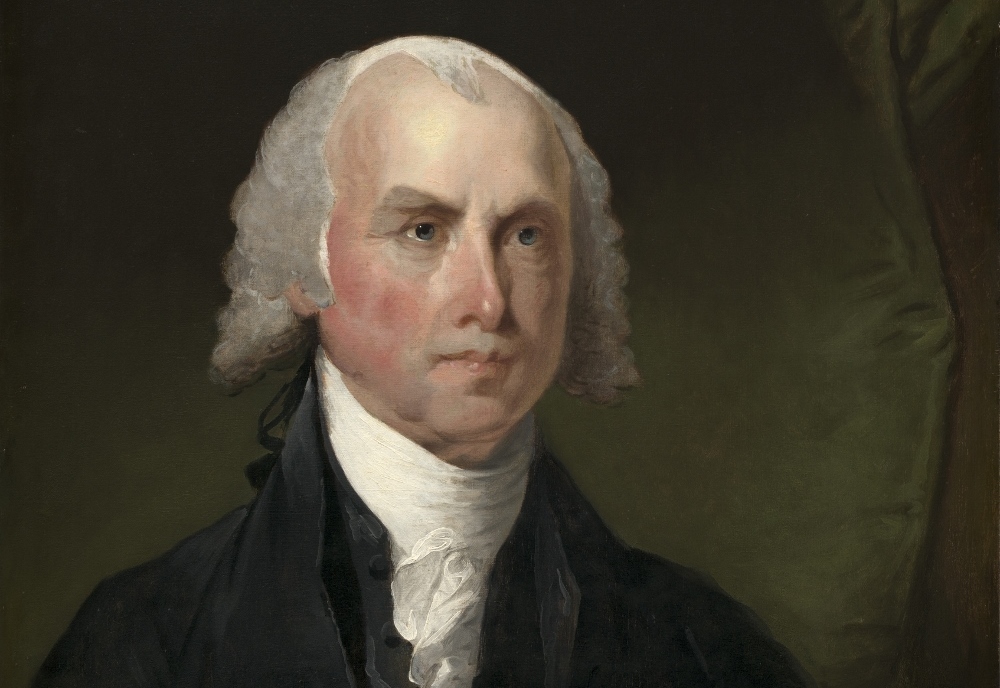

Detail from a portrait of James Madison, circa 1821, by Gilbert Stuart (National Gallery of Art)

Part 2 of 2. Read Part 1 here: Kavanaugh hearings prompt a closer look at originalism

Wednesday, I began this article on originalism, looking at how it has developed over the years since Robert Bork, Antonin Scalia and others first articulated the idea, focusing specifically on an article by Lee Strang that had been commended to me in a Mirror of Justice column by Kevin Walsh.

I noted several problems with this intellectual approach. The greatest problem, it seems to me, is that Strang's would-be marriage of virtue ethics and originalism leaves originalism behind altogether. He claims virtue ethics will make originalism "more descriptively accurate" in four ways:

(1) originalism will be more hospitable to and paint in a better light common practices; (2) originalism will be able to embrace the widespread and attractive conception of judging as a craft; (3) originalism will be able to emphasize the fact that constitutional interpretation is a human practice; and (4) originalism will better fit the Framers' and Ratifiers' plan of constitutional government which embraced their virtue-infused assumptions.

The entire project rests on No. 4 being plausible, but he has to rip the word "virtue" out of its 18th-century context and claim it has the same meaning as that suggested by the teleological, Thomistic philosophy of John Finnis and Germain Grisez. The result is tenuous at best. Strang's historical argument, as distinguished from his legal one, is crude: James Madison spoke of "virtue" and so does Strang. So, they must be on the same page? No?

Thomistic virtue, in the public sphere, manifests itself as part of an organic social order. Thomas Aquinas does not embrace the contractualism of John Locke that motivated Madison. Ironically, Strang cites the Madison quote that demonstrates the extent of the divide between the worldview of the Framers and that of Thomas and Aristotle: "If men were angels, no government would be necessary."

Thomists, though mindful of the Fall, do not believe human nature as depraved as the Framers did, influenced as the latter were by Locke and, standing always over his shoulder, by Thomas Hobbes. There is no warrant in Catholic social teaching for the conception of individual autonomy, nor the suspicion of government, that haunted the Framers. There is nothing in Catholic, or Aristotelian, thought that wiggles self-interest into a virtue as the Framers sought to do.

Yes, both discuss virtue. What generation of humankind does not? But there is nothing in the historical record that suggests the conception of virtue that animates 20th-century Catholic moral theologians was in the mind of Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and certainly not the anti-Catholic bigot John Jay.

In short, Strang's essay seems unaware of the danger of placing our own modern concerns and values upon the writings and thoughts of earlier times. Historians wrestle with these kinds of intellectual danger all the time. In the March 2018 New England Quarterly, the entire issue of which focused on the 50th anniversary of Bernard Bailyn's Ideological Origins of the American Revolution, Bailyn himself commented:

There are dangers in creating this kind of constructed conversation or debate, and I had been aware of them. One could gather together similar sounding expressions to form an apparently consistent grouping, or tradition, or party line that in fact never existed. That is, one could construct a narrative, an intellectual story, that was in fact an authorial construct, an account of one's own devising.

I fear that this is exactly the idiosyncratic flaw that dogs Strang's essay. Actually, as a friend smarter than me pointed out, Bailyn's quote is not exactly on point, because he is addressing the care one must exercise in bringing disparate historical documents, from the same 18th century, into conversation with one another. How much more care must be exercised to bring 18th-century documents into conversation with our modern concerns? Strang does not demonstrate such carefulness.

Virtue ethics might yield the results in constitutional interpretation that Strang wants. It may prove the salvation of the Republic, for all I know. But to label it originalism is a stretch.

Strang would not put it this way but I shall: Originalism as understood today in law reviews, then, is not as originalist as it pretended to be in the 1970s and as it still purports to be in the public square. Those in the conservative commentariat who repeat the bumper-sticker slogans from the days of Bork about originalism when speaking to the cameras, while admitting all manner of innovation when needed in law review articles, need to be more candid. If originalism is what Strang says it is, it has as much in common with the original intent of the Framers as Justice Harry Blackmun's penumbras.

As noted Wednesday, Walsh also commended an article he had co-written with Notre Dame Law Professor Jeffrey Pojanowski titled "Enduring Originalism" and published at the Georgetown Law Journal. Many of my difficulties with this essay are similar to those I have with Strang, so let me just cite a couple of examples.

Advertisement

Right up front, the authors state their objective: "This Article explains how the classical natural law tradition of legal thought, which is also the framers' tradition, supplies a solid jurisprudential foundation for constitutional originalism in our law today." But there is a faulty, or at least unproven, premise in that statement, namely, that the "classical natural law tradition of legal thought" was also the "framers' tradition."

Again, I ask the simple question: Which Framers? And at which point in their careers? The early Madison of the 1785 Memorial and Remonstrance against a bill providing state funding for religious education, or the more radical late Madison of the detached memoranda, circa 1817 in which he argued against permitting religious corporations to own too much property:

But besides the danger of a direct mixture of Religion & civil Government, there is an evil which ought to be guarded agst in the indefinite accumulation of property from the capacity of holding it in perpetuity by ecclesiastical corporations. The power of all corporations, ought to be limited in this respect. The growing wealth acquired by them never fails to be a source of abuses. A warning on this subject is emphatically given in the example of the various Charitable establishments in G.B. the management of which has been lately scrutinized. The excessive wealth of ecclesiastical Corporations and the misuse of it in many Countries of Europe has long been a topic of complaint. In some of them the Church has amassed half perhaps the property of the nation. When the reformation took place, an event promoted if not caused, by that disordered state of things, how enormous were the treasures of religious societies, and how gross the corruptions engendered by them; so enormous & so gross as to produce in the Cabinets & Councils of the Protestant states a disregard, of all the pleas of the interested party drawn from the sanctions of the law, and the sacredness of property held in religious trust. The history of England during the period of the reformation offers a sufficient illustration for the present purpose.

Is this the position of, say, the Becket Fund today? Is the intent of this founder, and not just any founder but Madison himself, binding on today's originalists? Will Judge Brett Kavanaugh, when confirmed, attack the church's right to own property?

Later in the piece, Walsh and Pojanowski write, "Constitutional originalism justified on these grounds captures what is true and valuable about the positive turn while providing the normative foundation that makes originalism worth defending." I must say the phrase "normative foundation" has a decidedly curious, and Catholic, ring to it. It is not the kind of thing one would expect to come out of the mouth of some of our founders, certainly not those who increasingly fell under the sway of Enlightenment ideals.

Nor does this quote sound like something that Madison would approve: "What is decisive is the point of view of the morally reasonable person toward the social fact of our stipulated positive-law Constitution — not social facts about what today's legal officials happen to believe about interpretive method. And the practically reasonable person's attitude toward our Constitution, we argue, should be originalist." That sure sounds like a tautology to me.

Happy the man who has enough time on his hands to get involved in these kind of intramural academic debates. Lucky the woman who can mix and match ideological impressions and try and fashion something new in the realm of scholarship. But, in a democracy, what we say about law and government must, in the end, be accessible to the demos, to the people. And while I listened to much but not all of the confirmation hearings the past few days, I did not hear Kavanaugh or his Republican senatorial champions citing Aquinas or Aristotle. They did, repeatedly, invoke Scalia. They did, repeatedly, commend Kavanaugh as an originalist.

The legal theory may have developed nuances since Bork and Scalia first articulated it, but the measure of that nuance is the same measure by which the theory ceases to be originalist. Walsh was correct in saying I was unfamiliar with developments in originalist legal theory. And I am correct in asserting that if originalism is what Strang, Walsh and Pojanowski say it is, it is no longer originalism. And that means Kavanaugh and his defenders are not only amateurish in their historical analysis, they are hypocrites as well.

[Michael Sean Winters covers the nexus of religion and politics for NCR.]

Editor's note: Don't miss out on Michael Sean Winters' latest: Sign up to receive free newsletters and we'll notify you when he publishes new Distinctly Catholic columns.