A man in Laredo, Texas, stacks relief boxes at the South Texas Food Bank March 20 during the coronavirus outbreak. (CNS/Reuters/Veronica G. Cardenas)

It will take more than COVID-19 to kill the ideologies of our day that distort our political landscape and distend our organs of governance beyond recognition. Or am I the only person tired of the genre "What the coronavirus means to me" and how the examples from that genre, regardless of ideological persuasion, usually result in some version of the claim: In this thoroughly unprecedented moment, what I have believed all along is emphatically confirmed. Claims to prescience are as contagious as the virus!

I hope that some brilliant researcher will find a cure for the coronavirus. Today, let's try slaying some of the ideological stupidities the crisis has brought into focus.

Last week, a Senate vote on the stimulus bill was held up at the last moment as four Republican senators — Lindsey Graham, Ben Sasse, Rick Scott and Tim Scott — voiced objections to the provision that would give an extra $600 per week to all those filing unemployment claims. Graham said the proposal "pays you more not to work than if you were working," creating a disincentive to work, a longtime GOP bugaboo.

To quit one's job, in the middle of a pandemic and economic recession, in order to access higher unemployment benefits, would be a decision so stupid, it is hard to see how any government policy could affect it one way or the other. But Graham's own stupidity was shining through here: If you quit you job, you are not eligible for unemployment benefits. They only kick in if you are fired or laid off.

The problem, however, is deeper. Republicans, and the economists who love them, have been essentially lying to the American people about the nature of economic incentives for a long time. Real people are certainly motivated by the prospect of making more money, but it is not the only motivation they have.

Work brings existential dignity as well as a paycheck. Very few people I know envy anyone else who is on the dole. Since becoming a writer, I make about half what I made running a restaurant, and I loved my work then just as I love my work now, but my reasons for changing had to do with aging and other considerations, not primarily with a paycheck.

You see this political manipulation of an economic idea in other ways too. Republicans always justify tax cuts for the wealthy on the grounds that it incentivizes investment. A higher marginal tax rate means an investor has less of an incentive to invest than a lower rate.

Advertisement

But that equation compares the wrong choices an investor faces. Say you are invited to invest in a company and your investment stands to earn you $1 million. Is your motivation lessened appreciably if you will be taxed, say, 40% on your return versus 35%, a difference of $50,000? The real comparison is between the $1 million you stand to make, minus whatever the tax rate is, with the various other things you can do with your money.

Political ideologues of the left are out in force also. Andrew Yang is only too happy to draw comparisons between his "freedom dividend" and the direct payment to individuals included in the new stimulus law.

"So there are some differences, but the fundamentals are identical in terms of putting cash directly into our citizens' hands so that we can solve our own problems, stay healthier and, in this case, feed our families," he told NPR's Michel Martin.

If anything is blindingly obvious about this pandemic, it is that we cannot "solve our own problems." Libertarianism's aggressive hostility to solidarity may be downplayed by the undoubtedly decent Yang, but it still yields only a very impoverished understanding of solidarity.

Catholic social teaching demands more: an understanding that work confers dignity, not just a paycheck, and that social bonds cannot be reduced to contractual and rights-based concepts. Catholic teaching instructs us that one can ameliorate the harshness of our Hobbesian conflation of economic laws with natural ones by means of proposals like Yang's, but our Christology demands a rejection, not just an amelioration of the ill effects, of our laissez-faire, Thatcherite-Reaganite Weltanschauung.

Pope Francis, citing his predecessor St. Pope John Paul II's encyclical Novo Millennio Ineunte, reminds us in Gaudete et Exsultate, "The text of Matthew 25:35-36 is 'not a simple invitation to charity: it is a page of Christology which sheds a ray of light on the mystery of Christ.' " Our anti-libertarian stance is no mere ethical conclusion: To organize civil society around human autonomy is to create a new golden calf. The evidence is too obvious to require demonstration.

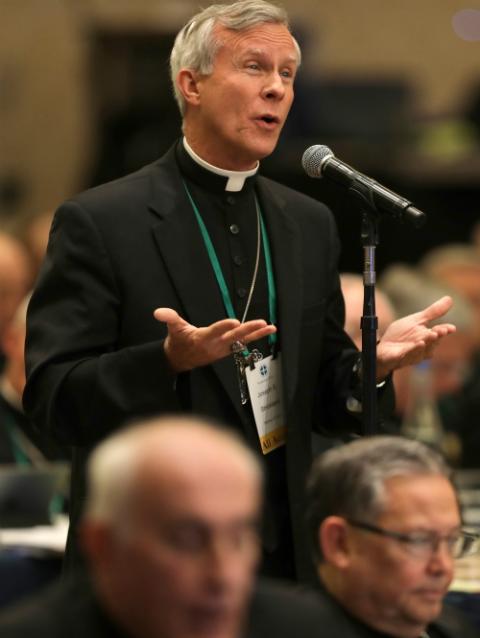

Joseph Strickland of Tyler, Texas, speaks during the fall general assembly of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops in Baltimore Nov. 11, 2019. (CNS/Bob Roller)

Sadly, some Catholic leaders have also been swept into ideological stultification. As noted yesterday, Bishop Joseph Strickland of Tyler, Texas, went on EWTN's "The World Over" with Raymond Arroyo and explained that subsidiarity is "my new word for all of this," fretting about "this mega-church which controls everything" and "that's not what Christ gave us."

Having taken a giant step toward Congregationalist ecclesiology, he also declined to sign a statement issued by his brother Texas bishops on scarce health care resources. In a post at the diocesan website, he again invoked subsidiarity: "The social ordering principle of subsidiarity must be applied. In short, a 'one size fits all' approach does not fully recognize the need to attend to the needs of particular people." Huh?

Strickland appears to be operating under a misunderstanding of the principle of subsidiarity, common among Catholics who frequent the Napa Institute, the Busch School of Business and Economics and other libertarian outfits. Subsidiarity commends decision-making at the lowest level of social organization possible but at the highest level necessary. That is to say, it is a two-way street. In a public health emergency, local decisions cannot be made outside the context of the whole or they will be futile. The virus does not recognize local boundaries. What is more, in our federal system, only the national government has the resources to address a pandemic.

Whatever the bishop meant about the church being a big organization that controls everything, who knows? If he is done playing Christian Science founder Mary Baker Eddy, maybe we should let him play John Winthrop and go start a Puritan colony somewhere. Somewhere other than New England, please God.

Perhaps it should not surprise us that, faced with an unprecedented and enormously challenging situation, people should reach for what they know and cling to their ideology as a child clings to his blankie during a storm. But we Christians have been given a different example. "When I was a child, I spoke like a child, I thought like a child, I reasoned like a child," the apostle Paul tells us. "When I became a man, I gave up childish ways."

Crises create fissures, wash away well-worn paths, overturn established ways of doing things. They create openings through which both wonderful new things emerge and from which new evils also rise. It is to these we shall attend on Friday.

[Michael Sean Winters covers the nexus of religion and politics for NCR.]

Editor's note: Don't miss out on Michael Sean Winters' latest. Sign up and we'll let you know when he publishes new Distinctly Catholic columns.