(Wikimedia Commons/Andreas Praefcke)

In the novel Brideshead Revisited, the devout Cordelia is telling agnostic Charles about the day they closed the chapel at Brideshead Castle: "The priest came in ... and took out the altar stone and put it in his bag; then he burned the wads of wool with the holy oil on them and threw the ash outside; he emptied the holy water stoup and blew out the lamp in the sanctuary and left the tabernacle open and empty, as though from now on it was always to be Good Friday. I suppose none of this makes any sense to you, Charles, poor agnostic. I stayed there till he was gone, and then, suddenly, there wasn't any chapel there any more, just an oddly decorated room."

As we enter into the sacred triduum, into the contemplation of the passion and resurrection of the Lord, we are invited to enter into those salvific events that constitute the very ground from which our faith springs, events that we believe are ongoing in the life of the church. If there is no institution of the Eucharist, no death upon the cross, no empty tomb, then there is no Catholic faith. Without this faith, our spiritual and moral lives would, like the chapel at Brideshead, become mere oddly decorated rooms.

What keeps us from the wonderment at the events of these three days that so obviously characterized the early followers of Jesus? What prevents us from the depth of conversion they had?

In our time, I do not believe that anything about Holy Thursday constitutes a large hurdle to faith. The idea that the Lord Jesus wanted to share a communal meal with his friends before the trauma that was to come is completely understandable. All of us in this age, as in every age, have experienced the brutal emotional toll of betrayal that Jesus experienced that night at the hands of first Judas and later Peter.

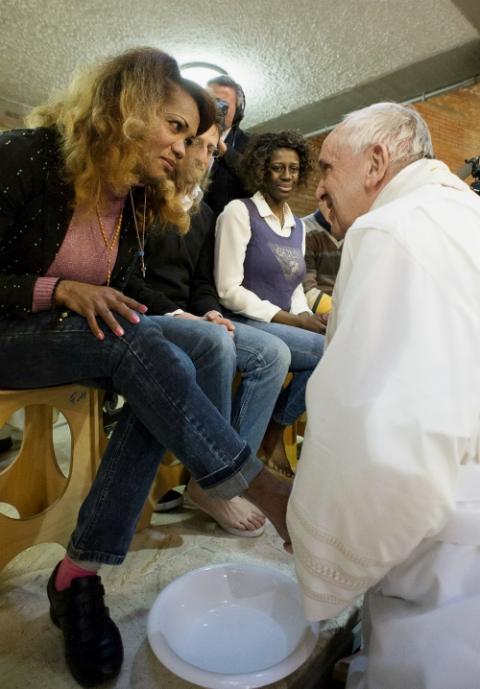

Pope Francis washes the foot of an inmate during the Holy Thursday Mass in 2015 at Rebibbia prison in Rome. (CNS/L'Osservatore Romano via Reuters)

We Catholics know how important the institution of the Eucharist and the priesthood are to our faith, and how the two are linked. Perhaps most importantly, the Mandatum rite reminds us in this second gilded age, when material wealth is confused with moral worth and we are taught — and taught young — to envy those with plenty, that to follow Jesus means to take off our cloak and kneel before our fellows and wash their feet, to become a servant.

Surely, the central reason the people in the pews love Pope Francis so deeply is that his disdain for the material trappings of his office and the evident joy he takes from being with the poor and the marginalized put us in mind of Jesus washing the feet of his disciples. I suspect, too, that all the ridiculous complaints coming from some disgruntled fat cats at the Papal Foundation are rooted in this quality of our Holy Father that the rest of us so admire. Both in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and now in Rome, he takes joy among the poor, not the rich, and the rich are accustomed to being feted and stroked and complimented.

Eastertide is also a thing I think modern men and women have little difficulty understanding. There may be misunderstanding around the edges of the central fact that the Lord is risen to new life. People may think that, like Lazarus, he takes up again his old life, when in fact it is as a new creation that Jesus emerges from the tomb.

Or they may believe in a false dualism between spirit and body that reduces the Resurrection to a spiritual reality, denying the bodily resurrection of Jesus or at least reducing it to a metaphor, even though we do not experience our bodies as metaphors. But the central idea that this good man was divine and somehow broke the chains of death, and that by clinging to him, we too might experience eternal life — this is not the stumbling block to our faith.

Advertisement

No, it is Good Friday that poses the problem. What is it about Good Friday that does not resonate in our culture? I think the problem is that we forget that Jesus had it coming. We talk about how he was the spotless, immaculate victim, and so he was. We are moved by the story of Dismas, the good thief, and we sing a beautiful Taizé chant to his words to the Lord, "Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom." We look to blame others for this death, most famously the Jews but sometimes the Romans, or at least Pilate.

No. Jesus got what he deserved. He challenged the moral structures and Temple worship of his day, and he paid the price. And the Temple was the center of Jewish life in a way no Catholic church, not even St. Peter's at the Vatican, is.

Look at how our nation reacted when the temple of our civilization — the World Trade Centers — were felled. We brought war to two nations. Should we be surprised that Caiaphas and the other priests demanded the life of the one who breezily spoke about destroying the Temple?

Jesus had violated the Sabbath repeatedly, self-righteously claiming he was restoring the right relationship between God and Man — I almost wrote that he had relativized God's law to Man — and the real religious leaders of his day insisted he had no authority to do so, that he had, in fact, profaned the religion they shared.

On the cross, he was exposed as the blasphemer, the charlatan that he was. No wonder the apostles fled. All their hopes were crushed under the weight of that cross.

On Sunday, we will sing with the universal church, across the continents and across the centuries, the great Alleluia as we confess that God's verdict, revealed in the empty tomb, was different from man's verdict. But, in this triduum, let us not rush on to the end of the story. Let's remember the day Christ died, the hours he hung upon the cross, and, like the apostles, see in that cross an invitation to despair.

Holiness, true holiness, does not consist in right living or moral probity. It is the ability to resist despair when the devil tempts us to believe God did not conquer sin and death on that first Good Friday. Let us, like the first apostles, sit with that despair so that we can, like them, experience the Resurrection as the literally earth- and cosmos-shattering event that it was, something so great, it saves a wretch like me.

[Michael Sean Winters covers the nexus of religion and politics for NCR.]

Editor's note: Don't miss out on Michael Sean Winters' latest: Sign up to receive free newsletters, and we'll notify you when he publishes new Distinctly Catholic columns.