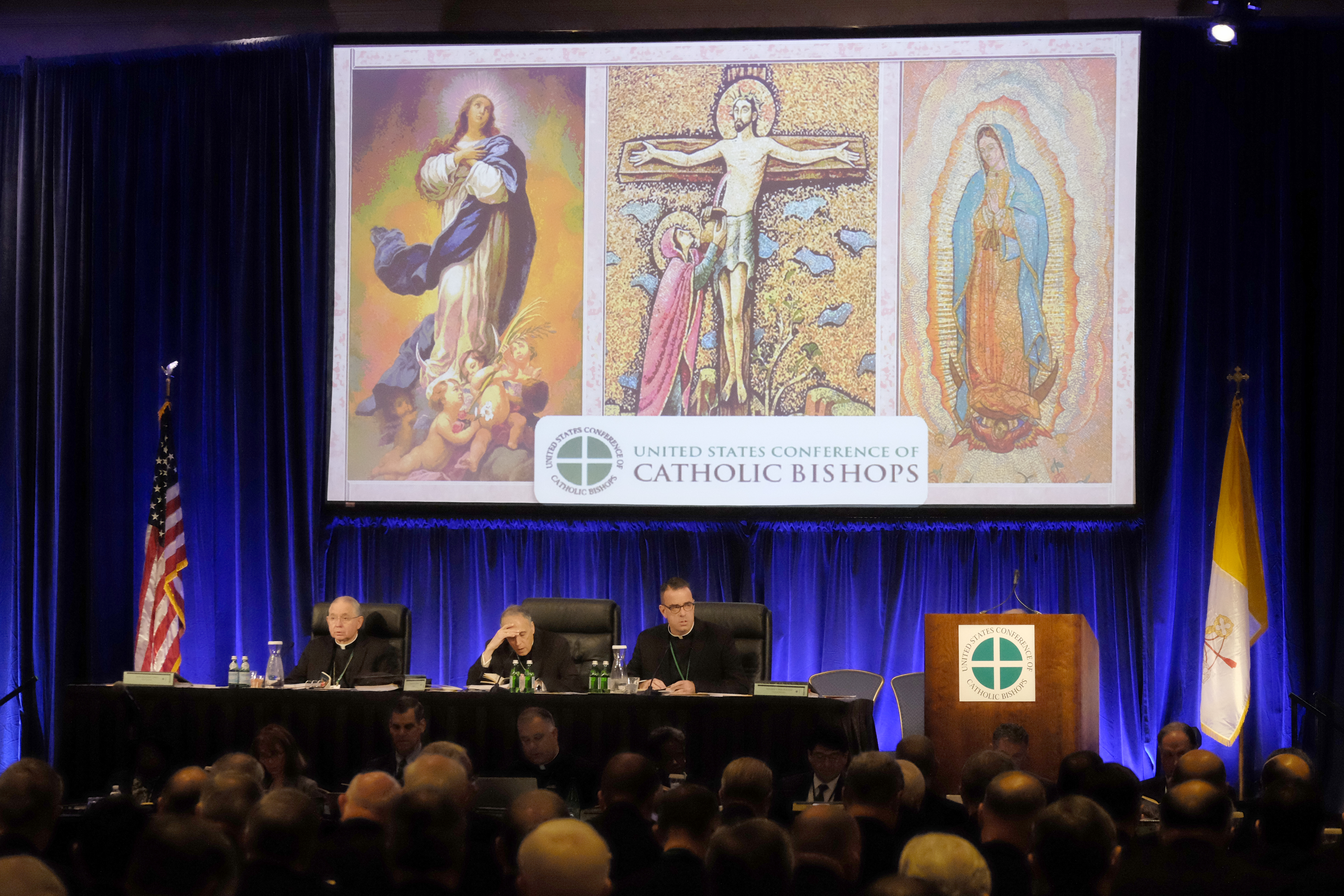

Cardinal Daniel N. DiNardo of Galveston-Houston, center, leads the opening prayer Nov. 13 during the fall general assembly of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops in Baltimore. Also pictured are Archbishop Jose H. Gomez of Los Angeles, vice president of the USCCB, and Msgr. J. Brian Bransfield, general secretary. (CNS photo/Tennessee Register/Rick Musacchio)

Was the Vatican wrong to insist that the U.S. bishops' conference not vote to enact proposals the conference leadership had devised to confront the clergy sex abuse crisis?

Most media commentaries offered a resounding "yes" to that question, the Vatican was wrong. In announcing the Vatican's decision, conference President Cardinal Daniel DiNardo admitted he was disappointed by the news. The two abuse survivors who addressed the bishops' conference expressed "deep disappointment" to NCR's Heidi Schlumpf.

The New York Times reported that no one really knew why the Vatican had taken the action it did. An editorial here at NCR floated different possible reasons for the Vatican action, and also noted that once the U.S. bishops discussed the proposals, "the bishops were hardly of one mind about them." And, I pointed out within hours of the announcement that the bishops' conference's proposals were manifestly inadequate.

I think it is obvious that Pope Francis "gets" the evil of sex abuse: His decision to ask for the resignation of the entire episcopate of Chile signifies that. Not since Napoleon's Concordat with Pope Pius VII in 1801 had an entire episcopate been sacked. We also know that the pope understands the crisis is one of clericalism and hierarchic malpractice: Pope Benedict was significantly better on sex abuse than Pope John Paul II, but only Francis was willing to demand the resignation of bishops who had been negligent in confronting abuse. Bishop Robert Finn is no longer the bishop of Kansas City-St. Joseph, and Archbishop John Nienstedt is no longer the archbishop of St. Paul and Minneapolis.

But, I suspect the pope does not understand the media culture in which the U.S. church operates. In this regard, I suspect he is like many U.S. bishops. As Robert Mickens convincingly argued in La Croix International, the U.S. bishops do not control their own communications with the people in the pews. That task has been ceded to a rightwing media empire that includes EWTN, the National Catholic Register and the Catholic News Agency, with help from First Things. Those bishops who have not realized this are largely those who are fine with it, which is really scary.

And, in most dioceses, if there is a newspaper on the kitchen table it is not the diocesan newspaper, but a secular newspaper, one that probably no longer even has a dedicated religion reporter. For the average Catholic, who doesn't subscribe to either NCR, who watches ESPN not EWTN, the bishops need the secular media to communicate with those Catholics.

I also wonder if the pope grasps how differently the American mind, and especially the American religious mind, works from that found in Catholic cultures. Pragmatism and an idolatrous belief in the power of logic run through every synapse of the American psyche. In the weeks after Pearl Harbor, Winston Churchill came to the United States for consultations with President Franklin Roosevelt. They held long meetings with their staffs, both political and military. In his war memoirs, Churchill writes:

At Washington intense activity reigned. During these days of continuous contact and discussion, I gathered that the President with his staff and his advisers were preparing an important proposal for me. In the military as in the commercial and production spheres the American mind runs naturally to broad, sweeping, logical conclusions on the largest scale. It is on these that they build their practical thought and action. They feel that once the foundation has been planned on true and comprehensive lines all other stages will follow naturally and almost inevitably. The British mind does not work quite in this way. We do not think that logic and clear-cut principles are necessarily the sole keys to what ought to be done in swiftly changing and indefinable situations. In war particularly we assign a larger importance to opportunism and improvisation, seeking rather to live and conquer in accordance with the unfolding event than to aspire to dominate it often by fundamental decisions. There is room for much argument about both views. The difference is one of emphasis, but it is deep-seated.

Churchill, of course, had been reflecting on the cultural differences of Americans from Britons all of his life: His mother was an American. The pope, who must monitor the church in the entire world, can be forgiven for not having achieved the level of insight about the peculiarities of U.S. culture that Churchill did.

Advertisement

In the religious sphere, the differences are even starker than in the military-political. I would love to watch the 1971 movie "The Homecoming" with Pope Francis. What would he make of the scene in which Patricia Neal states that, poor though they are, they will not accept charity in her home. Where in the Gospels would one find anything even remotely justifying what was and is a standard religious posture rooted so obviously in pride? The fixation of the U.S. church with the pelvic sins is not a fixation one finds in Italy or Spain or Latin America: In those Catholic cultures, Catholic identity is marked by other characteristics than sexual abstemiousness. The litigiousness of American society is obnoxious, seminal and abnormal, and it, too, has affected American religious culture.

Perhaps Cardinal DiNardo, who was in Rome for the entire month of October, should have explained the proposals to the pope with a view towards helping him understand the ways his legalistic and managerial proposals might shape the culture of the church in beneficial ways. Perhaps. I get the feeling that DiNardo and the pope do not see eye-to-eye on very much and after watching the debacle in Baltimore two weeks ago, no one, including the pope, could express much confidence in DiNardo's leadership.

I remain convinced that the pope was justified in squashing the vote. The proposals, in the final analysis, did little to address the clerical culture the bishops sustain. Still, I wish Rome would get into the habit of explaining its decisions more fully. Silence has its spiritual utility, to be sure, and this pope seems determined to reorient all of us away from the cultural norms of modernity and back to the essential spiritual norms of our faith. The bishops got into this mess in no small part because they listened to their lawyers, and listening to their communications' experts will not get them out of it. They must do the spiritual work the pope wants them to do. But, pastorally, the Holy Father needs to see how his decision demoralized many faithful Catholics. In so doing, he has raised the stakes for the February meeting of the presidents of all the world's bishops' conferences. That meeting must be successful in ways even we poor pragmatic, logical, litigious Americans can grasp.

[Michael Sean Winters covers the nexus of religion and politics for NCR.]