One of the greatest benefits of analog photography is that it encourages a new way of seeing the world. (Unsplash/Raimond Klavins)

What a lot of people may not know about me is that before I became a Franciscan friar, long before I was ordained a priest or became a theology professor, I was a professional photographer. In college, I studied both theology and journalism, and I worked as a freelance photojournalist for years covering sports, breaking news and feature assignments for a host of newspapers, magazines and wire services. And I loved it.

During the first couple years that I was in initial formation as a Franciscan, I still shot some assignments for a few editorial clients, while also photographing special occasions for ministries in my Franciscan province. I even led a photography class at one of our ministry sites in New York and ran a summer workshop on photography and spirituality in Boston.

However, once my studies in theology and ministry began, and certainly after being ordained, my life became busy with the work of sacramental ministry, teaching, researching and writing. With only a few exceptions (the occasional portrait shoot for my siblings' wedding engagements or a sporting event here and there), photography began to recede as a major part of my life.

Like millions of others, I found myself snapping images on a smartphone without much consideration, quickly capturing and then forgetting about fleeting moments and scenes of life. Meanwhile, my camera equipment sat boxed up in storage in friary basements.

And then the pandemic hit.

I initially found myself without the same demanding schedule of meetings, deadlines and travel I had accommodated over the years. It wasn't quite a retreat, since there was little about the pandemic that was spiritually, emotionally or physically renewing. But it was a different pace of life that allowed for lots of reflection and discernment, even in the midst of some horrific circumstances.

It was then that I found myself drawn back to this aspect of my life that had remained dormant for nearly two decades. I began by dusting off some digital gear, most of which is, by today's standards, archaic and worth practically nothing. But everything still worked, and I started making pictures again.

Advertisement

With walking around my neighborhood being one of the few things I could safely do during the pandemic, I started taking a camera with me to capture what I might see. My skills were certainly rusty. Photography is always part science and part art, so both sides of the brain required time to get back into gear.

And then something very unexpected happened. Thanks to the Internet, I stumbled upon a thriving community of analog photographers — those who were not shooting digital cameras, but using decades-old cameras to shoot 35mm, medium or large-format film.

What was shocking to me about this community is how it was led by young adults, most of whom had only known the digital world of smart phones and social media, of 4K video and YouTube "creators." These Millennials and Gen-Zers were un-ironically falling in love with an analog technology that had all but gone extinct. It was both surprising and, as I came to experience, deeply inspiring.

Unlike many of these young adults who were discovering film for the first time and almost single-handedly revitalizing the film-photography industry, I started out with film in the 1990s and for years even shot professionally with film. The early years of professional digital photography were rough with prohibitively expensive pricing for gear that rendered substandard image quality. I didn't start regularly shooting with a digital camera until 2003.

The reports of film photography's impending death were swift shortly thereafter. In 2004, Kodak announced it was ceasing production of film cameras. Two years later, Nikon announced it, too, would stop making most of its film cameras. Other manufacturers followed suit. At the same time, many film companies like Kodak, Fujifilm and Ilford suffered from rapidly declining sales and, in 2008, Polaroid announced it would stop producing its famed instant film.

It's no wonder then that I — like many others — was surprised to see this resurgence in film photography. Watching a new generation discover the analog experience that I not only took for granted, but was for the first half of my life the only option I had, induced some nostalgia but also excitement. Over the last few months I began shooting some film again, rediscovering a few drawbacks and appreciating the many blessings.

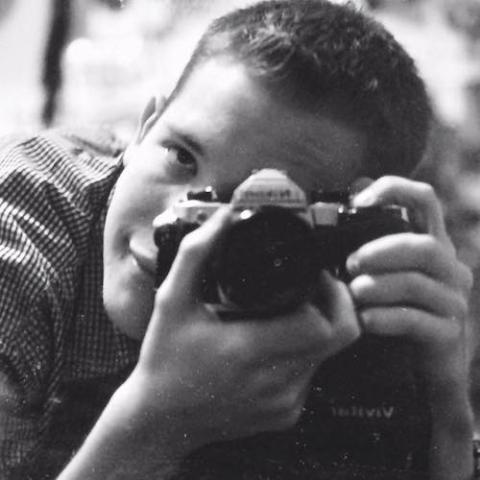

A self-portrait of Daniel P. Horan from around 1999 (Daniel P. Horan)

In my opinion, the only major drawback is cost. Film, while increasing in popularity these days, is still not always easy to get ahold of, and, therefore, the cost is higher due to low demand. You also have to get the film processed and scanned or printed, which you can do yourself, but setting up a darkroom and buying the chemicals and equipment is also quite expensive. So when you think about the total cost-per-image on film (around 40 cents each), it can add up.

And yet, the cost-per-image and slow processing is also one of film's greatest blessings: It forces you to think about every image you compose and take. It requires reflection, slowing down and deliberating about whether you want to use one of the limited number of frames you have on this roll of film for this particular shot.

You also don't have the luxury of instant feedback. There are no digital previews on the back of a film camera, and there is no way to share your images immediately on social media. Therefore, you have to learn patience, and that can be a challenge. However, the virtue of patience has profound spiritual and practical implications. In an age of instant gratification, cultivating patience is a virtue.

It also challenges the photographer to cultivate a spirit of hope, because you will not know for a while whether what you had hoped to accomplish in your framing, focus and exposure will result in a successful image. Plus, by the time you do know, it's generally too late to go back and recreate the moment.

One of the greatest benefits of analog photography is that it encourages a new way of seeing the world. Additionally, as one article explains, the lack of mediating digital technology "helps us pursue an unfiltered connection with our own creativity." Knowing my options are limited, I have found myself looking more deeply at my surroundings, seeing how the light is operating, considering the details of a scene, and recognizing the beauty of the people and world around me, even when I don't have a camera in hand.

I am grateful for this resurgence of analog photography in general, but I am also encouraged by the spiritual benefits that come with slowing down and seeing anew. Discerning God's presence in the world through the lens of a camera is a humbling and exciting experience. I am not alone in recognizing the connection between photography and the spiritual life. In recent years, several authors have explored these themes, including Christine Valters Paintner in her The Eyes of the Heart: Photography as a Christian Contemplative Practice and Philip Richter's Spirituality in Photography: Taking Pictures with Deeper Vision.

For those who would like to see how photography has been a rich expression of spirituality for others, I highly recommend the recent book Beholding Paradise: The Photographs of Thomas Merton, edited by Paul Pearson, the director of the Thomas Merton Center. Merton was one of the greatest spiritual voices of the 20th century; this volume invites us to see his spiritual vision too.

As for me, I plan to continue embracing my rekindled love of photography —analog and digital alike — striving to make it a spiritual practice as much as it is a creative one.

A different kind of selfie: With walking around my neighborhood being one of the few things I could safely do during the pandemic, I started taking a camera with me to capture what I might see. (Daniel P. Horan)