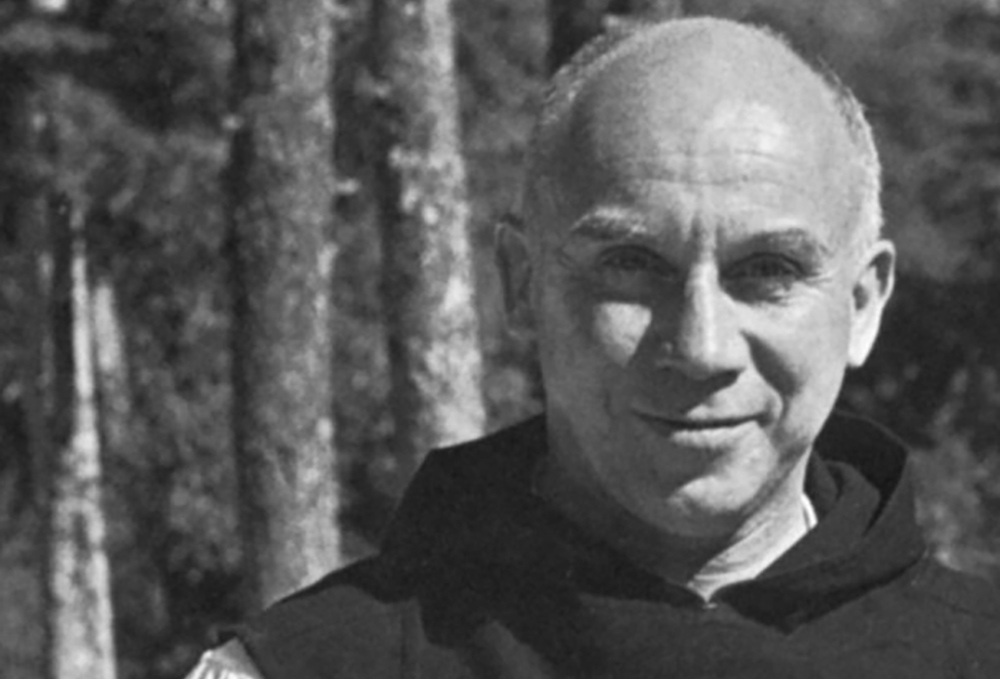

Trappist Fr. Thomas Merton in 1968 (CNS/Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University)

Today marks the start of the 17th biennial conference of the International Thomas Merton Society. This year's conference theme, "Thou Inward Stranger," comes from a line in one of Merton's poems. It was selected by the planning committee (of which I am a part) to frame the academic and pastoral reflections that will be presented in the coming days on contemplation, the manifold forms of alienation that exist personally and collectively in our world, and ways the wisdom of the Christian tradition and Merton's own prodigious contributions might help us respond to the challenges of our day.

Naturally, I have been thinking a lot about Merton, his work and legacy as this conference has drawn nearer. But in the wake of last week's meeting of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops and the imprudent insistence of many bishops on forging ahead in drafting a document ostensibly targeting President Joe Biden and other Catholic politicians with the threat of withholding the sacraments, I found myself returning to some of Merton's writings from the mid-1960s that focused on ecclesial and social crises of the era.

He opens his 1964 essay "The Christian in Diaspora" with a reflection on a then-recently published book by the renowned German theologian Jesuit Fr. Karl Rahner titled The Christian Commitment. The first line of Merton's essay reads: "It is no secret that the Church finds herself in crisis, and the awareness of such a fact is 'pessimism' only in the eyes of those for whom all change is necessarily a tragedy."

He continues, "It would seem more realistic to follow the example of Pope John (and of Pope Paul after him) and to face courageously the challenges of an unknown future in which the Christian can find security not, perhaps, in the lasting strength of familiar human structures but certainly in the promises of Christ and in the power of the Holy Spirit. After all, Christian hope itself would be meaningless if there were no risks to face and if the future were definitively mortgaged to an unchanging present."

Part of what contributes to the crisis is the refusal of many bishops to recognize the ongoing creative power of the Holy Spirit.

It's striking how timely those opening observations are 57 years later. Indeed, the church, at least within the United States, is facing a crisis. And, as I have written here before, part of what contributes to the crisis is the refusal of many bishops to recognize the ongoing creative power of the Holy Spirit. Instead, they double down on their own sense of self-assurance and the mistaken belief that they — and they alone — are responsible for the success or failure of Christ's church.

This is part of what I see playing out in their reduction of the Blessed Sacrament to an idolatrous token of political partisan approval or as a blasphemous weapon to be used in controlling the people of God.

When you think everything is all up to you and forget that it is only God's place to judge the fittingness of an individual Christian, then you start to do some really inappropriate things, like rejecting the inherent synodality of episcopal collegiality or the expressed instructions of the Vatican's Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith to take a more responsible theological, canonical and pastoral course.

There is a dangerous irony in the crisis that besets the U.S. church, which is what I believe alarmed Cardinal Luis Ladaria, prefect of the doctrinal congregation, and led to his warning the U.S. bishops; namely, that the primary role bishops serve is to symbolize and safeguard communion of the local churches with the universal church.

This is why the presider names both the local bishop and the pope in the Eucharistic Prayer at Mass. And this is what the fracturing of the U.S. bishops' conference and the breakdown of episcopal collegiality threatens.

This is dangerous not because a single politician or group of public figures receiving the Eucharist according to their consciences threatens the coherence of sacramental theology or causes grave scandal, as some bishops insist, but because many of the culture-warrior bishops themselves are signaling that they are increasingly less interested in maintaining communion with one another and with the bishop of Rome.

Advertisement

And that is a real ecclesial crisis.

If, as I believe it is the case, part of what motivates these kinds of episcopal judgments and behaviors is fear of change and loss of power, perhaps Merton's reading of Rahner's reflection on the modern "diaspora situation" of the church today, which describes Christianity's relationship to the modern world as noninsular and diffusive, can be instructive.

Rahner argued that Christendom and the Christian cultural hegemony of the Middle Ages, which some people nostalgically pine for, is not only gone but is also impossible to retrieve. More than half a century later, we still hear Christians, including some church leaders, speak as if such a context could and ought to be recovered.

Rather than attempting to reconstruct a past that may or may not have ever existed, Rahner argued that the Holy Spirit continually renews the church and world, which is a sign of what Merton calls "valid Christian hope."

Accordingly, Merton argued that recognizing this valid Christian hope has two significant implications.

First, church leaders today need to "admit that the diaspora situation is one where clerical action will be frustrated and impeded, and to accept this fact is not, for Rahner, to admit defeat. On the contrary, refusal to accept this means that the Church's energies in the diaspora will be dissipated in useless and frantic struggles to assert clerical authority where that assertion has relatively little apostolic meaning or usefulness, and where much greater good would be done by another approach."

In this way, Merton offers a prescient and keen diagnosis of the current actions of church leaders in the United States today, and the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith's instruction to proceed "by another approach."

In the efforts of many U.S. bishops to grasp onto what they consider issues able to restore their power and authority, they actually concretize their decreasing relevance.

The second implication is that this context of "diaspora" requires the laity to fully embrace their baptismal vocation as full members of the body of Christ. There is no hermetically sealed Christian enclave in which to seek refuge, because it is up to all Christians to bring the Gospel of Jesus Christ to the world and to be "missionary disciples," as Pope Francis explains in Evangelii Gaudium.

The church is, after all, all the baptized united in the Holy Spirit (Lumen Gentium) and therefore it is not merely up to a powerful and exclusive clerical elite alone to do the work of Christ in the world. Such a distorted ecclesiology, while still popular in some circles, reflects neither the ancient tradition as found in the New Testament and among early church theologians, nor in the current church teaching as expressed by the Second Vatican Council.

Paradoxically, many of the bishops who espouse this worldview fear the ecclesial and social reality as it actually is and, in their efforts to grasp onto what they consider issues able to restore their power and authority, they actually concretize their decreasing relevance.

Returning to the International Thomas Merton Society conference theme this week, one might reasonably assume that a commitment to the Gospel and Christian faith in a secular world could lead Christians to be strangers in society. But, sadly, what we see with certainty on display today with the church in crisis is a large number of American bishops actively choosing to become strangers in their own community of believers.