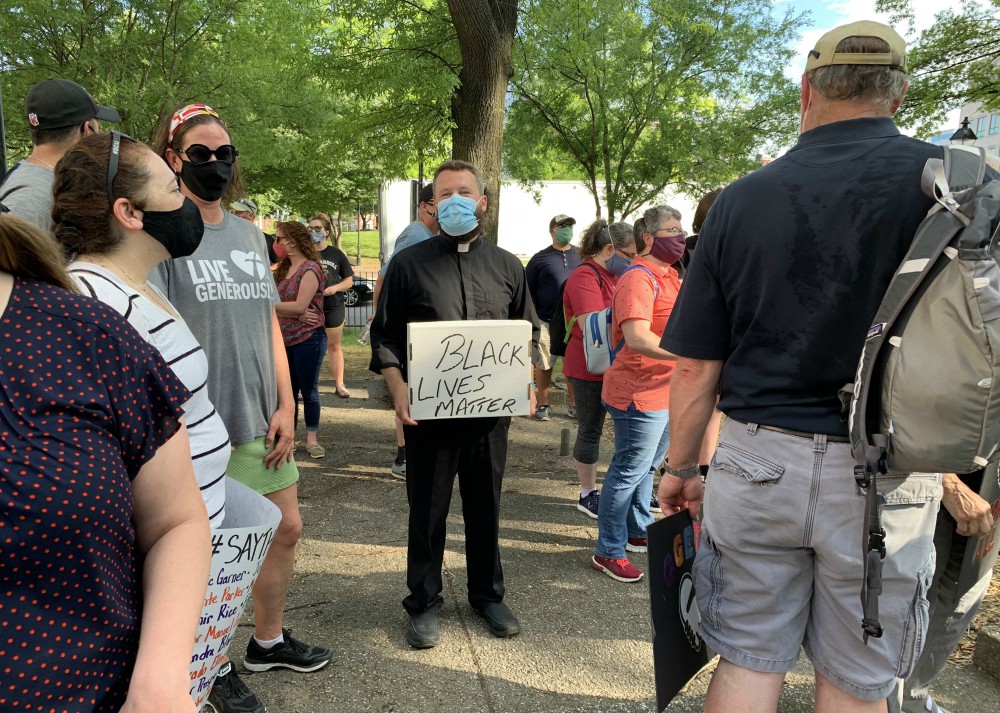

Fr. Joshua Laws, pastor of the Catholic Community of South Baltimore, holds a "Black Lives Matter" sign before the start of an interfaith prayer vigil in Baltimore June 3 to pray for justice and peace following the May 25 death of George Floyd. (CNS/Catholic Review/Tim Swift)

The time for niceties is long over and the choreography of oblique critique is beyond tiresome. The urgency of the moment demands honesty; therefore I will be blunt: The 2018 U.S. bishops' conference document "Open Wide Our Hearts: The Enduring Call to Love — A Pastoral Letter Against Racism" has effectively proven to be a worthless statement. And nothing has made that clearer than the events over the last few weeks following the modern-day lynching of Ahmaud Arbery in Georgia and the police murders of Breonna Taylor in Louisville, Kentucky, and George Floyd in Minneapolis.

Last year, not long after the pastoral letter was released, I wrote about many of the text's stark inadequacies, something likewise noted in other venues such as the Pax Christi USA and Sisters of Mercy websites, and by Fordham University theologian Fr. Bryan Massingale in, among other places, interviews last week with America and Commonweal magazines.

I conceded in last year's column that the bishops and their advisers may have meant well, even said many good things, but nevertheless failed to do what was required of them in addressing the evil of systemic racism head-on.

Instead of speaking the uneasy yet necessary whole truth, the bishops' document contorts into passive voice and platitudes of kindness; it speaks of the sin of racism, but never names the sinner. While the title of the recent pastoral letter is an improvement on that of its 1979 predecessor — "Brothers and Sisters to Us" — its content makes no discernable progress in addressing the persistent and systemic evil of racism and the white supremacy of the church and this nation that perpetuates it.

Over time, I have recognized my obligation to acknowledge the multitude of unearned privileges from which I benefit — as a cisgender white man, an ordained member of a religious order, a documented citizen of the United States, a nondisabled and neurotypical individual, someone with a private college education and graduate degrees, among others — so I can gain perspective, orient myself to the task of self-education about racial injustice, do my part from my particular location to dismantle white supremacy.

I have learned a lot, but I know I have much more work to do. And because of this ongoing experience of learning and growing, which has often been painful and uncomfortable as it has been enlightening, I feel that I can both empathize with and offer constructive critique to the bishops with whom I share fraternity as a brother priest.

Advertisement

The church in the U.S. needs a document that does not spare the feelings or prioritize the comfort of white people like me. The reality of racism requires an honest acknowledgement of the basic truth that racism is a white problem and progress will only be made when church leaders accept and preach this fact. As Massingale stated frankly in his Commonweal interview, "If it were up to people of color, racism would have been over and done, resolved a long time ago. The only reason that racism continues to persist is because white people benefit from it."

So why haven't the U.S. bishops collectively done their pastoral duty to address this pervasive social sin? According to the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops' website, there are currently 427 active and retired bishops in the United States. Of that number, according to the conference's own data, only 13 of the active and retired bishops are of African descent. This statistic is important for several reasons.

First, when taken with the similar disproportionately small number of Latino bishops and bishops of Asian descent, the vast majority of American bishops are white. As an overpoweringly white group, they are shielded from the full truth of their complicity and privilege by the very mechanism and logics of white supremacy.

Second, those bishops from minoritized communities are likely to be, historically speaking, disinclined from correcting their white episcopal brothers on these matters, given the overwhelmingly white space the U.S. bishops' conference represents. Furthermore, it is not the responsibility or obligation of persons of color generally, and the bishops and conference staffers of color specifically, to educate the majority white episcopate. It's the responsibility of white people to educate themselves about racism and white supremacy. And engaging, citing, teaching the work of experts on racism — especially experts of color in and outside the church — is an absolute necessity.

Third, according to U.S. bishops' conference data, there are approximately 37,302 ministerial priests in the U.S., and of that number only 250 are identified as African American. That means that African American priests account for 0.7% of the total number, a startling statistic that further reveals the hegemony of white experience, perspective and culture in ecclesiastical leadership at the parish, diocesan and national levels.

A group of U.S. bishops making their "ad limina" visits to the Vatican arrive to concelebrate Mass at the Basilica of St. Paul Outside the Walls in Rome Dec. 11, 2019. (CNS/Paul Haring)

Fourth, while the numbers alone do not account for (and never justify) white normativity in the U.S. church, the fact that there are hundreds upon hundreds of white bishops who determine policy, vote on the content and language of teaching documents, and offer statements that are supposed to speak for the American Catholic community writ large contributes to the maintenance of the status quo and is likely to consciously or unwittingly prioritize white comfort over the safety and experience of communities of color.

It is this last point that is worth reflecting on for some time. The U.S. bishops' conference, despite best intentions, refused to engage in the long overdue self-criticality required to make real progress in addressing racism.

The reason the 2018 pastoral letter fails at addressing racism in a meaningful way is that it is presented in such a manner that the majority of white bishops, priests, religious and laity in the U.S. could feel good about "doing something" while also never having their comfort and worldview challenged in a substantive fashion.

Yes, we can all agree that racism is sinful and an evil to be rejected, but what about the source and perpetuation of structures and institutions of racial injustice? What about naming and challenging those who, like the enormous majority of priests and bishops in the U.S., including me, benefit from the continuation of systemic racism?

This is something Massingale touches on in his interview with Commonweal. He explains: "The document was written by white people for the comfort of white people. And in doing so, it illustrates a basic tenet of Catholic engagement with racism: when the Catholic Church historically has engaged this issue, it's always done so in a way that's calculated to not disturb white people or not to make white people uncomfortable."

The detrimental consequences of prioritizing the comfort of white people over addressing the hard truths of racial inequality and injustice is something that many writers have considered in recent years, including in important works by George Yancy, Ijeoma Oluo and Robin DiAngelo, among others.

Within an ecclesial context, I was reminded of something St. Óscar Romero of El Salvador once preached: "A church that doesn't provoke any crises, a gospel that doesn't unsettle, a word of God that doesn't get under anyone's skin, a word of God that doesn't touch the real sin of the society in which it is being proclaimed — what gospel is that?"

Romero eventually understood the stakes of proclaiming uncomfortable truths mandated by the Gospel and he paid the price with his own blood. Comparably, the risk to the majority white episcopate in the U.S. is far less dire. Still the fear of retaliatory anger, the withholding of financial contributions by wealthy benefactors, the perception of succumbing to "identity politics" or, worse in some circles, "political correctness" drives the promulgation of nonthreatening statements that move the hearts of no one.

I agree with Massingale that the 2018 document "really is woefully inadequate to the challenge of the time." What the outrage, mobilization and protests of recent weeks have shown is that this may be a kairos moment, a divinely appointed time for putting into action real Gospel convictions about justice.

Some, like Bishop Mark Seitz of El Paso, Texas, have recognized this. But most others still haven't. If now isn't the time, when is?

The U.S. bishops' refusal to risk discomfort or take on a share of the pain of racial injustice means that they — as an overwhelmingly white ecclesiastical body — are forcing people of color to, as Oluo says, "continue to bear the entire burden of racism alone."

This sort of behavior is what the Catholic tradition calls sin. And what is currently presented by the U.S. bishops as a pastoral letter on racism is, at the very least, indicative of a sin of omission. Which is why it is beyond time for the bishops to acknowledge what Catholic leaders, religious, laity and institutions have done and have failed to do when it comes to racism; to call out their own complicity and participation in unjust structures; and to risk making themselves vulnerable and other white Catholics uncomfortable as an authentic start to a meaningful pastoral document.

[Daniel P. Horan is the Duns Scotus Chair of Spirituality at Catholic Theological Union in Chicago, where he teaches systematic theology and spirituality. His recent book is Catholicity and Emerging Personhood: A Contemporary Theological Anthropology. Follow him on Twitter: @DanHoranOFM.]

Editor's note: Don't miss out. Sign up to receive an email notice every time a new Faith Seeking Understanding column is published.