Kaya Oakes, left, and Ryan Burge, center, listen as Tara Isabella Burton speaks during a symposium on "God, Religion and the 'Nones' " Oct. 15, at Fordham University in New York. (CNS/Fordham University)

Nearly nine years ago, I covered a full day symposium at Fordham University called "Lost? Twenty-somethings and the Church," sponsored by the university's Center on Religion and Culture.

The event was primarily concerned with three questions: Have young adult Catholics lost their way? Has the church lost twenty-somethings? And, if so, how do we get them back?

Those inquiries were apparently so urgent that the center had to open up a second auditorium and livestream the program to accommodate the overwhelming number of registrants.

The interest was stimulated by a stark reality: The Catholic Church in the United States was hemorrhaging numbers, with two-thirds of Americans who were raised Catholic no longer attending church.

This week, Fordham's Center on Religion and Culture offered a similar, but smaller scale program that felt like a post-"Lost?" check-in: "Does Faith Have a Future? A Symposium on God, Religion, and the 'Nones.' "

And while, nearly a decade later, the lack of interest in institutional religion remains the same, the questions we need to ask have changed.

Or at least they should, said Kaya Oakes, the Oct. 15 event's opening panelist and author of the 2015 book The Nones Are Alright: A New Generation of Seekers, Believers, and Those In Between.

"The better questions we should ask instead of how to get the nones back is, where do we meet them and what do they need?" said Oakes.

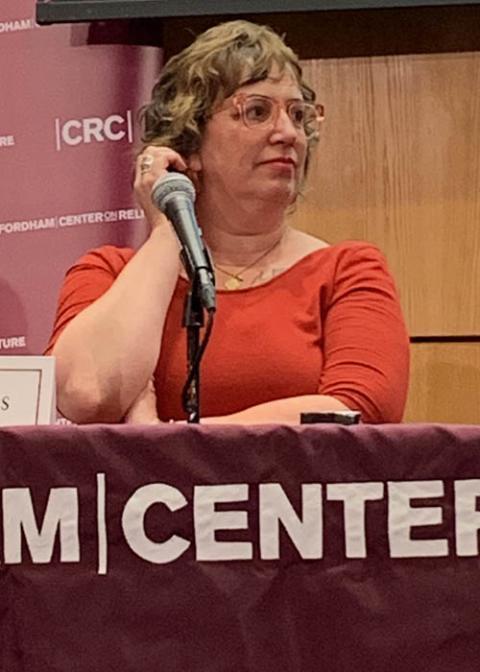

Kaya Oakes (Jamie Manson)

She offered pointed critique of Auxiliary Bishop Robert Barron of the Archdiocese of Los Angeles, whose Word on Fire Catholic Ministries aims to bring the nones into the fold.

"He's obviously very concerned" about the nones, Oakes said, and yet his use of catechetics gives "the feeling he's never met one."

"He doesn't ask why they left, but only how can we get them back," she said, adding, "there are no stats to suggest that buying Word on Fire merchandise can retain young Catholics."

Oakes says Barron's rhetoric creates a danger of making nones the "other," which creates a problematic "us versus them" dynamic.

"A lot of what he says is from a very clerical point of view," said Oakes. "He should spend time with them rather than telling them what they should do."

Oakes says she recently studied with the Jesuits to become a spiritual director, and when she put out a call for directees, she received "a massive responsive from the nones group." So much so that she had to turn many of them away.

"The things that were secure for previous generations are no longer there," such as affordable housing, stable full-time work and manageable education costs, she said. "We need to meet people where they are."

Oakes has been intentional about not using the term "nones," preferring instead to call them the "religiously unaffiliated."

"It's a negation," said Oakes, that is not reflective of their spiritual longings.

A second panelist, Tara Isabella Burton, also questioned whether the term "nones" should be used at all.

The author of the forthcoming book, Strange Rites: New Religions for a Godless World, Burton says that the nones nomenclature is "profoundly incorrect."

According to her research, "About 72% of the self-identified religiously unaffiliated say they believe in a higher power of some sort and about 20% say they believe in the Judeo-Christian God."

"There is an enormous number of people," Burton said, "who see themselves as spiritual persons, who have a spiritual hunger."

Burton said her forthcoming book questions what that spiritual identity is and what it means for the future of faith.

"Can we speak maybe not of a formal, codified religion, but of religious strains or ideological strains within that group?" she asked.

Panelists Kaya Oakes, Ryan Burge and Tara Isabella Burton, Oct. 15 at Fordham University in New York (Jamie Manson)

It is precisely the intertwining of religion with ideology that is the source of the decline in religious affiliation, said Ryan Burge — particularly Republican political ideology.

"The cause of and solution to all of our problems is politics," said Burge, a Baptist pastor and assistant professor of political science at Eastern Illinois University.

When Fordham last held that conference on young adults and the church, the election of Donald Trump was unthinkable. But in those intervening years, both mainline Protestants and Catholics have become more politically and religiously conservative. And that has had a profound impact, Burge posits, on millennials' disenchantment with Christian organized religion.

"If you attend a white Protestant church in 2018, there is basically a 93% chance you're going to attend a church where Donald Trump is liked more than he is liked in the general public."

And the news is just as sobering for Catholics, said Burge, whose 2018 research data suggests that 52% of white Catholics say they would vote for Trump again in 2020.

"White Catholics are getting more conservative as well," said Burge to a groaning audience. "The only thing that holds them largely toward the middle is Latino Catholics."

"If you're a white person coming of age in America at 20 or 22 years old, and you want to vote for a guy like Mayor Pete or even Joe Biden," he said, "you're going to go to a church where you don't find a lot of kindred spirits in the pews with you."

Ryan Burge (Jamie Manson)

Burge drew on the sociological concept of the "spiral of silence," to explain the situation.

"It's the idea that if you're in the minority, you figure it out pretty quickly. So what do you do? You close your mouth," said Burge. "And you know what happens when people hear silence? They think it's complicity."

If you're not speaking up against the group, they think you agree with them, and the spiral of silence gets worse and worse, he said.

Though there are lots of Americans who are not Republicans, Burge said, when they think about religion, "they think about the secular left or the religious right, and they don't fit in either camp. So on Sunday it's just easier to not show up."

But who exactly is not showing up to church is more broad-based than one might assume, said Alan Cooperman of the Pew Research Center. Cooperman offered slide after slide of Pew's statistics demonstrating that disaffiliation from religion is increasing among mainline Protestants, Evangelicals and Catholics.

According to data presented at the event, 35% of millennials and 23%* of Gen-Xers identify as unaffiliated. Pew Research Center released an update Oct. 17, reporting that over the past decade, "the number of religiously unaffiliated adults in the U.S. grew by almost 30 million."

And it's across the country, "not just a coastal thing," Cooperman said at Fordham.

It's also not just a white issue.

"Disaffiliation is also increasing among people of color and among other racial ethnic groups in the United States," Cooperman told the audience. "We are hard pressed to find any part of the U.S. population where this is not taking place."

Alan Cooperman (Leo Sorel)

The traditional wisdom is that as people grow older, have children and begin to face the reality of death, they become more affiliated with religion. But Pew's latest research suggests that pattern is no longer the case.

"No recent generation has become more religiously affiliated as it has gotten older," said Cooperman, "and each generation has started out less affiliated than the previous one."

Catholics, he said, continue to be the biggest losers in this numbers game.

Only 59% of people in the U.S. who were raised Catholic still claim a Catholic identity. And for every one person who joins the Catholic Church, another 6.5 leave. This is a stark contrast to mainline Protestants, who have 1.7 persons leave for every one person who joins, and evangelical Christians, who gain 1.2 persons for every one person who leaves.

The biggest winner, unsurprisingly, is the unaffiliated, who gain 4.2 persons for every one person who ends up affiliating with a religion.

Cooperman concluded his show of statistics by offering four theories of why the nones continue to grow.

Like Burge, he postulates that the entanglement between religion and politics has turned people off.

Another theory is that religious groups have been adversely impacted by the decline in the marriage rate.

Though the divorce rate, Cooperman noted, has remained the same, the number of Americans who have never married has increased from 15 percent to 30 percent between 1960 and 2015.

"Families and religion are tied together," said Cooperman, because religious traditions help families mark time and milestones, and families pass these customs on to the next generation.

But what if the rise in disaffiliation has nothing to do with religion, but, rather is a symptom of a broader social change?

Advertisement

Hearkening back to Robert Putnam's classic sociological study Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community, Cooperman said the decline in civic engagement and fraternal organizations has led us to lead more "atomized lives."

In the same way an atomizer breaks up a liquid into thousands of tiny drops, this shift in culture has made us act in increasingly individualistic ways — a reality that has only been enhanced and encouraged by our cellphone usage and even our social media habits, which are also largely engaged in solitarily.

The last theory has to do with affluence and what Cooperman labeled "existential insecurity."

"There is a clear overall pattern that the richer the country, the less religious it tends to be," said Cooperman, who showed a graphic to demonstrating this global research.

The only outlier? The United States, which is as rich as it is religious. (Cooperman noted that the statistics might be similar in wealthy Islamic countries like Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, but those countries do not release this kind of data.)

China is the only country that is both poor and nonreligious, owing largely to its Communist history.

Whether or not this decline in religious affiliation is a good thing or a bad thing, Cooperman says, depends on what the reason is.

If one thinks that younger people are turning away from religion because of scandals and hypocrisy, then maybe it's a good, or at least justified, thing.

"In a competitive world it's a wake-up call," Cooperman said. "If that's the cause, maybe it's time for change. If religions can do better, maybe future generations will come back. "

But, at the same time, if this is about the "bowling alone theory," it's not great news.

Volunteering and charitable giving are down, Cooperman noted. And if the decline in religion is just one symptom of a broader breaking apart of our sense of community and who we are as a society, we may be in more trouble than we realize.

What no one seems to have an answer for, Cooperman concluded, is this question: "How do we get out of this?"

[Jamie L. Manson is NCR books editor and an award-winning columnist at the National Catholic Reporter. Follow her on Twitter: @jamielmanson.]

*This story has been updated to correct a statistic.

Editor's note: We can send you an email alert every time Jamie Manson's column, "Grace on the Margins," is posted to NCRonline.org. Sign up here.