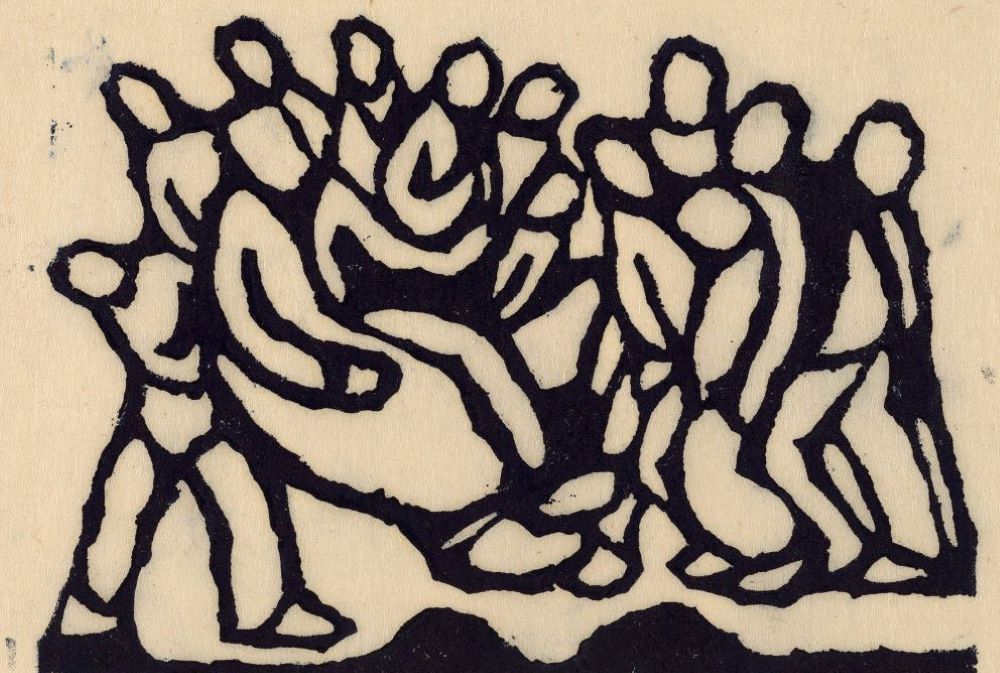

"Christ before the High Council," 1913, by Wilhelm Morgner (German, 1891-1917) (Artvee)

During Holy Week this year, Catholic congregations will hear, and in some cases enact, the passion narratives from the Gospels of Matthew and John.

Matthew 27:25 uniquely depicts a Jewish mob crying, "His blood be on us and on our children!" This sentence was the basis of the later idea — widespread among Christians and their leaders for centuries — that Jews in all times and places were cursed by God and sent to wander, powerless, among the nations.

The Gospel of John is distinctive for its frequent collective use of the phrase "the Jews" as implacable foes of Jesus, setting up a dualism that allowed Christians to make Jews symbols of darkness and evil. In its passion narrative, "the Jews" declare, "We have a law, and according to that law he ought to die because he has claimed to be the Son of God" (John 19:7).

History shows that without guidance Christians easily read such texts as justifications for anger and hostility toward Jews. This is because they assume the Gospels are eyewitness transcripts of historical events rather than as narratives driven by resurrection faith. Unlike fundamentalists who do not "take into account the development of the Gospel tradition, but naively confuse the final stage of this tradition (what the evangelists have written) with the initial (the words and deeds of the historical Jesus), Vatican commissions have instructed Catholics that the Gospels can "reflect Christian-Jewish relations long after the time of Jesus."

The way that the Gospel authors told the story of Christ’s passion has embedded in the Christian religious imagination the binary notion that "Judaism" and "Christianity" are existentially opposed to each other.

Written decades after the crucifixion, the Gospels emerged at a time when believers made claims about Jesus' divine status that left many Jews unpersuaded. These arguments shaped the Gospel narratives of the stories of Jesus' passion, contributing to angry portraits of Jewish antagonists not of Jesus' time, but of the Gospel writers' own.

How many Catholics are aware of this complex history of the Gospels? Fortunately, beginning in 2024 the text of John's passion narrative in missals will be immediately preceded by a note based on the Second Vatican Council declaration Nostra Aetate:

The crimes during the Passion of Christ cannot be attributed, in either preaching or catechesis, indiscriminately to all Jews of that time, nor to Jews today. The Jewish people should not be referred to as though rejected or cursed, as if this view followed from Scripture.

The placement of this note just before John's passion text is an improvement over previous notes that were less likely to be noticed because they were placed inside the missals' covers.

But there is a larger issue at stake. The way that the Gospel authors told the story of Christ's passion has, over the centuries, embedded in the Christian religious imagination the binary notion that "Judaism" and "Christianity" are existentially opposed to each other.

This is evident in a draft of an encyclical prepared in 1938 for Pope Pius XI, whose death scuttled the initiative: "As a result of the rejection of the Messiah by His own people … we find a historic enmity of the Jewish people to Christianity, creating a perpetual tension between Jew and Gentile which the passage of time has never diminished."

Christians who operate with this kind of "oppositional imagination" find it difficult to visualize Jesus as living Jewishly. A kind of "de-Judaizing" process, as the U.S. bishops put it in a 1975 Statement on Catholic-Jewish Relations, is at work. In its most dangerous form, the result is the Aryan Jesus of the Nazis. But less extremely, certain Gospel passages can be read through oppositional lenses as if Jesus were an outsider to Judaism, rather than a Jew devoted to the Torah and its proper interpretation.

Christians with the oppositional imagination can tend to contrast the teachings of Jesus with certain Old Testament texts that portray God as angry or punishing, overlooking those exceedingly numerous verses that summarize Israel's experience of God as one who is "merciful and gracious, slow to anger, and abounding in steadfast love and faithfulness" (Exodus 34:6). They also tend to ignore New Testament references to a punishing God, such as Revelation 20. Those who make such contrasts are, without realizing it, exhibiting a form of Marcionism, an ancient heresy that contended that the deity of the Old Testament was not the God of love revealed by Jesus Christ.

"Crucifixion I," 1913, by Wilhelm Morgner (German, 1891-1917) (Artvee)

During Holy Week, Christians who imagine Judaism and Christianity as opposed will read or hear the Gospel passion narratives in ways that highlight the roles of Jewish figures and minimize the crucifixion's essentially Roman character. Some versions of the passion narratives may, for example, characterize Jewish religious leaders as watching Jesus "with suspicion" and highlighting "opposition" as the cause of Jesus' death.

The phrase "religious leaders" automatically and ahistorically shifts responsibility from Roman to Jewish figures. By not specifying the Jewish leaders as priests, Pharisees, Herodians or anti-Roman agitators (some of whom opposed Jesus, some of whom admired him), this wording implicates Judaism at large. It also perpetuates a Christian caricature of Jewish observance of the Torah and situates Jesus as in fundamental opposition to it.

Nevertheless, certain historical facts make it impossible to regard the execution of Jesus as a predominantly "religious" and so "Jewish" affair. First, "the Jews" cannot be said to have "rejected" Jesus for whatever reason because most Jews would never have heard of him when he was executed; twice as many Jews lived outside the land of biblical Israel than within it at the time.

Second, Jesus was executed during the Passover season when Jews from around the Mediterranean streamed to Jerusalem to celebrate freedom from foreign enslavement. Roman troops brutally repressed any hint of resistance to their rule that typically erupted during the festival.

Advertisement

Third, over time Roman forces crucified tens of thousands of Jews to terrify the people and crush rebellion. Jesus' execution was horribly routine, in fact briefer than most crucifixions. That Jesus was publicly tortured and not quietly dispatched shows that to the Romans he was just one more Jew to make an example of.

Fourth, the high priest of the Jerusalem Temple served in that role at the pleasure of Pontius Pilate. Pilate was eventually deposed by Rome after slaughtering hundreds of Samaritans, while the high priest's fears that the Romans might eventually destroy the Temple (see John 11:48-50) were realized 40 years later.

The point is that the meritorious Catholic teaching that "what happened in [Jesus'] passion cannot be charged against all the Jews, without distinction, then alive, nor against the Jews of today," does little by itself to counteract the baleful influence of the oppositional imagination. If preaching and teaching regularly and inaccurately present Jesus as opposed to Jewish legalism, with unspecified "Jewish leaders" shown rejecting him for post-resurrectional reasons, and with Roman interests discounted, then the long habit of thinking of Jews as enemies of Christ and the Church will persist. The Catholic Church's appreciation of "the wholly unique 'bond' which joins us as a Church to the Jews and to Judaism," as one Vatican instruction put it, will be undercut. This danger is not just an issue in Holy Week, but throughout the year.