Detroit Auxiliary Bishop Thomas Gumbleton in 1985 (NCR photo/Vincent Golphin)

Editor's note: This is an edited version of an address Robert Ellsberg delivered in July 2023 to celebrate the publication of No Guilty Bystander, the biography of Bishop Thomas Gumbleton, who died April 4, 2024. This address was first published by Pax Christi USA, which has given permission for it to be reprinted here.

I first met Bishop Gumbleton in the late 1970s. I was the managing editor of the Catholic Worker and Bishop Gumbleton had invited me to Detroit to speak at a conference on peace. My assigned topic was "Youth and the Arms Race." For the first and last time in my life, I found myself the designated voice of my generation.

I don't remember what I said — I'm sure it was not very memorable. But what I remember was Bishop Gumbleton's humility and kindness, his deep commitment to peace, and his evidently genuine interest in listening to what this "youth" had to say.

I was not raised in the Catholic Church. My introduction to Catholicism at that point was largely by way of Dorothy Day and Daniel Berrigan. And, so, I assumed that Bishop Gumbleton was a pretty typical bishop! I had a lot to learn.

My confidence in Bishop Gumbleton and his fellow U.S. bishops was soon confirmed by their work on "The Challenge of Peace: God's Promise and Our Response," the historic 1983 pastoral letter on nuclear war, which for a short time encouraged speculation that the Catholic Church was on its way to being a "peace church." But, before long, that high-water mark of Catholic social teaching in this country was relegated to the past. The arms race continued unimpeded; the Doomsday Clock of the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists continued to tick closer to midnight.

Detroit Auxiliary Bishop Thomas Gumbleton addresses the U.S. bishops about the situation in Iraq at the start of their annual fall meeting Nov. 10, 1997, in Washington. Gumbleton had visited Iraq in early September on a humanitarian mission. (CNS/Nancy Wiechec)

Some of you knew my father, Daniel Ellsberg, who died in June 2023. He was greatly inspired by the peace pastoral, which he studied carefully — acknowledging its limitations, yet encouraged by hope that this would mark a start rather than an endpoint of the discussion.

Just a few years ago he asked me, "What are the odds that the bishops today could once again take up the question of nuclear war?" I said: zero. But that's a long story.

Yet it makes one wonder about that crossroad, and what the church in this country might look like if it had taken a different path — that is to say, if Bishop Gumbleton had represented, as I once imagined, a more typical bishop.

There is a movie in which a character played by Al Pacino says he has reached a crossroad in his life, and he always knew the right path, but without exception he didn't take it, because, as he says, the right path "was too damn hard."

Bishop Gumbleton has faced many crossroads in his life. And often the right path was the harder one. And yet without exception he always followed what he believed was the right path, not the safe one, not the one that would ensure his own comfort or advancement.

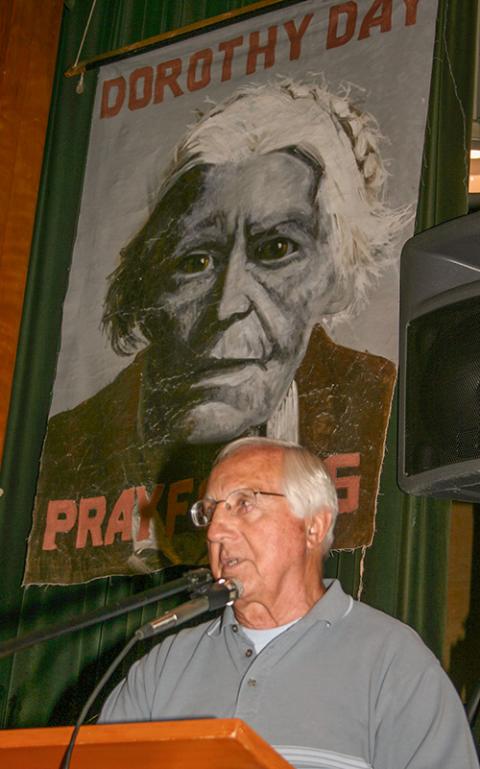

Bishop Thomas Gumbleton speaks at the Catholic Worker movement's 75th anniversary celebration at Our Lady of Mount Carmel-St. Ann Church and Parish Center in Worcester, Massachusetts, July 10, 2008. (CNS/Catholic Free Press/Tanya Connor)

Yesterday, I was giving a talk about Dorothy Day and someone asked if I agreed with all her positions, all her choices. I said probably not. But I said the striking thing about Dorothy was not that she was necessarily correct in every choice or decision — she was not endowed with infallibility! But with every decision she examined her conscience, and she was guided by what she thought was right, what she believed was the way of Jesus, and there was no daylight between what she said, what she believed, and the way she lived. I believe the same is true of Bishop Gumbleton.

That is not to say he has always been right. If that were true, it would mean he was incapable of growth or conversion, and what is clear is that Bishop Gumbleton's whole life has been a long story of conversion, of always striving to go deeper in the call to be faithful.

And in that story of conversion his world seemed to grow steadily larger, rooted in his city and his local parish — but always expanding to encompass new causes, new continents, new communities of people who were left out or forgotten, until his parish seemed to encompass the whole world: as wide as the community of saints and peacemakers and fighters for justice, both living and dead.

And what I find most inspiring about him is not that he has all the correct answers in advance — but that he is always listening, always willing to grow, to change his mind, always willing to take one new step on a path that is uncertain, even at the risk of his reputation, his status, even his physical safety, if that takes him one step closer to Jesus.

Advertisement

How different the church would be if we could say that those qualities make him a typical bishop.

I remember Jon Sobrino, the Jesuit theologian from El Salvador, reflecting on the difficulties for Rome in recognizing slain Salvadoran Archbishop Óscar Romero as a saint. Because, he said, that would mean that bishops should be more like Romero. And he said every indication was that the Vatican, in those days, did not want more bishops like Romero.

By the same token, for much of the past 40 years, one could safely assume that the Vatican did not want more bishops like Bishop Gumbleton.

But maybe we are at another crossroad. I have been very moved by the distinction that Pope Francis makes between what he calls a laboratory faith and a "journey faith."

A laboratory faith, he says, is "a compendium of abstract truths," all determined in advance. Such a faith can be inflexible — ill-prepared to deal with the messiness of life or the nature of reality. Presuming to know all the answers in advance, a lab faith may leave us impervious to the surprising promptings of the Holy Spirit.

In contrast, he says, ours is a journey faith in which we meet God along the way. In a "journey faith" there is much that is unknown: The "truth" emerges through experience, through context, through relationships. It implies the capacity for change or conversion — to discover new and unfamiliar truths. In a journey faith, we don't know all the answers in advance. We have to pray, to reflect, to listen to how God is speaking to us through the events of history, or the needs of our neighbors, or the circumstances of our own life.

Retired Auxiliary Bishop Thomas Gumbleton talks with longtime parishioners Linda Maxwell and her nephew, Wesley Maxwell, Jan. 21, 2007, at his last Mass as administrator of St. Leo Parish in Detroit. (OSV News/Michigan Catholic file photo/Robert Delaney)

As Pope Francis notes, "Our life is not given to us like an opera libretto, in which all is written down; but it means going, walking, doing, searching, seeing. ... We must enter into the adventure of the quest for meeting God; we must let God search and encounter us. ... God is encountered walking along the path."

Bishop Gumbleton has been a long-distance pioneer along that path. He was not content to assume that every answer could be found in the Code of Canon Law or the catechism.

I was deeply moved as I read this biography, and saw how often Bishop Gumbleton was challenged to rethink his position or change his mind because he listened to other people, or opened himself to the challenge of experience, or the question to which the familiar answers seemed inadequate. He especially listened to the voices of those who were in pain or suffering, knowing that if he followed the sound of those voices, he would encounter Jesus along the way.

You see that when he goes to talk to some priests who were protesting the war in Vietnam, and his job was to tell them to cool off, but, as he listened to them, he decided that they were right and he joined them.

You see it when his mother asked him if his gay brother was going to hell, and when he says no, he realizes that that means opening a door previously enclosed on judgments and certitudes that were out of touch with the qualities of love and human reality.

Let those who have ears listen.

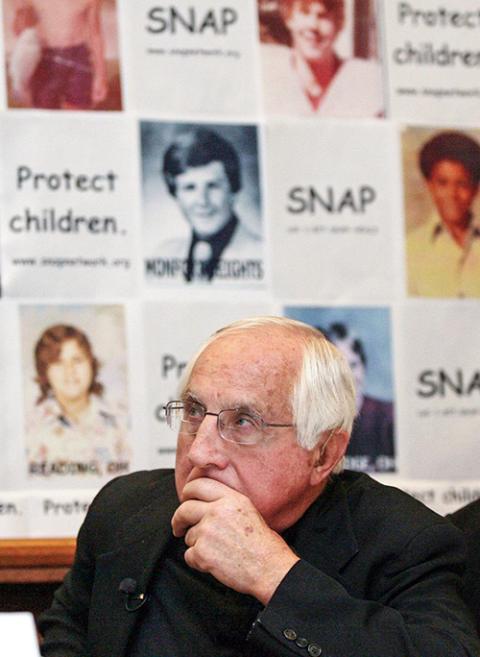

Bishop Gumbleton listened to the voice of Óscar Romero. He listened to the story of Franz Jägerstätter. He heard the cry of those who were hurt or oppressed in Palestine, in the Middle East, Afghanistan, Central and South America, the streets of Detroit, the misery of Haiti, the voices of the victims of clergy sex abuse.

Detroit Auxiliary Bishop Thomas Gumbleton looks on during a Jan. 11, 2006, press conference in Columbus, Ohio, at which he revealed that he was sexually abused by a priest when he was a teenager and spoke in favor of reforms to state child molestation laws. (CNS/Reuters/Matt Sullivan)

He had acquired a dangerous habit of listening! And once he had heard something he could not unhear it. That is why he kept returning to the battle zones, the picket lines and the prisons, the vigils and sit-ins, crossing the line at nuclear tests sites and other militarized zones, confronting poverty and systemic racism, returning again and again to the conventions of Dignity and New Ways Ministry.

And this was not drive-by solidarity; once he took on a new issue or community, these people became part of his parish family.

No doubt certain church officials found his commitments and causes disturbing and even exasperating.

And yet I dare to imagine we are again at a crossroads. I dare say that Bishop Gumbleton exemplifies Pope Francis' actual idea of a typical bishop: a shepherd with the smell of the sheep. A shepherd who touches the wounds of Christ. A shepherd whose hands are rough and soiled from being in the streets. A shepherd, like the Good Shepherd himself, who was drawn like a magnet to people who were excluded, hurting, marginalized.

Yes, I wish there were more bishops like Bishop Gumbleton. But it's a cop-out to ask why there are not more, unless I am prepared to ask, why am I not more like Bishop Gumbleton? I fear the answer is that it seems "too damn hard."

But reading this book inspires me to imagine what it would be like to listen to the voice of Jesus that speaks to me from places where I fear to go, knowing that there are people like Bishop Gumbleton, and Dorothy Day, and Daniel Berrigan, and many others who have been there before.

They don't ask me to be like them, or to be the voice of my generation. Just to be myself: only a little better, a little braver, a little kinder, more loving, more faithful. And to take one more step along the path.