Catholic University of America students and faculty celebrate graduation May 12, 2018. (CNS/The Catholic University of America/Dana Rene Bowler)

America's bishops' university is at a crossroads. As announced last fall, after 11 years, John H. Garvey is stepping down as president of the Catholic University of America and a search is narrowing for his replacement. The stakes are high, not only for the university but also for the church.

As the United States' only pontifical university, its status as "the bishops' university" reflects its bylaws that stipulate that the archbishop of Washington is ex officio chancellor and liaison to the U.S. bishops' conference, from which 18 of its 48 members of the board of trustees must come.

Punching far above its academic weight, CUA (as I still prefer to call it from my time as a former director of an institute there) plays a leading role in the intellectual formation of Catholic leadership in the United States. As its founders envisioned, today about half of U.S. bishops studied at CUA at some point, and church institutions, seminaries, Catholic advocacy groups, religious congregations and Catholic media organizations are replete with its graduates.

The situation the new president will face is daunting. A complex of interrelated problems poses a challenge for which progress can only be slow and the chance of failure high. Not the least of the problems is the perennial question: What does it mean to be a Catholic university?

Advertisement

Indeed, for CUA, what does it mean to be America's only pontifical university, the university of America's bishops, at a moment when Catholicism itself is fraught with an identity crisis, declining religious vocations, demographic erosion, a still cancerous sexual abuse history, and ideological and ecclesiological tensions verging on schism driven by political polarization in the pews and pulpits? Yet this Catholic question is intrinsically linked with the university's other challenges.

Financial exigency

Founded in the late 19th century to be a research university, CUA has, since the 1960s, faced financial exigency that has required greater and greater focus on undergraduate and professional education. Its success in balancing research and teaching has been mixed. Initial efforts to expand undergraduate enrollments went well, but have been far less successful in recent decades — and while striving for undergraduate enrollment, graduate enrollment has declined. It now has about 3,000 undergrads and, depending on how they are counted, about 2,000 graduate students. Most college rankings list its admissions as "more selective," admitting 82% of undergrad applicants.

The university's financial situation is difficult because of its enrollment challenges. It is overwhelmingly tuition dependent for its operation. Despite being under the control of the U.S. bishops, only a miniscule percentage of CUA's yearly budget is covered by America's dioceses. CUA's tiny endowment of less than $280 million pays for very little of its operating costs — compared, for example, to Notre Dame's $12 billion (billion with a B) endowment.

While Garvey and the previous president, Bishop David O'Connell, were successful in cultivating important gifts from big donors, those gifts tended to be targeted at the program level, such as athletics and the business and nursing schools, and not at the bottom line. Moreover, individual gifts to programs often subtly — and sometimes not so subtly — come with a donor's agenda, as some have suggested about recent Charles Koch Foundation and Busch Family Foundation grants to CUA.

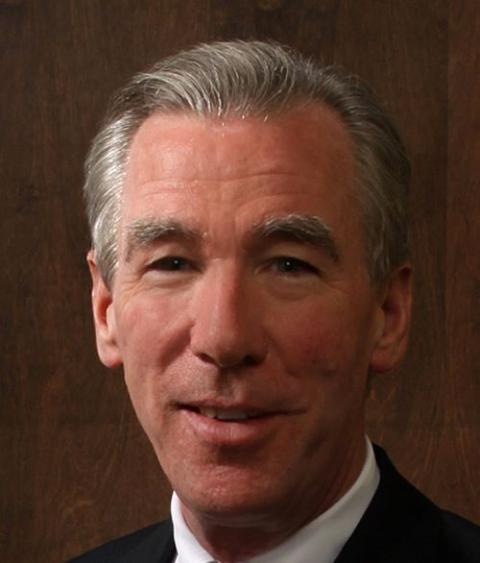

John H. Garvey, president of The Catholic University of America in Washington, announced Sept. 22, 2021, that he would step down from his leadership role June 30. (CNS photo/courtesy of The Catholic University of America)

About halfway through Garvey's tenure, he implemented a significant cost-cutting plan necessitated by enrollment difficulties. A broad buyout of senior faculty (full disclosure: including me), deferred maintenance and cuts in administration positions initially stabilized financial pressures. But that success came at the cost of weakening some academic programs, particularly in the humanities and particularly for graduate studies.

Then, on the heels of those cuts, the impact of the COVID pandemic hit the university hard, which further slashed revenue from enrollments and forced the administration to seek salary cuts from faculty and staff. Garvey himself took a 20% cut, but CUA salaries, which were already quite low compared with its peer universities, fell yet another notch, impacting the morale of faculty and staff trying to make ends meet in a very expensive Washington, D.C.

The reality a new president will face, then, is a university in a financial predicament with the only solution that of increasing revenue from enrollments, particularly undergrad enrollments — enrollments that struggle now despite an 82% admission rate. It won't be easy.

Demographic trough

Part of the problem is demographic. College enrollments across the country are bottoming out in a long demographic trough because of America's declining birth rate after the Great Recession. CUA's trough, though, looks deeper.

Vincentian Fr. David M. O'Connell, Catholic University of America president 1998-2010, is seen in this 2008 file photo. He was named coadjutor bishop of Trenton, N.J., in 2010. (CNS photo/Bob Roller)

Its traditional undergraduate student base has been parochially educated, white, middle-to-upper income, suburban Catholics from the Northeast. That particular demographic group is declining much more sharply than the general population of 18- to 25-year-olds. Competition for students in CUA's niche will be fierce, not just from its traditional Catholic university competition like Villanova and Seton Hall, but now equally from student-hungry secular universities in the East as well.

CUA's approach to the enrollment problem under both recent presidents has been to distinguish itself with a relatively narrow "Catholic" brand. It promoted itself as a university that was THE Catholic University of America, with the unstated implication that CUA was more officially Catholic and more orthodox than the competition, an approach that made the perennial question of Catholic identity an existential one for the university.

Some might question the approach O’Connell and Garvey took. While the university does have world-class Catholic-related programs in theology, church history and canon law, it also has terrific programs in the arts, the humanities and the social sciences. Its physics department is outstanding. Its schools of nursing and social work are among the best in the nation.

Some other U.S. Catholic universities have done a better job than CUA in attracting students and building faculties and advancing research by nudging Catholic identity into a largely inspirational or supporting role behind a more secular academic mission.

CUA cannot do that. Its founding, its history, its pontifical status, its de jure relationship with the bishops of the United States, and even its name make clear what its mission as a university must be about. Arguably, the church in the United States needs CUA to be precisely this. But how the university answers its Catholic identity question — there's the rub.

People in Washington, D.C., walk near the campus of The Catholic University of America Nov. 24, 2020. (CNS/Tyler Orsburn)

Catholic identity

In the United States a worrisome understanding of Catholic identity is ascendant in some quarters that begins with the notion that our faith is under assault from the disorienting social and cultural changes taking place in modern life. In this understanding, Catholics see themselves as victims of a host of faceless entities and -isms.

If a lame metaphor might be forgiven, the upshot of emphasizing victimization is a Catholicism that circles its wagons in defensiveness. Vis-à-vis the modern world beyond the wagons, that defensiveness limits responses to either militant confrontation or hiding behind the wagons to guard the purity of the faithful. And even those faithful cloistered within the circle of wagons must continually be surveilled for purity.

No doubt theologians have better labels to name this worrisome understanding of Catholic identity but, arguably, the public controversies surrounding CUA in recent years (from speaker policies to the recent law school icon debacle) have had a whiff of it. In the few corners of CUA where opposition to the papacy of Pope Francis has grown, it is more than a whiff.

Such thinking contradicts the nature of a university. It's contrary to the spirit of St. Pope John Paul II's magisterial work on the purpose of a Catholic university, Ex Corde Ecclesiae, and to Cardinal John Henry Newman's canonical The Idea of a University. It's profoundly at odds with the evangelization at the heart of the papacy of Pope Francis — his papacy's openness to the world, accompaniment of all sinners, humble listening, mercy and synodality.

A Catholic university that understands its identity in this clenched, defensive fashion cannot last, much less grow.

More to the immediate point, a Catholic university that understands its identity in this clenched, defensive fashion cannot last, much less grow. Far from broadening the student base, if CUA continues to adopt such an understanding of its identity, few students — few Catholic students — will find it welcoming and even the mere whiffs of its current presence on campus alienate many prospective applicants.

Much more could be said about what's needed from a new president at CUA. The student base needs to be broadened to reflect the increasingly shrinking white Catholic population in the United States, with outreach and programs attractive to burgeoning first- and second-generation immigrants from Africa, Asia and especially Latin America. Likewise, greater efforts might be made to reach out to working-class populations and those outside the parochial school pipelines (although homeschoolers seem over-represented at CUA). Non-Catholic applicants must feel welcomed and not marginalized.

To address faculty morale, the president should be a genuine scholar who truly values the vocation of the professoriat, enjoys the life of the mind, empowers the faculty and is supportive of the research mission of the university. The new president might also reconsider President Garvey's division of the board of trustees, which segregated its bishops from its lay trustees. Synodality has proved to be more pragmatic than hierarchy.

As at any university, this is not a job for an ideologue. University presidents must be pragmatic bridge builders able to work across the academic divisions and ideological polarization that divide American campuses today.

Critically for CUA, what's also needed is a president who is severely allergic to "circle the wagons," defensive Catholicism. It needs a president who, in the spirit of Pope Francis, engages the world beyond the university walls not with fear, judgment, confrontation and retreat, but with joy, accompaniment, humility and hope in the advancement of truth.