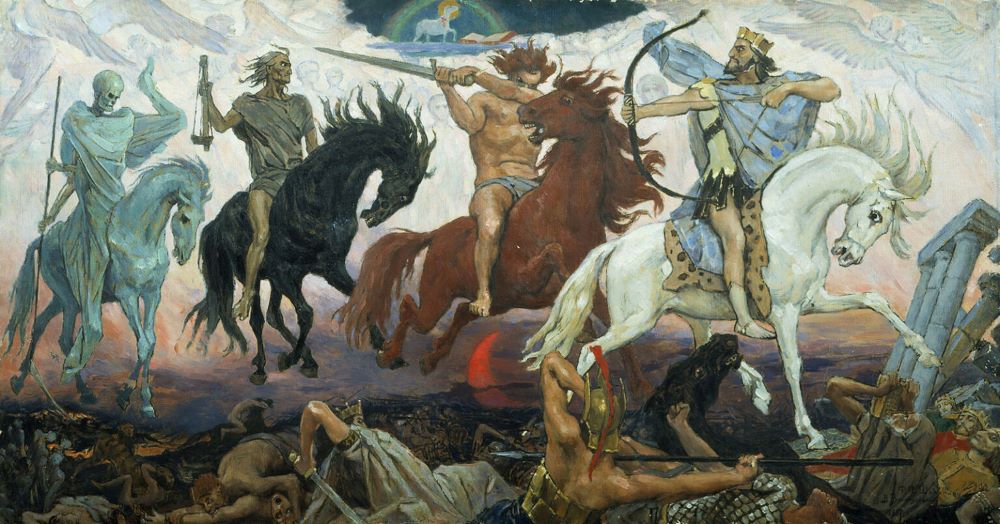

"Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse" by Viktor Vasnetsov, 1887 (Wikimedia/Creative Commons)

The apocalyptic Scripture passages at the end of the liturgical year tell us humanity is capable of screwing it up so badly only God can save us.

I like science fiction, with its stories of amazing technology and encounters with alien civilizations. These stories are fun because they take me out of the real world into a world of fantasy.

But if there is one science fiction genre that I hate, it is apocalyptic stories of dystopian futures after a nuclear war, plague or environmental disaster. I hate these stories because they are too close to a future that could happen to humanity. They are too much like what I see in the news every day.

There is war in Ukraine and Gaza. Putin is threatening nuclear war in Europe. Iran and Israel are at loggerheads. Dictatorships abound in Africa and Asia. Criminal gangs, civil wars, terrorism and famine plague the world. The weather is giving us either droughts or floods. And scientists are warning us that global warming is advancing closer to disastrous tipping points that will impact the planet for thousands of years.

In such a world it is no wonder we turn to fantasy or to the Hallmark Channel or to shows where the good guys beat up the bad guys in 90 minutes or less.

Today we need to see that our political vocation is to work for justice and reconciliation as Jesus did. This will not be easy.

The Scripture readings at the end of the liturgical year are the biblical equivalent of dystopian science fiction. In Catholic churches the last Sunday of the liturgical year (Nov. 24 this year) is the feast of Christ the King, which reminds us Christ is not only spiritually supreme but also politically supreme. Next Sunday (Dec. 1), the new liturgical year begins with Advent.

The apocalyptic Scripture passages at the end of the liturgical year tell us humanity is capable of screwing it up so badly only God can save us.

Such thoughts can lead us to despair, to give up and do nothing. I confess to being tempted to despair.

But as Christians we believe Christ did not just come to save us. He came to call us to join him in working for the establishment of his Father's kingdom, his Father's reign. We are called to continue his mission on earth, not just wait passively to join him in heaven.

If it is God's reign we work for, we must see all humans as our brothers and sisters, citizens of God's kingdom. We must see the earth as God's gift that must be treasured and protected.

If Christ is king, politics is not just about self-interest and power. Politics is about the common good, it is about justice. It is about the community acting together to help the less fortunate and to foster peaceful relations among people. It is about protecting God's creation for future generations.

The early Christians hoped Jesus would come soon, slay their enemies and establish his kingdom. For many centuries, too many Christians felt it was their job to slay their enemies and establish God's kingdom with the sword. But Jesus never took up the sword.

Today we need to see that our political vocation is to work for justice and reconciliation as Jesus did. This will not be easy. After all, Jesus failed and was crucified. But if we want to follow Jesus, this is the only way we can go. Jesus' way was vindicated by the Father who raised him up and placed him at his right hand as king of the universe.

At the end of the liturgical year and the beginning of Advent, we profess our faith that "Christ will come again." Optimists believe that by working together we can make the world a better place so Christ's coming will be sooner.

Pessimists believe we humans will screw things up so badly that Christ will have to come to save us. Only history will tell us who is correct, but it is clear from the Gospels that Christ calls us to follow in his footsteps by living lives of love, struggling for justice and working for peace. This is our vocation as Christians. This is what politics should be about.

Advertisement