A woman wearing a mask for protection from the coronavirus sits inside an empty metro train in Rome March 12. (CNS/Reuters/Remo Casilli)

"If you have a diary, keep writing it. If you don't have a diary, begin one. This is an extraordinary moment." This is what I told my undergraduate students at the beginning of our last non-virtual, in-person class March 11, just before the five-week break decided by Villanova University.

This is an extraordinary moment for the world as well as for the church. In some sense, it is truly unprecedented for the impact it is having on religious life, not only on the Catholic Church. On March 12 the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints decided to cancel all meetings worldwide.

In this moment of life-and-death health crisis, the perception can be of the final blow struck against a religious tradition already in decline, an emergency used opportunistically by secular and political authorities to forever marginalize religion exactly when it is needed the most. But this would be a self-serving and ideological analysis.

Observing what has happened to Italy in the last two weeks and what is happening in many areas of the U.S., one cannot fail to take notice of the state of suspension of every public liturgical activity of the church. In Italy the prohibition to celebrate all Masses has come from the government, and has been accepted quickly and without hesitation by church authorities.

Some important Italian Catholic progressive intellectuals wrote in op-eds that the bishops accepted it too quickly. But that was in an early stage of this emergency: there is a consensus both in the Italian church and in the Vatican that these draconian measures are absolutely necessary. But Italy has lived since 1945 in a quiet entente between church and state. I am curious to see how this will play out in the U.S., given the very different historical and constitutional relations between church and state.

In many countries now the liturgy (in Greek: action of the people) is suspended for the sake of the people. This could last for weeks or months, into the Easter celebrations and possibly until the season of first Communions (our daughter is among those included) and Pentecost. There are examples of suspension of Masses in some plague-stricken areas in the past, but not yet many examples (like in Italy and now Malta) of nation-wide total bans of the celebration of Mass for weeks.

Advertisement

What does it mean for the community not to gather for Mass for some weeks? In the last few years, it has become evident the virtualization of the religious experience (on media and social media) at the expense of the truly sacramental in its physicality. The suspension of sacramentality entails a detachment from the 'stuffy' character of Catholicism: the bells, the smells, all the works. It is a kind of liturgical fast.

The good thing is that this forced suspension of the participation to the liturgy of the church could make us feel the need for a de-virtualization. On the other hand, the danger is that the tension created by this deep and prolonged scare is endangering social connections (with co-parishioners, with other parents at the Catholic school, with neighbors and colleagues) that are already frail and difficult to develop in normal times (this is something I noticed and continue to notice after 12 years in the United States).

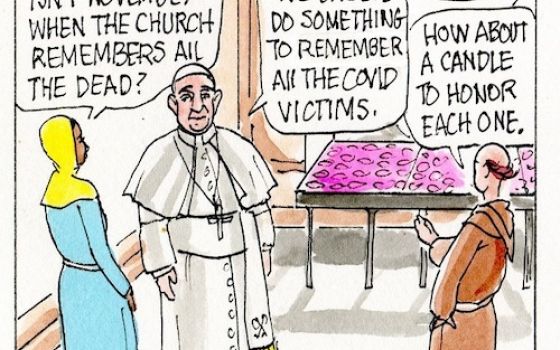

This suspension of the celebration of the Mass could also have ecclesiological consequences, that is, on the way Catholics conceive and imagine the church. The pope being the only one celebrating Mass in public in Italy every day (via internet from the chapel in the residence of Santa Marta) is elevating the papacy to levels that not even the Ultramontanist majority at Vatican I, the council that declared papal primacy and infallibility, could imagine.

A barber reads a newspaper in his empty shop in Rome March 10. (CNS photo/Paul Haring)

On the other hand, if you have watched it, you have noticed that it is a down-to-earth Mass, in Italian, in the rite of Vatican II (not the Latin pre-Vatican II Mass), and very much like the average weekday Mass with its sparse congregation, the sometimes truly bad singing, without the script and theatricality of papal masses in St. Peter's or during apostolic trips. It is, in its own unintentional way, a contribution to the debate (stronger in the English-speaking world than anywhere else) on the liturgical reform of Vatican II and the wishes for a neo-traditionalist "reform of the reform."

But I have to confess: I hope that once this emergency passes, the broadcast of the daily celebration of the Mass by Francis will not continue, or that it will become superfluous. In a synodal church that tries to become more missionary by being all-ministerial, the identification of the pope as "celebrant-in-chief" could have long-term side effects contrary to Francis' vision for the future of the church.

Evangelii Gaudium 'to the extreme'

Rome's churches were ordered closed by the papal vicar for the Rome diocese March 12. But the order was modified March 13, to allow pastors to open their churches, if they did so with care to limit people's contact with one another.

It remains to be seen how this reversal will affect the Italian bishops' conference's recommendation that individual bishops order the closure of all churches in Italy until at least March 25. (Some regional bishops' conferences, like Lombardy, had not accepted that recommendation.)

A delivery driver transfers groceries from a shopping cart to a motorbike outside a supermarket in Rome March 11. (CNS photo/Paul Haring)

This situation is in some sense taking to an extreme Francis' invitation to the church, since his first major document, November 2013's Evangelii Gaudium, to "go forth" and leave the comfort zone of the sacristy behind. Francis' "field hospital" church now has to support the literal field-hospital, war-like situation that some hospitals in Northern Italy, among the best in the world, are facing.

This situation is putting some Catholics off-balance: those who want to play catacombs, to role-play the persecution during the Roman Empire and celebrate clandestine Masses in a rejection of the government decree as if it was motivated by anti-Catholic sentiment. As if the prime minister, Giuseppe Conte, were not a Catholic and also a devout follower of Padre Pio.

But this is creating some terminological difficulties also for those who continue to describe Masses celebrated without the assembly as "private Masses," when it is clear that every Mass is public by definition, whether the people is present or not.

This global health crisis, which is accelerating in some countries political and constitutional crises (in the U.S. especially), is forcing upon us hard rethinking of important concepts that have reshaped the theological conversation in the last few years.

What is the meaning of vulnerability and how different can it be in different countries and societies? Vulnerability is different, during a pandemic, between a country where there is a strong public health care system (like in Italy) and a country (like the U.S.) where the public health care system plays a supporting role to private, for-profit health care providers.

What does it mean to practice radical hospitality in the time of a pandemic? How true is that we see ourselves as one people of God if we don't measure everything we do against the needs of the weakest among us?

This crisis could be an opportunity to rediscover the wisdom of Catholic social doctrine, especially concerning universal access to health care as a fundamental right, but also the role of government regulations for the sake of the common good. We will see who among the episcopates and other Catholic leaders will be receptive to this challenge.

What is being forced upon them and us is something else. The first, most measurable effect of the crisis is the redrawing of the boundaries not only between persons, but also between church and state: in Italy for now, but soon in other countries affected by the virus. The debates of the last few years about liberalism and Catholic anti-liberalism are now moot or at least have aged very rapidly.\

It is not liberalism that has made some countries (like the U.S.) weaker than others in responding to this emergency by sidelining scientists and downplaying their role in advising political leaders. It is certainly not the anti-liberalism that we know that can put science in charge of giving advice to politicians.

A waiter wearing a mask for protection from the coronavirus serves a table at a restaurant near the Vatican in Rome March 11. (CNS photo/Paul Haring)

The real effect, measurable already in Italy, is the effect in terms of limits to religious liberty. In order to protect the elderly and the vulnerable, there are limits to the freedom of worship — and the state does not consider heroic your will to become a martyr of the coronavirus if you put other people's lives in danger by risking to spread the infection.

In cases of an emergency like this, it has become clear who is in charge (governments) and who is taking orders (the churches, among others). This is another episode in the history of biopolitics as the most important force behind the reshaping of the relations between church and state: the 20th century wars, the changes in sexual morality, the medicalization of all stages of life from conception to death, and the post-9/11 national security state. Now it's the turn of this global pandemic.

National governments are weaker than they used to be, but less weak than the churches. When it is about protecting the common good, national governments are the authority — or at least, they are expected to be, somewhat in vain. There are countries where the role of public authorities is still taken seriously. We will see what happens in Trump's U.S., where the collapse of the authority and credibility of political leaders is not entirely different from the collapse of trust in church leaders. It is a test for both of them. Catholics expect words of meaning that can offset the daily diet of lies and deception, especially in an election year.

But there is something that does not depend on the presidents, the prime ministers, or the bishops. This moment is also revealing some deep dimensions of the Christian faith.

The video this week of Cardinal Angelo Comastri, the vicar general of Vatican City, leading the prayer of the Angelus and the Holy Rosary with some faithful at the Altar of the Chair in St. Peter's Basilica struck me.

There was a Roman cardinal, all alone, standing before a very simple chair, with a few people sitting behind him, in a basilica as empty as never before: an icon of the moments of stark loneliness of the believer in the secular world, but always in the company of the faith and of other faithful, sparsely but ever present, somewhere congregated.

[Massimo Faggioli is a professor in the Department of Theology and Religious Studies at Villanova University.]