(Dreamstime/Thodonal)

We don't know the end stage of recent developments in artificial intelligence (AI), or even if there is one, but the trajectory at least is clear. The relationship between humans and society, culture and the global economy will be fundamentally altered. AI's development has raised many questions — both technical and philosophical. I would offer that a theological perspective is also in order.

Most of us know the story of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. They were tempted by the evil one with fruit from the tree of knowledge. (Spoiler alert: They take the fruit, even though God warned them that if they did, paradise would be lost.) Of course, the story is allegorical, but since Christians believe this act of hubris was the original sin, its relevance to new temptations with "forbidden" fruit is worth exploring.

Already we're being warned. More than 1,000 of the biggest names in the tech world, including Elon Musk, Steve Wozniak and others, have petitioned for a pause in development to assess the consequences of further advances. In a recent essay in Time, one of the founders in the field, Eliezer Yudkowsky, called for development to be shut down or "everyone will die." That gets your attention.

Yes, discovery and innovation often bring enormous benefits. It's just that humans have a mixed record at best when it comes to governing these instruments of change.

This is so much more than advanced search. This tool, with an unprecedented ability to simulate other "voices" and possessing unprecedented amounts of information, will thoroughly change the way we interact with each other, and how we form our own opinions and ideas.

The large potential for both good and evil flowing from this revolution is starting to become manifest. There is ample reason to doubt whether we are up to the challenge of wise use. Just think of the harms to society from the rapid growth of — and abuses on — social media platforms. With the widespread deployment of AI on these media, malicious manipulations of the truth are all but guaranteed.

Yes, discovery and innovation often bring enormous benefits. It's just that humans have a mixed record at best when it comes to governing these instruments of change.

When our metaphorical ancestors gained consciousness, and thus agency, their purpose was hardly all noble. Cain killed Abel, tribes warred incessantly, and the seeds of present-day nationalism were sown. An evolutionary scientist might posit that competition for survival almost always leads to internecine warfare. But they also observe that healthy competition has yielded desirable outcomes for society.

From a biblical perspective, our long history of conflict may have been preordained, once we rejected God's primacy and yielded to a lust for power. We believe that only providential disruption by the Incarnation offered redemption from original sin. That's the mystery of faith. This can be neither proven nor disproven, but it is our lasting hope.

Advertisement

It seems to be in our DNA to worship. The question has always been: Who or what gets worshipped? Power and wealth are the objects of veneration for most people, notwithstanding whatever faith they may profess. Now comes along a new ability, born of human knowledge and ingenuity, to achieve the object of our desire. It will transform our thinking and, perforce, our values.

The inflection point will be when artificial intelligence crosses over to general intelligence and achieves a simulated consciousness, a chimerical free will. Some experts in large language models (LLM), the mechanism of machine learning, insist that's impossible. But I am not so sure. And many of AI's developers aren't either. It could be an evolutionary phenomenon.

The great Jesuit paleontologist Fr. Pierre Teilhard de Chardin believed that the next stage of human evolution was toward the "noosphere," a kind of melding of wisdom and being in the mystical body of Christ. He described our present stage of evolution as the "biosphere," inaugurated with the dawn of plant and animal life. In his vision, over the long arc of creation, we would continue to evolve through the noosphere to the culmination of existence — the omega point — with all things in Christ at the end of time.

Teilhard's conception represented a novel interpretation of Christology as well as evolution. For this, he faced opprobrium and was silenced by the Holy Office, the successor to the Inquisition. He was repeatedly banned from teaching and publishing his ideas, which are summarized in his masterwork, The Phenomenon of Man. He died in 1955 shortly after he completed writing the book.

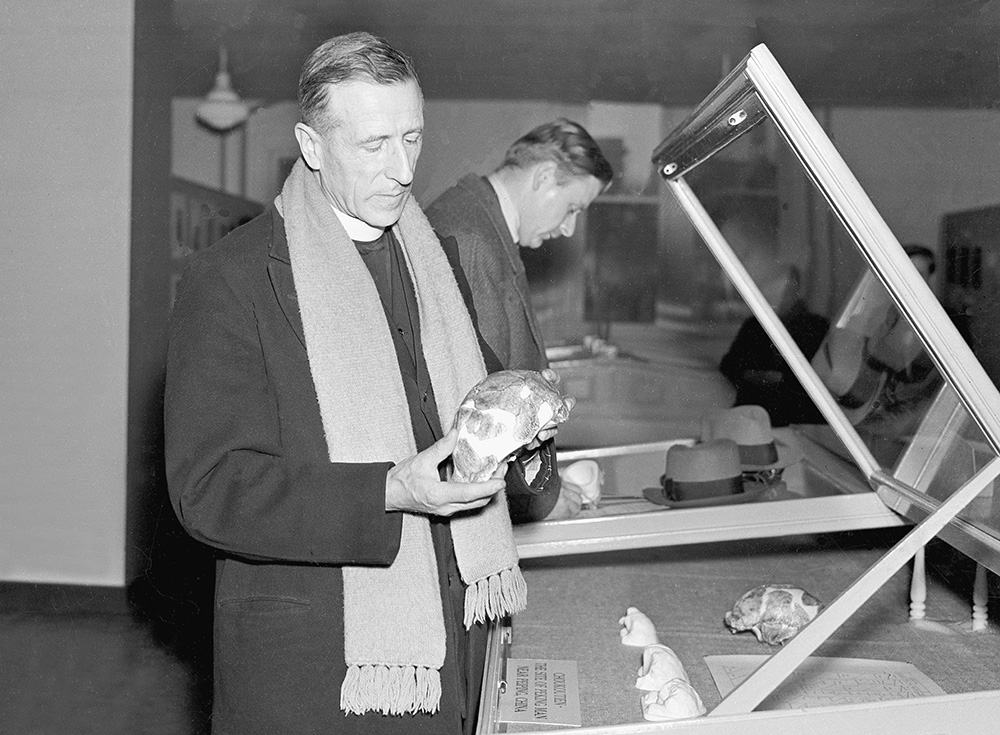

Jesuit Fr. Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, at the Symposium on Early Man at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia on March 18, 1937, holds the skull of a Peking man he found in Beijing. (AP Photo)

As late as 1962, the Vatican censored his ideas and forbade them an imprimatur. But in recent years, Pope Benedict XVI and Pope Francis have been more approving of his scholarship and have praised his work.

One wonders if he may have been prescient. Teilhard de Chardin was a Darwinist and a theologian. He thought there was no reason to believe that human evolution would stop with us.

He has been gone almost 70 years. Despite many challenges, there is evidence that our species is more socially advanced today than even a century ago. Is it possible that AI is a deus ex machina to take humanity to the next stage of a divinely ordained path of evolution?

One can't be certain how Teilhard would view AI, but as a paleontologist, he likely would not be surprised by its potential. Humanity has always evolved in response to the introduction of new elements in our environment.

Perhaps we are not confronting humanity's extinction, but rather the possibility of extending creation to a higher realm. It was choice, after all, that led us out of Eden. We may have a better, wiser choice within our grasp.

This is how destiny is written. The next few years will be an existential test of our humanity and our belief in a transcendent order. I don't think we have the option of stopping it.