Election worker Ramona Ortiz places a sign outside a polling station at a fire station in El Paso, Texas, just before polls open on Nov. 8, 2022. (AP/LM Otero, File)

Our political discourse is replete with myths that are often riddled with meaningless and baseless claims with little or no foundation in truth. Two of the more recent myths espoused by many U.S. political voices are that Latinos are either leaving the Democratic party in droves, or that Latino independent voters are voting for Republican candidates in overwhelming numbers. Such myths must be debunked — though with some nuance.

What has driven the myth of a supposed widespread Latino "defection" was largely exit polling during the 2020 presidential election. Some of these exit polls showed heavy swings in traditional Democratic-leaning Latino areas, leading some observers to speak of a realignment in Latino politics in America.

While this specific myth is occasionally true (like in Miami-Dade County, Florida, a geographic area with a large number of Latino Democratic voters), the larger truth is that several state-by-state analyses and studies undertaken by credible entities, like Equis Research and the UCLA Latino Policy Initiative, have demonstrated that Latinos did, in fact, overwhelmingly vote for now-President Joe Biden, with Biden beating Trump in some key states by a margin of three to one.

Employees process vote-by-mail ballots for the midterm election at the Miami-Dade County Elections Department Nov. 8, 2022, in Miami. (AP/Lynne Sladky, File)

What drives the discrepancies that exist between exit polling data and the Equis and UCLA type of studies are that the former tends to rely on samples that do not contain sufficient Latino voter responses, making the data wholly unreliable, while the latter studies the actual election results, with the use of ethnic modeling data from state voter files.

In short, the types of analyses that Equis and UCLA undertake are more accurate and prove that the notion of a Latino defection is an idea largely blown out of proportion by the mainstream press and others whose own agendas drive such false narratives.

The 2022 midterm elections continue to feed the falsehood of the Latino defection myth. Preliminary results indicate that in Arizona, Latino support for the Democratic (and incumbent) Senate candidate, Mark Kelly, remained steady in the high 70% mark. Republicans did not improve on Trump's 2020 performance in high Latino precincts. In Nevada, Latinos proved to be a key bloc in Democratic Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto's reelection efforts. She received almost 70% of the Latino vote. Both Arizona and Nevada were critical for Democrats in their battle to retain control of the Senate, and Latinos delivered for them.

A supporter on horseback has a sign for Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto, D-Nevada, at a horse parade to get out the vote Nov. 5, 2022, in Las Vegas. (AP/John Locher)

In Pennsylvania, Latinos voted for Democratic candidates for governor and Senate in large numbers, giving them close to 80% of their support. Democratic candidates in Wisconsin also received the lion's share of the Latino vote.

Interestingly enough, in South Texas, a place where we did observe a certain swing among Latinos moving from solidly Democrat to support for Donald Trump and other Republicans in 2020, this time we saw no gains for Republicans. Latinos supported Beto O'Rourke in higher numbers than they supported Republican Gov. Greg Abbott, and the three Republican candidates for Congress lost their races handily.

These numbers notwithstanding, there are indeed some locations where Latinos have trended more Republican, and this is where the debunking of the myth of a Latino defection requires some nuance. The most obvious such place is Florida, and more specifically Miami-Dade County. The realities of Latino voting patterns in Florida prove that the notion of a single Latino vote is quite complex.

Much has been said about the non-homogeneity of Latinos, and that is certainly true. Latinos come from a variety of Latin American countries, with differences in culture, linguistic accents and histories.

Advertisement

These differences are also evident in the variety of voting behaviors of Latinos, voting patterns that are driven by a variety of ideological positions. And it is my contention that, contrary to the conventional thinking of many political scientists and other political observers, these ideological differences are largely driven by religious leanings, not economic ones.

Yet, even when it comes to the influence of religious ideology on political behavior, differences do exist between Latino Catholics and Latino evangelicals. I have argued elsewhere that Latino evangelicals have mimicked the theology and politics of white evangelicals, embracing "the often intertwined cultural and political idiosyncrasies of their White counterparts, as we saw most recently in their support of conspiracy theories behind the COVID-19 pandemic and their ridiculing of states' mask policies."

The rise of Latino evangelicalism in the U.S. has come with an increase in a more rigid conservatism. Though the conservatism of the evangelical variant of Latino Protestantism has existed for some time, the increasing population and thus spread of conservatism is also resulting in more conservative Latino political and electoral behavior.

By contrast, Latino Catholics have taken a different political posture.

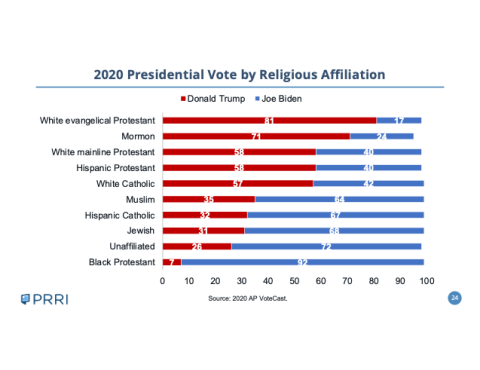

Robert Jones from the Public Religion Research Institute told me that he found that 58% of Latino evangelicals (classified as "Hispanic Protestants") voted for Donald Trump in 2020, whereas 67% of Latino Catholics voted for Joe Biden.

Even on myriad social issues, the differences between Latino Catholics and Latino evangelicals are quite stark. According to Pew Research, 70% of Latino evangelicals believe abortion should be illegal, while 54% of Latino Catholics subscribe to the same belief; and 66% of Latino evangelicals oppose same-sex marriages, while only 30% of Latino Catholics oppose them.

Hence, it may be safe to assume that in many ways what has driven the move from Democrat to Republican among some Latino voters is largely Latino evangelicals rather than Latino Catholics.

Again, let's look at Florida. A majority of Latino voters there voted for the Republican candidates, Gov. Ron DeSantis and Sen. Marco Rubio. Carlos Odio from Equis Research has observed that this is the first time since 2006 that Republicans have won a majority of the Latino vote in the Sunshine State.

Yet, again, the Florida context points to the diversity within Latino communities. Republican candidates won by large margins in heavy Cuban precincts. Outside of Cuban-majority precincts, Republicans did not fare as well, losing most of Latino-majority precincts in counties in the Central Florida area, which now have a high number of Puerto Rican voters. Yet Odio observes that even these counties have experienced a decline in Democratic support.

Clearly, there is no one-size-fits-all reality to understanding the Latino vote.

My hunch is that Latinos themselves have intentionally not debunked this myth of Latinos as a monolithic swing vote. Part of this resistance may come from a place of defiant self-importance — something Latinos have had to grab for themselves, for others have ignored their plight for so long.

Partly for this reason, early political figures like the Mexican Edward Roybal and the Puerto Rican Herman Badillo joined forces to create the notion of a uniform Latino vote. They realized that despite the variety that exists among Latin Americans in the U.S., much united them. This also made practical political sense, as both leaders saw the potential to obtain long-denied power for their people through the concept of a pan-Latino identity.

This mission to create a sense of a pan-Latino reality was in some ways a rallying cry that declared that Latinos were el futuro (the future). The increase in Latin American descendants in the U.S. could not be ignored, though for all practical purposes it was. Roybal's and Badillo's efforts would not produce the fruits they hoped to see, but the demand for respect had been made.

In some ways, the denial of this myth-debunking is also a rallying cry of sorts. It is the cry of Latinos that we are no longer el futuro, but rather estamos aquí (we are here). While Roybal's and Badillo's fight was one for recognition, the rallying cry today is one for respect.

It is undeniable that both national parties, but perhaps more so the Democratic party — a party to which Latinos have largely remained faithful — have taken them for granted. This unfortunate reality can be seen in several ways, from lack of investment in Latino communities to the denial of proper Latino political representation.

Could it be the idea of Latinos as a quintessential swing voting bloc is a myth they themselves prefer not to debunk so that national political parties finally take their plight (and vote) seriously, as well as their clamor for proper representation?