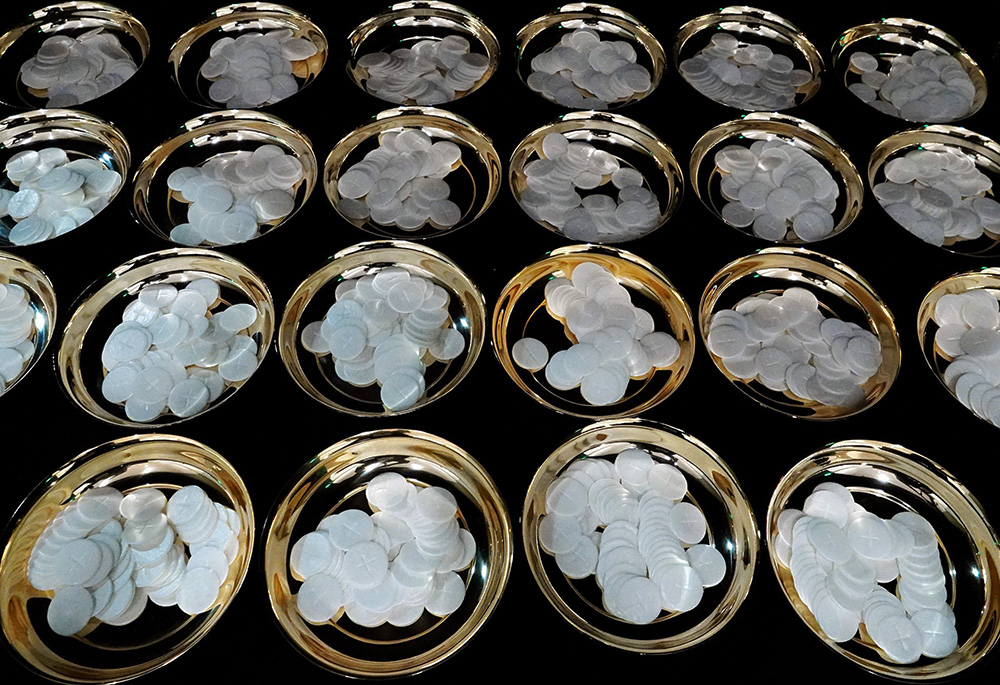

Altar bread is seen on patens before Mass Oct. 8, 2021, at the Renasant Convention Center in Memphis, Tennessee, during the diocesan eucharistic congress. (CNS/Karen Pulfer Focht)

The U.S. bishops have initiated a National Eucharistic Revival, beginning with the 2022 feast of Corpus Christi and concluding on the 2025 feast of Pentecost. A key moment in the revival is a scheduled National Eucharistic Congress for July 2024 in Indianapolis.

A rededication of the Eucharist is crucial, for anything that is repeated weekly, or daily for some, can become rote with an accompanying loss of meaning.

The Eucharist, the source and summit of Catholic spiritual life, is the most meaningful sacrament of the church. Before I became Catholic, I sang in the gospel choir in a Catholic church. Curious about why anyone would want to be Catholic, I asked one of my fellow baritone singers, "Why are you Catholic?" His answer, confusing then but clearer now, was, "It's all about the Eucharist."

Two years later I became Catholic, and thus began my still expanding grasp of the Eucharist. Twenty-four years after my confirmation, I relate to St. Teresa of Ávila's sentiment written 500 years ago: "Oh wealth of the poor, how wonderful can you sustain souls, revealing your great riches to them gradually and not permitting you to see them all at once! Since the time of that great vision, I have never seen such great majesty hidden in a thing so small as the host, without marveling at your great wisdom." Each reception of the Eucharist expands my vision, heart and vocation.

I therefore applaud the bishops' eucharistic revival. Yet, I am suspicious of the bishops' intent. These are many of the same people, after supporting a president (Donald Trump) whose racism and misogyny was appalling, immediately pounced on a Catholic president (Joe Biden) with threats of a eucharistic ban. In addition, recently San Francisco Archbishop Salvatore Cordileone ordered that House Speaker Nancy Pelosi be forbidden from receiving the Eucharist. Cordileone's letter notes:

I am hereby notifying you that you are not to present yourself for Holy Communion and, should you do so, you are not to be admitted to Holy Communion, until such time as you publicly repudiate your advocacy for the legitimacy of abortion and confess and receive absolution of this grave sin in the sacrament of Penance.

Advertisement

I am Catholic, I do not "believe" in abortion, but I believe we should work to construct a society where abortions are unnecessary, not illegal. I also believe our society's approach toward abortion reflects a male-centric lack of compassion for women. I believe that as one person has said to me, "If men got pregnant, abortions would be as accessible as an ATM." It is sobering that the states that have banned or are most likely to ban abortion are also those with the flimsiest safety net for women and children. Our inordinate focus on making abortions illegal clouds our vision of the broader social and economic conditions that diminish life for women and children.

The bishops' focus on abortion confirms the perspective that issues related to sex and gender are the only sins of consequence. Divorce? No Eucharist. Abortion? No Eucharist. Yet, on racism, white supremacy, white nationalism, homophobia, anti-immigration, support for capital punishment, support for mass incarceration, support for policies that create poverty while 1% are enriched, support for assault weapon proliferation, support for unjustified invasions, support for a president whose racism and lies created incalculable harm — the bishops seem to say, "Happy are those called to the supper of the Lamb."

Fortunately, misappropriations of the Eucharist cannot dilute its power. This liturgical year I attended an Advent retreat led by Fr. Peter Bosque, a retired priest of the Diocese of San Diego. He reminded us that, as St. Augustine said, in the Eucharist we are placing ourselves on the altar. Augustine's sentiment echoes that of Romans 12:1-2: "I appeal to you therefore, my brothers and sisters, by the mercies of God, to present your bodies a living sacrifice." Following this prayer is a discussion of how our varied gifts come together as we become, the body of Christ. Thus, "your bodies" is not about individuals, but the collective.

Bosque also noted that "Mass is not a duty done but a love embraced." He further noted the Liturgy of the Eucharist is not about what we receive, but what we become. He emphasized that the Eucharist reaffirms, strengthens, illuminates and expresses the fact that we become, and already are, the body of Christ.

In this 2002 file photo, a woman receives Communion during a special Mass marking the first Eucharistic Congress of the Knights of Columbus at the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington. On June 16, 2022, the feast of Corpus Christi, the U.S. bishops' three-year eucharistic revival begins. It culminates with a eucharistic congress in 2024 in Indianapolis. (CNS photo by Andy Carruthers, Catholic Standard)

The Eucharist is not magic. The Eucharist is our realization that Christ was broken for our wholeness. And the "our" is not for individual benefit, but that we come together with our brothers and sisters to form and live as the body of Christ on earth. Thus, like Christ, we are broken and given for the life of the world. The Eucharistic Prayer book "Bread of Life" contains the following by Oblate Fr. Ron Rolheiser: "More so than the bread and wine, we, the people, are meant to be changed, to be transubstantiated. The Eucharist, as sacrifice, asks us to become the bread of brokenness and the chalice of vulnerability."

Further, Eucharistic Prayer 4 petitions God "to make of us an eternal offering to you … that we might live no longer for ourselves … but for him … to complete his work on earth." This prayer illuminates what happens in the Eucharist. We are the offering, we live as Him, we together complete his work on earth. That work is not judgement, division or exclusion, but love, mercy and justice. Bosque reminded us that the Mass is not for us, "but for the world, and that it is food in our journey to become love."

I am hoping that our revival of the Eucharist is about us becoming the body of Christ, with all the accompanying beautiful implications. The Eucharist is not for the worthy, special, virtuous or qualified, nor is it a tool to affirm or deny a narrow political agenda. It is much more, it is our profound encounter with the incomprehensible love of God, an encounter that calls us to love in return. This love is not abstract, for it is specific enough to address the poor and excluded.

The Eucharist is not for the worthy, special, virtuous or qualified, nor is it a tool to affirm or deny a narrow political agenda. It is much more, it is our profound encounter with the incomprehensible love of God, an encounter that calls us to love in return.

I refer to Goffredo Boselli's The Spiritual Meaning of the Liturgy: School of Prayer, Source of Life, which includes the chapter "Liturgy and Love for the Poor."

In a detailed exposition of 1 Corinthians 11, Boselli explains that the divisions of the church at Corinth were because the wealthy gathered for sumptuous meals while the poor were excluded and went hungry. Thus, what scandalized the Eucharist in the church at Corinth was how the poor were cast aside. Boselli writes, "What was true of the community at Corinth is also true of Christian communities of today; not to share with one's poorest neighbors 'show[s] contempt for the church of God' (1 Cor 11:22)."

He goes on to say, "In a culture marked by individualism, competition, affirmation of oneself at all costs even at the expense of others and against others, it is difficult to be church, to truly be a community. Only from the Eucharist, from the prophetic gesture of the breaking of the bread, can the Christian communities of the West renew their awareness that the church cannot be the body of Christ where Christians fail to turn away from egoism and refuse to share their goods with the poor."

Boselli also notes how the Didache, the ancient document also known as the "Teaching of the Twelve Apostles," helps us understand their views of the Eucharist. In the Didache, the word for Eucharist was klasma, or, simply, "broken." Imagine if we substituted Eucharist for "broken"? Jesus "broken" that we might live, we "broken" that others might live, we "broken" to become part of the one body of Christ.

The Eucharist has riches that can never be exhausted. It empowers an individual so molded into Christ that, "not I live, but Christ lives in me." It also recreates a diverse, fragmented, flawed community of believers into a loving justice-building body of Christ in the world.

Jesus said two things about the future in the Gospel of John: First, we will do greater works than he did; and second, that he has many more things to tell us. The Eucharist fulfills those promises. I am hopeful the eucharistic revival will be an opportunity to grasp and live into the love and community made possible by our sharing this sacred mystery.