A delivery man bikes with a food bag from Grubhub on April 21, 2021, in New York. Uber Eats, DoorDash and Grubhub sued New York City on July 6, 2023, to block its new minimum pay rules for food delivery workers. (AP/Mark Lennihan, File)

The summer of 2023 has been electric for the labor movement. Unofficially dubbed "hot strike summer," workers from janitors to UPS drivers to Hollywood actors have threatened or engaged in work stoppages at rates not seen since the 1980s, with the support of a majority of Americans.

Buried in the midst of high-profile labor negotiations was a major labor victory by less-heralded members of the entertainment industry that will likely impact a large swath of the labor market.

In June, the National Labor Relations Review Board (NLRB), the federal agency charged with protecting the rights of workers to organize, issued a ruling in favor of the makeup artists, hair stylists and wig artists who provide services for the Atlanta Opera. The subsequent rules change could make it easier for millions of American workers to organize, unionize and strike to protect their shared interests. The ruling broadened the conditions a company had to meet to classify a worker as an independent contractor rather than an employee.

This is a hopeful outcome for Catholics who are invested in the church's 130 years of support of organized labor at a time when union activity across sectors is at its highest in decades, after a long decline.

Social cohesion is founded not just on identity, but in the pursuit of perceived shared interests as well. Inclusive labor unions can do that.

The change is also a welcome victory for all working-class people who increasingly rely on the gig economy to make ends meet because, historically, as union membership falls, income inequality increases.

In McKinsey's latest American Opportunity Survey, 36% of respondents identified as independent workers. Extrapolated onto the workforce as a whole, this would account for more than 56 million people. In addition to saving on payroll taxes, employers who employ independent contractors also save on direct employee benefits such as health insurance and retirement benefits.

The newest development of the last decade is how much of this work is mediated and controlled by tech companies and their platforms.

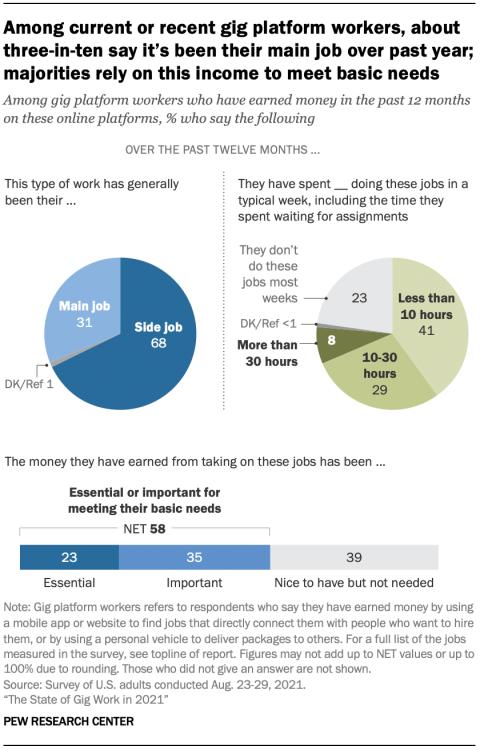

While tech companies frame their platforms as neutral arenas where workers can be their own bosses in their side hustles, the scope of the gig economy no longer matches this, if it ever did. According to a Pew Research Center report, 16% of Americans have performed gig work through an online platform. The numbers are higher for workers who are younger than 30 (30%), Hispanic (30%) or the lowest wage earners (25%).

The working poor, then, are increasingly compelled to supplement their unlivable wages with greater workloads and fewer regulatory protections. Indeed, nearly a third of the Pew respondents said these platforms provided their main source of income, and a majority said they rely on them to make ends meet.

The growth of both gig work and worker dependence on the sector cry out for increased protections for everyday people. This is especially true because these companies exercise a great deal of control over the rate — the government's primary standard for determining whether one is a contractor or employee.

Rideshare drivers, for instance, find that their pay or even their opportunities to pick up customers is dictated by the extent to which they follow the orders of the algorithm, their digital middle manager. What's worse, because the algorithms are proprietary technology, drivers cannot even get complete answers to why they must do something or why there are changes to pay.

Workers on these platforms walk like employees, talk like employees, but have the protections of contractors.

Given trends in sectors like higher education, which has seen the consolidation of a two-tiered workforce defined by a massive underclass of contracted, overeducated and underpaid adjunct professors, it would be naive for other members of the educated professional class to assume that they are safe from these abuses. After all, the adjunctification of higher education took place before the broad pivot to artificial intelligence currently underway.

Since the publication of Pope Leo XIII's 1891 encyclical on labor, Rerum Novarum, the church has placed a special emphasis on the role of organized labor in a just society. The NLRB decision is a heartening sign from the standpoint of Catholic social teaching because it sets the table for an increase in a value central to the modern church: solidarity among workers.

Advertisement

Social cohesion — the sense of connectedness and solidarity among groups — is cultivated in response to something. It is founded not just on identity, but in the pursuit of perceived shared interests as well. Inclusive labor unions can do that.

This is one of the chief insights of Pope John Paul II's first encyclical on labor, Laborem Excercens, written to commemorate the 90th anniversary of Rerum Novarum. In it, John Paul develops his theory of solidarity as the fruit of the shared struggle of the working class and other oppressed people working together for the sake of the common good against the backdrop of unjust conditions.

He develops this idea, saying, "This solidarity must be present whenever it is called for by the social degradation of the subject of work, by exploitation of the workers, and by the growing areas of poverty and even hunger. The Church is firmly committed to this cause, for she considers it her mission, her service, a proof of her fidelity to Christ, so that she can truly be the 'Church of the poor.' "

The point of work, he insists, is to serve the good of human beings as a whole, not profit.

Workers and the church have a responsibility to organize and struggle to ensure that conditions reflect this fact. This NLRB decision, like victories in support of the rights of workers, is a win for us all because it is just.

The gig economy is the site of a crucial battle in the fight for workers' rights. Through their struggles for justice, workers fighting against unnecessary precarity will enrich our tradition. A part of that struggle that we can all contribute to is to make it easier for all workers to unionize, regardless of classification.